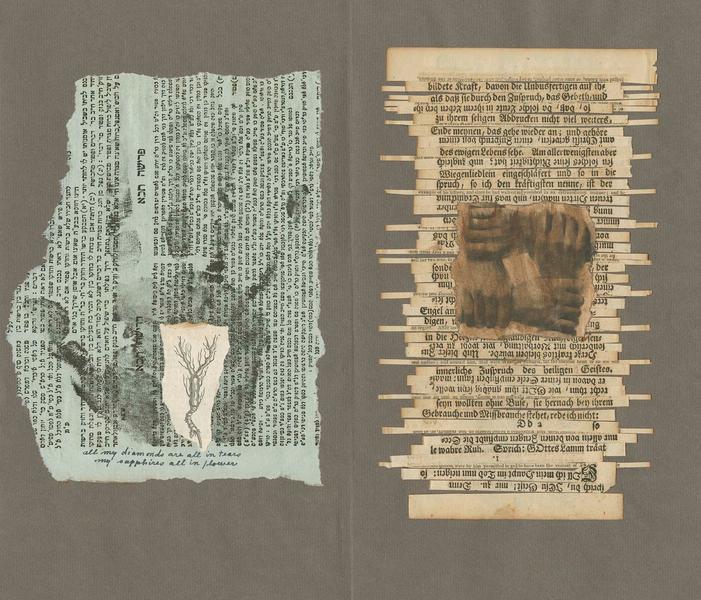

“Creation is a defiance of ordinary verbal communication. Its origins lie in the ineffable part of one’s own being and are much closer to the silence of the universe, than to its noises and verbalizations. Art is always just beyond language. Each work seems to be called up from a bottomless chaos and despite the magic order it finds in the artist’s creation, retains always the memory of the original chaos to which it is destined to return. The man of deep insight knows that authentic life is not lived arbitrarily but is governed by a secret mesh of invisible images.”[i]

An innovative artist who combined weaving and sculpture at a time when art and craft were thought to be mutually exclusive, Lenore Tawney was born Leonora Gallagher in 1907 in Loraine, Ohio. At age twenty, she left for Chicago, where she worked as a proofreader while taking classes at the Art Institute. In 1941, she married George Tawney, a young psychologist who died of an illness less than two years later. After this sudden loss, Tawney moved to Urbana and took classes at the University of Illinois. She returned to Chicago soon after and from 1946 to 1948 studied at the Chicago Institute of Design with Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and Marli Ehrman. After her studies, Tawney went to work as an assistant to sculptor Alexander Archipenko in Woodstock, New York, but found the studio atmosphere arduous. She returned to Chicago, bought a second-hand loom, and began weaving.

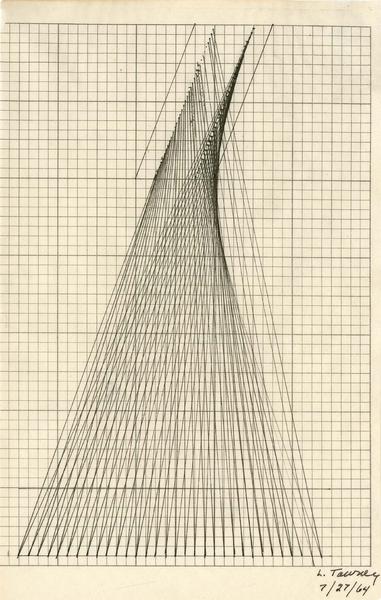

In the 1950s, Tawney focused almost exclusively on weaving. In 1954, she spent six weeks studying tapestry with Finnish weaver Martta Taipale at the Penland School of Crafts, North Carolina. She rapidly developed “a distinctive open-warp technique that was basically like drawing or painting with individual threads while leaving much of the fabric unwoven and transparent. Although the results found passionate admirers,” Holland Cotter explains, “Tawney’s work was considered heretical by orthodox craft adherents, but too ‘craftsy’ by the orthodox art world.”[ii] Despite this schism, Tawney found success as an artist. In 1957, the Chicago department store Marshall Field commissioned a work from her. “Tawney ended up creating two weavings—one that satisfied what she thought the company wanted and one that pleased herself. Marshall Field purchased both pieces.”[iii] Her career on the rise, Tawney left Chicago for New York, where she settled into a loft in a building on the Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan. While the loft lacked hot water, it offered sweeping views of New York Harbor, and the Coenties Slip was home to several artists at the time, including Ellsworth Kelly, Barnett Newman, and Agnes Martin, with whom Tawney developed a close friendship.

Calling her works “woven forms,” Tawney took weaving to the level of the monumental, the mythical, and the sculptural—where abstract expressionism had taken painting and sculpture. Unlike traditional tapestries that employed a rectangular format, were wall-mounted, and were often narrative, Tawney’s abstractions were of irregular shapes and “freely suspended in space. Often embellished with shells, beads, and fringes of feathers—and frequently composed of fibers of varying thickness and texture—[they] remained spiritually expressive, sculptural weavings.”[iv] In 1962, these woven forms were featured in a solo exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, and the following year, the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (later the American Craft Museum and now the Museum of Arts and Design) used her phrase for the title of a traveling exhibition, that included work by Tawney, Dorian Zachai, Claire Zeisler, Sheila Hicks, and Alice Adams.

![[un]common threads](/www_michaelrosenfeldart_com/uncommon_threads_install_34.jpg)