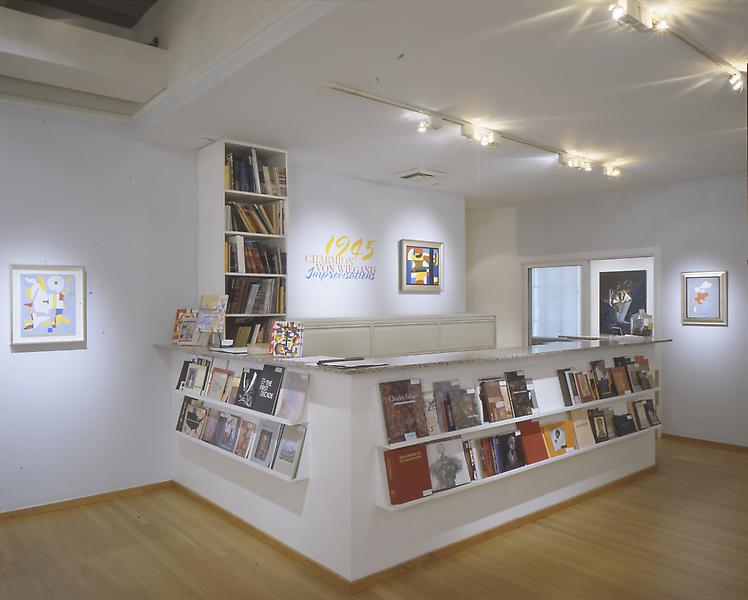

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is pleased to present its third solo exhibition featuring the work of Charmion von Wiegand (American, 1898-1983). Improvisations - 1945 features a selection of thirty works on paper and paintings, all dating from 1945. A student of Neo-Plasticism, von Wiegand's work from this period demonstrates her experimentation with the technique of automatism as well as her awareness of and respect for the avant-garde abstractions of European modernists including Jean Arp, Wassily Kandinsky, Joan Miró, and Piet Mondrian.

In the catalogue essay that accompanies this exhibition, William C. Agee states:

She [von Wiegand] understood that it was possible and even necessary to build on Mondrian, to absorb and adopt his principles but not to replicate the exact look of his paintings…Mondrian taught her to stay open, to be liberated and flexible, so that she did not feel compelled to stay within one abstract vocabulary….

If her fusion of the organic with the geometric strikes us as a willful and odd departure from Mondrian, von Wiegand considered it no such thing. For her it was a natural outgrowth of her study of Mondrian….. If joining the biomorphic and the geometric seemed a contradiction, she believed the resolution of conflict was the essence of great painting….

Charmion von Wiegand was born in Chicago in 1898. The daughter of a Senior Correspondent for the Hearst Newspapers, von Wiegand’s family moved frequently throughout her youth, living in Florida, Arizona, and California; she even attended secondary school in Berlin, Germany. As a result, von Wiegand was an extremely well traveled and well educated young woman by the time she enrolled in classes at Columbia University’s School of Journalism. While at Columbia, she nurtured her abilities as a writer as well as a growing interest in art and art history.

In 1926, while undergoing intense psychoanalysis, von Wiegand professed a desire to become a professional painter. At this time she began teaching herself to paint in earnest, but her primary profession (for the time being) remained journalism. An early champion of American abstraction, von Wiegand was an established art journalist during the 1930s and 1940s, and she wrote for several art world publications including ARTnews, The Journal of Aesthetics, Arts Magazine and The New Masses. In 1941 she formed a close friendship with the great Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian. Mondrian had such an effect on her that she devoted the next year and a half to the study of Neo-Plasticism, and after his death in 1944, she dedicated herself to painting full-time. Although many of her abstract compositions incorporate the Neo-Plastic grid, von Wiegand was never limited by the formal constraints of pure Neo-Plasticism.

This exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated color catalogue with an essay by William C. Agee, Professor of Art History at Hunter College, NY. Visuals are available upon request. For additional information, please contact halley k harrisburg, Director, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is the exclusive representative of the Estate of Charmion von Wiegand.

The 1940s in Context: Charmion von Wiegand and the Language(s) of Abstract Art

William C. Agee

Charmion von Wiegand was neither the first nor the last American artist whose life and work were profoundly changed by an encounter with Piet Mondrian and his art. Indeed, the full story of Mondrian and his impact on American art is a complex one within the larger history of art that has yet to be fully told. In that history, Charmion von Wiegand holds a place of special interest and importance. If her encounter was not the first, its effect on her was surely as swift and dramatic as it was on any American artist.

Von Wiegand had met Mondrian on April 12, 1941, some six months after his arrival in New York. She had gone to interview him for an article – she was then as much a writer as a painter, a very good writer as it turns out, for her essays are intelligent and articulate expositions of the early drive to abstraction in American and European art. She had seen some of Mondrian’s work in the Gallatin Collection at The Gallery of Living Art (housed at New York University), but she had considered it as design rather than painting. However, her experience of encountering Mondrian firsthand immediately changed all that, transforming her view of the world and her understanding of what art could be. She later recalled that when she left Mondrian’s studio at 56th Street and 1st Avenue, she instantly saw the city anew, interpreting its abstract patterns and energies as if through Mondrian’s eyes and art. That moment marked her commitment to the pure language of abstraction, although she did not declare painting as her profession until after Mondrian’s death in 1944. Her art underwent significant changes over the next thirty years, and although she never claimed to be a strict Neo-Plasticist, Mondrian was always her guide and generating spirit. To the end, she was firm in her belief that she had remained true to Mondrian and the principles of Neo-Plasticism.1

Given von Wiegand’s devotion to Mondrian, how do we account for the thirty-one untitled abstractions dating from 1945 (which in this essay will be referred to as the Improvisations)?2 After all, their fluent and flowing shapes recall the language of biomorphism often associated with Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, and on the surface, this language seems to be the very antithesis of the strict geometry central to Mondrian and Neo-Plasticism. The key to reconciling the Improvisations with Mondrian’s influence lies not in a rigid comparison of the two artists’ visual styles, but in examining what von Wiegand understood to be the generating principles and continuing lessons of Mondrian’s art. Seen in this light, the Improvisations - and even von Wiegand’s later work - can be grasped within the context of a fascinating and diverse history of the multiple ways in which American artists responded to Mondrian. Charting such a variegated history makes room for von Wiegand’s version of abstraction in 1945 and 1946, which bears directly on the art of the 1940s and 1950s and extends into the 1960s as an alternative art to the more famous Abstract Expressionism.

Responses to Mondrian were as varied and distinct as his own work, and when referring to “Mondrian,” it is important to specify which Mondrian we mean, since his work can be divided into several particular phases and styles. Artists such as Harry Holtzman, Mondrian’s closest American friend, and Burgoyne Diller began in a strict Neo-Plastic style but later transformed these principles into a distinct and personal geometric art. Other artists, all of diverse outlook and approach, avoided the strict geometry of Mondrian, but looked closely to him in order to draw lessons about clarity and structure for their own art. This process, almost a rite of passage for certain artists, had begun as early as the 1920s, when Stuart Davis first began to engage with Mondrian’s art. In 1930, searching for direction, Alexander Calder visited Mondrian’s studio in Paris. The clarity and purity of Mondrian’s art motivated him to discover his own brand of abstraction. In a process that parallels von Wiegand’s own experience, Calder drew inspiration from Mondrian’s ideas even though the shapes of his mobiles and stabiles were more immediately derived from the biomorphism of Joan Miró. In the early 1940s, Robert Motherwell interpreted Mondrian’s verticals in the crooked bars of his witty painting, Little Spanish Prison (Museum of Modern Art, New York).

After Mondrian’s death on February 1, 1944, one artist after another paid homage to him, and these artists took what they could for their own art. In two 1944 paintings, For Internal Use Only (Reynolda House, Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina) and G&W (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC), Stuart Davis paid tribute to and gently satirized Mondrian’s strict geometry by skewing his famous grid and then inserting within it abstract shapes culled from a Popeye cartoon. Like many artists, Davis later minimized the importance of Mondrian, perhaps as a diversionary tactic, but it is clear that his late work of the 1960s is based on a strong continuing dialogue with Mondrian’s structures and color scheme. The 1944 paintings of both older and younger artists – for example John Marin, Arthur Dove, and even Jackson Pollock – clearly deploy variations of Mondrian’s grid and structural underpinning. The dominating verticals of Dove’s iconic That Red One (Lane Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) are testament to the “new directions,” clearly inspired by Mondrian, that his art took. Mondrian’s 1945 memorial retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art came as a revelation to American artists, a deep source of ideas for further exploration. For example, Pollock was particularly interested in the allover curvilinear patterning of Mondrian’s 1912 tree series, reminding us that Mondrian’s works, which he considered as parts of a whole, were not always strictly geometric. For these artists, including von Wiegand, Mondrian’s work was not a closed and limited system as so many still see it. Rather, it was rich and diverse, filled with infinite possibilities for an artist to expand and develop. While many have seen Mondrian as cold and mechanical, von Wiegand saw his art as sensuous, alive, fertile and open to the limits of the imagination.

Von Wiegand came to understand, indelibly, the open-ended nature of Mondrian’s work through one of the most memorable and telling exchanges in the history of modern American art. After their initial meeting in 1941, she had come to know his work and ideas extremely well, visiting him frequently and reading all she could find on Neo-Plasticism; she even helped him to translate his writings from Dutch into English. We can imagine her complete surprise - even shock - when she walked into the studio in 1942 and saw for the first time Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43) (Museum of Modern Art, New York). Its composition of multiple small and vibrantly colored squares was a radical departure from his earlier grids. Her immediate reaction was to see it as a negation of all that Mondrian had stood for, and in her initial astonishment, she objected: “But Mondrian, it’s against the theory!” To which Mondrian, calm as always, replied: “But it works. You must remember, Charmion, that the paintings come first and the theory comes from the paintings.”

Mondrian moved even further away from classical balance in his last painting, Victory Boogie Woogie (1943-1944) (Gemeentemuseum, The Hague), which was left on his easel at his death, unfinished (but finished enough). The painting announced a new direction for his art, even a new conception of what art itself could be. It was a revolutionary fusion of the linear and geometric with the painterly and expressionistic, of what we take to be polar opposites in painting. The underlying grid structure was there, but it was united now with a tactile, almost relief-like surface of irregular shapes of built-up paint and collage. It seems to have been Mondrian’s acknowledgement and incorporation of the possibilities of a new painterly abstraction, especially as practiced by Pollock, that he had seen and admired in New York. It was a special moment in American art history, a meeting and joining of an older European sensibility with the new directions of a younger generation of American artists. It pointed to a vast range of untapped pictorial options, a huge leap in the language of abstraction, an unlimited future that American art would soon carry forward. Von Wiegand was fully aware of this advance, and she saw Mondrian’s last works as a drive to a new freedom filled with movement and exploration of the unknown, a freedom that went beyond his older closed forms and became nothing less than a “new conceptual structure which would be liberated, flexible, and equilibrated” that would inspire future generations.

The paintings certainly inspired von Wiegand. She understood that it was possible and even necessary to build on Mondrian, to absorb and adopt his principles but not to replicate the exact look of his paintings. By her own account, she was never a strict Neo-Plasticist; Mondrian taught her to stay open, to be liberated and flexible, so that she did not feel compelled to stay within one abstract vocabulary. In her geometric works such as the 1947 City Lights (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), she never hesitated to add half circles and other irregular shapes within an irregular grid, all defined by a gamut of grays, blacks, and yellows, a color palette seemingly as decidedly non-Mondrian as the work’s other elements. In fact, the painting can be seen as a special homage to Mondrian and Broadway Boogie Woogie which enabled her to declare her own freedom, to go her own way in her interpretation of the city in an original and compelling manner.

In other geometric works such as Ka Door (1950), she introduced an expanded range of high keyed and vibrant hues deployed in original configurations. She would have drawn these color lessons from Mondrian’s late art (no wonder she could call Mondrian a “luminous” painter), but the intensity of her hues calls to mind the color of Stuart Davis. She saw the “struggle” within Victory Boogie Woogie: that there were six or seven other paintings buried within it, that it bespoke multiple possibilities not only within the painting, but across several media. The collage elements in Victory Boogie Woogie inspired her to investigate this medium, particularly as developed by Kurt Schwitters, another artist she admired. In St. John The Baptist (1947), she incorporated an array of collaged biblical scenes set in an idiosyncratic variation of an underlying Neo-Plastic grid. Once upon a time, this kind of free-wheeling pictorial exploration was mistaken to be a misinterpretation, a superficial derivation from Mondrian. But we can now understand it as a perceptive and rewarding advance, a move to a highly personal art of the type that Mondrian himself encouraged. It is also an intrinsic part of a uniquely American trait that came to fruition in the 1940s: the ability to learn from the masters of modern art, to take what was useful from a variety of sources and turn it into a personal and convincing art through a process of trial and error, empiricism raised to the level of a full working method. This trait became part of American art history, appearing again in the 1960s, in the idiosyncratic abstraction of artists such as Eva Hesse and Richard Serra, who started with but veered away from the early lexicon of strict Minimalism originated by artists like Donald Judd.

Von Wiegand’s interest in Schwitters signifies that her exploration of abstract art was certainly not limited to Mondrian. The fluid shapes of the Improvisations indicate her awareness of and respect for the work of Jean Arp, Joan Miró and Wassily Kandinsky. In fact, the starting point of this series was the Surrealist technique of automatism - the quick, uncensored response to psychic impulses practiced by artists such as Max Ernst and Hans Richter. It is little wonder that she was attracted to the practice, since she had resolved to become an artist as a result of intensive psychoanalysis in the 1920s and had been familiar with Surrealism since the 1936 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. Richter had encouraged her to explore