“Aesthetics is a very important part of the whole thing because, as I say, it is the language but it is also part of the means…I think aesthetics are something that absorb me only in the sense that I have to have the thing visually exciting to me, besides having it do something for me beyond the visual effect. In other words, the visual thing will attract me to it enormously and yet something will pull me into it, which is the thing itself. I am very strongly for form and matter, the combination of both.”[1]

Born in Alhabia, a city in Almería, Spain, to a family of seven children, Federico Castellon lived in Barcelona until 1921, when his parents moved the family to Flatbush, Brooklyn. Speaking little English, Castellon encountered difficulties when attempting to adapt to his new setting; he was often the subject of ridicule among his classmates due to his status as a foreigner, and his struggle to learn English resulted in him being held back in school for two years. Castellon turned to drawing as a coping mechanism, becoming consumed by the creative process for hours at a time. As a teenager he often visited museums in the city to observe the works of European Old Masters; he was not exposed to modern art until his art teacher at Erasmus Hall High School, who strongly encouraged his drawing practice, introduced him to the works of Cézanne and Picasso. Shortly after graduating, he completed a mural for the school that drew enough critical attention that it was exhibited in New York at Raymond and Raymond Galleries before being permanently installed in the school.

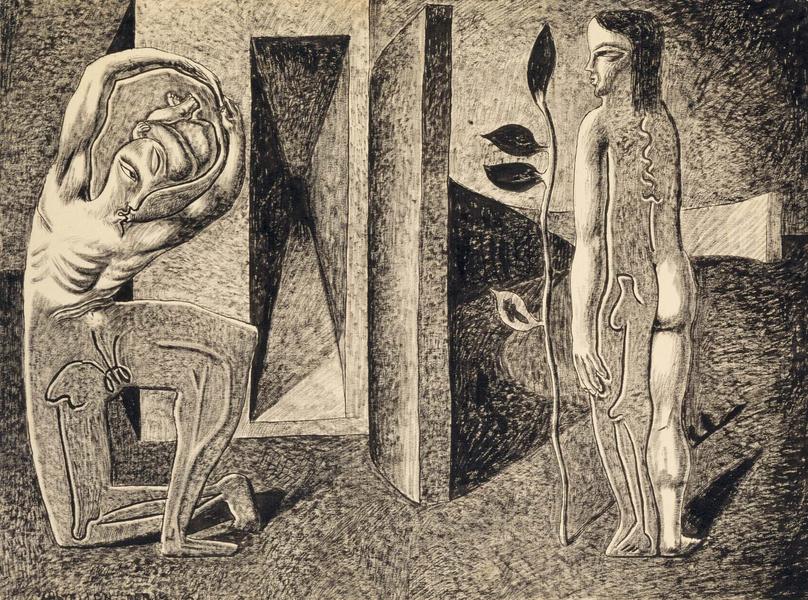

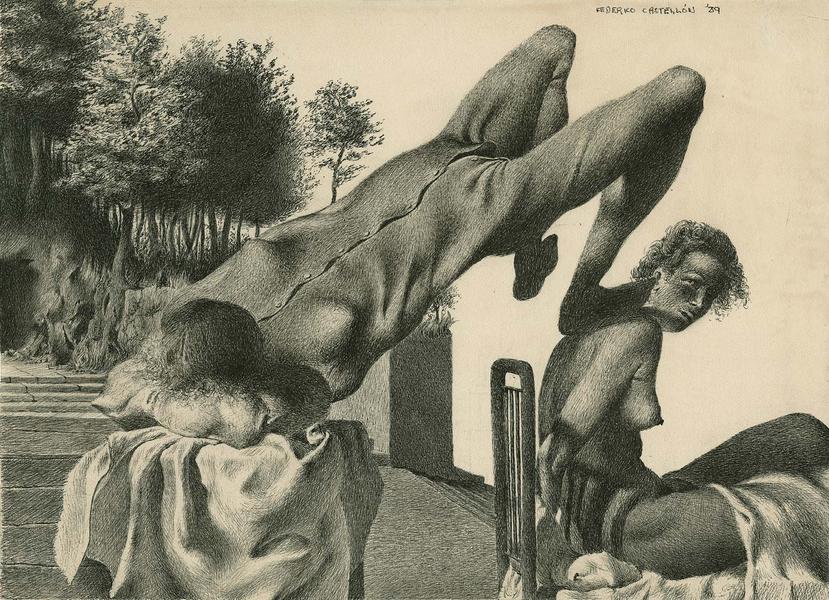

Though the Surrealist movement did not become widely known among American audiences until 1936, when the Museum of Modern Art opened Alfred Barr’s landmark exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism, Castellon had already cultivated a group of mature surrealistic drawings by the time he graduated high school in 1933. These works garnered the attention of Diego Rivera, to whom Castellon was introduced by a mutual friend when they attended a lecture the Mexican muralist gave on his (now destroyed) Man at the Crossroads murals in Rockefeller Center. Rivera took an immediate interest in Castellon’s work, bringing his drawings to the attention of the director of Weyhe Gallery in New York, who subsequently gave Castellon his first solo exhibition in late 1933, when the artist was only eighteen. Rivera was so impressed with Castellon that he also began writing letters to the Spanish Minister of Education on his behalf, persuading the Spanish Republic to award the young artist, who lacked the resources to attend college, a government fellowship to study art in Europe for four years. In 1934, Castellon left New York to study painting and printmaking in Paris and Madrid.

In Europe Castellon befriended many of the avant-gardists who made European cafés lively places for intellectual discussion while pursuing his artistic training. The artist’s return to Spain also caused forgotten memories from his childhood to resurface, an unexpected experience that would have a profound effect on his art. “I think the great moving thing was my revisiting Spain and awakening all sort of strange things that came up,” he recalled, “like finding I had a soul, because these memories became real all of a sudden… And my early days, my Surrealism was mostly, I felt, a kind of poetic mysticism…I always meant it as a kind of poetic mysticism.”[2] The uncertain relationship between dream, memory, and

[1] Oral history interview with Federico Castellon, 1971 April 7-14, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-federico-castellon-5452 (Accessed September 2021).

[2] Ibid.