“Man is like a light bulb. It can only get light through the little wire that connects it directly with the power plant. So it has to go within itself for light. Man, like the light bulb, is connected to the universal mind, cosmic consciousness or God – whatever you want to call it – and the only way he can get help or inspiration is by going within himself and drawing on this power. This is where artists, poets, composers and scientists get their ideas and inspiration. It is the source of all knowledge. You just have to go within, relax and let it flow through you.”[1]

The foremost sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance, Richmond Barthé (1901–1989) was born in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, the only child of Richmond and Clémentine Barthé. His father died within months of his birth, leaving his mother to support the family through her gifted needlework. Though he was uninterested in his schooling, Barthé was a voracious reader and developed an impressive, self-taught drawing talent at an early age. When he was sixteen years old, Barthé left home to work as a houseboy for a wealthy family in New Orleans, where he became interested in the Romantic and Neoclassical artwork they collected. In 1924, local acquaintances and his parish priest raised funding for Barthé to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. He excelled as a painter, taking classes with Charles Schroeder and studying privately with Archibald J. Motley, Jr. However, a series of portraiture exercises in clay prompted Barthé’s turn to sculpture and led to his first institutional recognition when the works were featured in the 1927 exhibition Negro in Art Week at The Art Institute of Chicago. In 1928, Barthé won a Rosenwald Fellowship and moved to New York City, where he continued his studies at the Art Students League. He settled in Harlem in 1929, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, where he entered an established scene of intellectual and creative social circles. Though he remained active in the social circles of Harlem, he moved his residence and studio to Greenwich Village a year later.

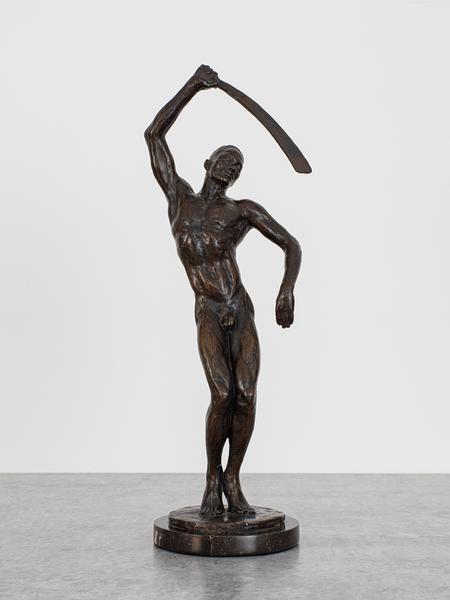

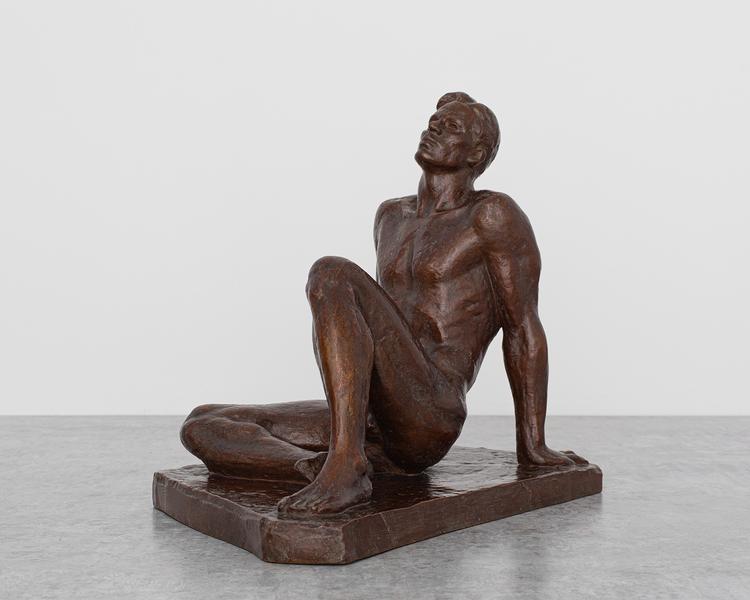

Barthé’s most important supporters and lifelong friends were the writer and philosopher Alain Locke and the poet Richard Bruce Nugent. He was also friends with poets Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, and Countee Cullen, cabaret performer Jimmie Daniels, playwright Harold Jackman, photographer Carl Van Vechten, writer and ballet impresario Lincoln Kirstein, and artists Paul Cadmus and Jared French. Although Barthé never publicly revealed his homosexuality, much of his artwork explores the political, racial, and homoerotic significance of the Black male nude. However, while this was prevailing focus of his oeuvre, Barthé applied his astute capacity for realism to the portrayal of a wide range of individuals throughout his career, including historical figures such as Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, Abraham Lincoln, and George Washington Carver; contemporary celebrities from the dance and theater world such as Rose McClendon, Harald Kreutzberg, Josephine Baker, and Paul Robeson; and archetypal, religious, and mythological subjects whose physical likeness were often inspired by people he encountered in his daily life.

Barthé enjoyed consistent recognition for his work following his move to New York City. In 1929, 1930, and 1931 the Harmon Foundation included his sculpture in their prestigious group exhibitions of works by leading Black artists. In 1931, the Caz-Delbo Gallery mounted a solo exhibition on the artist and, two years later, featured his work in a group exhibition alongside works by Picasso, Manet, Delacroix, Matisse, and Pissarro. In 1932, Barthé became the first Black artist to enter the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York when they acquired The Blackberry Woman (1932). The Whitney Barthé’s African Dancer (1933) in First Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors, and Prints the following year and the mounted a solo exhibition of his work in 1934. Barthé also received numerous public and private commissions throughout the decade, most notably Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho (1937–38), a frieze for the Harlem River Housing Project commissioned by the Works Progress Administration, and a monument to the journalist Arthur Brisbane commissioned by the city of New York and installed on the wall of Central Park in 1939. Barthé received Guggenheim Fellowships in 1940 and 1941, and in 1946 he was unanimously elected to membership in the National Sculpture Society. In 1942, Barthé and Jacob Lawrence became the first Black artists to enter the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, with the museum acquiring Barthé’s The Boxer (1942); in 1948, The Art Institute of Chicago also acquired a cast of The Boxer.

The fast pace of city life gradually took a toll on Barthé’s health, and in 1948 he bought a house in the parish of Saint Ann in Jamaica. The purchase was made possible by major commissions by President Estime of Haiti, who selected him to sculpt life-sized monuments to Toussaint L’Ouverture and General Jean Jacques Dessalines, which he completed in 1950 and 1952, respectively. He also accepted commissions from the Haitian government to design new coins in 1949 and 1953. Life in Jamaica afforded Barthé the peace he needed to recuperate his health; he continued to create new work which he sold to fellow expatriates. A local whom he hired for domestic help named Lucian Levers provided the inspiration for several of the male nudes Barthé sculpted in the early 1960s. In 1969, civil unrest in Jamaica prompted Barthé’s sudden move to Europe. He lived in Geneva, Switzerland, and Ibiza, Spain for a few months before making Florence, Italy, his new home for the next five years. His artistic production slowed during his time in Europe, and he enjoyed frequenting the city’s many cultural attractions.

[1] Richmond Barthé quoted in Samella Lewis, Barthé. His life in Art, (Los Angeles, CA: Unity Works 2009),13.