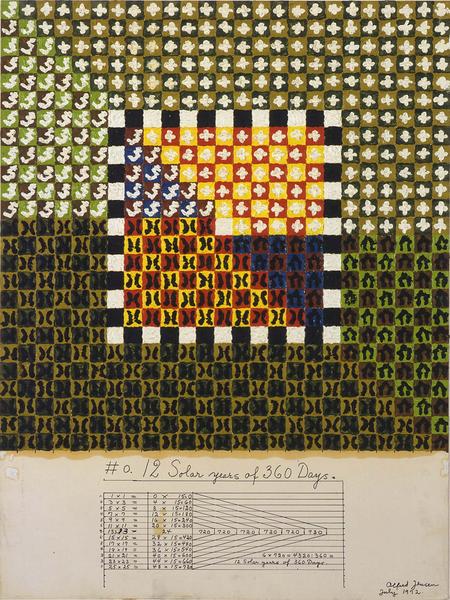

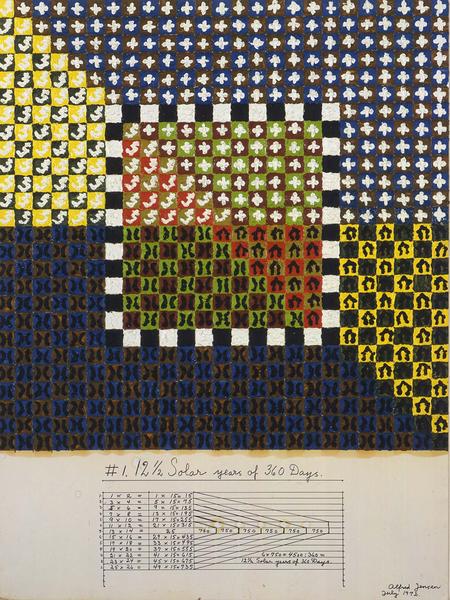

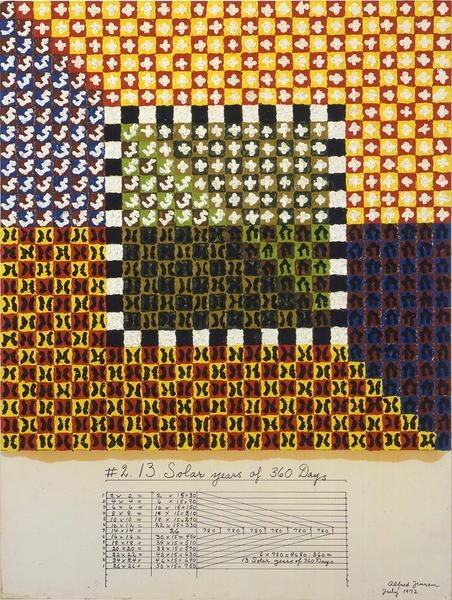

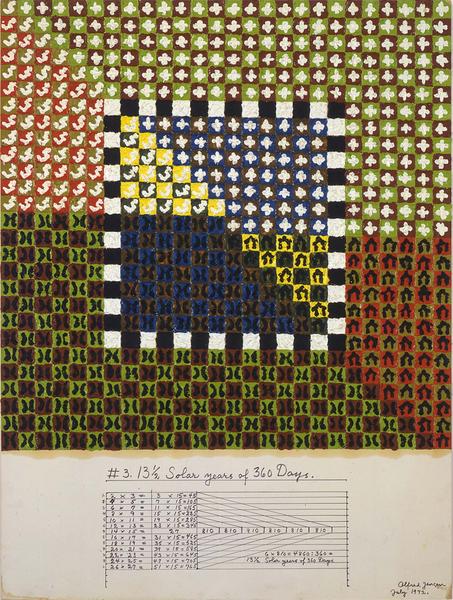

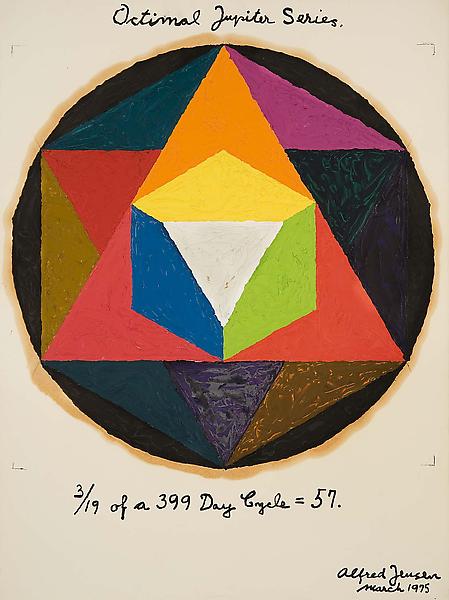

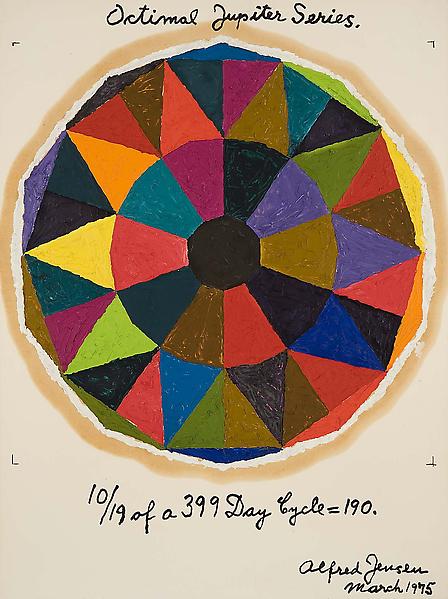

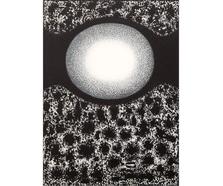

“The dark of the universe and the light of the sun are both sources of energy. In exploring the prism a similar phenomenon takes place. A total prism is a circular unit of 360°. This unit is split in two half circles, each 180°. One part is the black prism, the other part is the white prism.” [1]

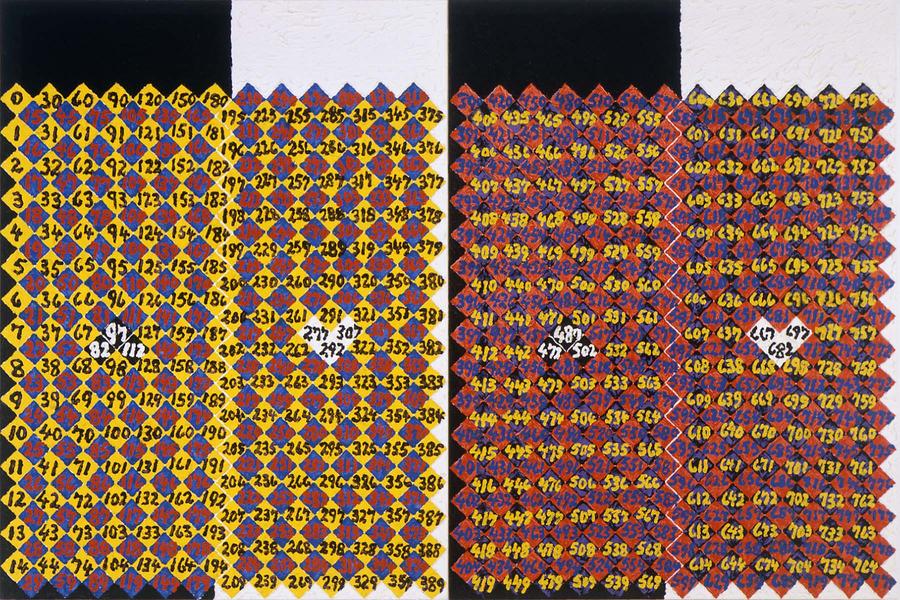

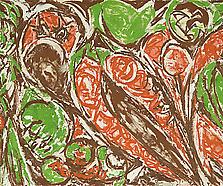

For a viewer encountering Jensen’s artwork for the first time, his compositions can be as intimidating as they are alluring. Distinguished by colorful, grid-like paintings executed in alluring oil impasto, Jensen’s art taunts its viewer with patterns of colors and numbers. Like a torn photograph, his paintings entice us with a mystery we may never solve. Fortunately, however, the answer to the mystery is not nearly as important as the process of exploration.

A master of composition, Alfred Julio Jensen was born in Guatemala City, Guatemala in 1903. Following the death of his mother in 1910, Jensen was sent to his father’s native Denmark, where his uncle raised him. In 1917, he left school and found jobs on various ships, which enabled him to travel extensively. After the death of his father in 1922, Jensen settled in California, where he worked during the day and attended high school at night. In 1925, a scholarship enabled him to enroll in classes at the San Diego Fine Arts School, but in 1926, Jensen left San Diego and sailed for Germany, in order to study at Hans Hofmann’s celebrated Schule für Bildes Kunst. Having forgotten all but the first initial of Hofmann’s name, Jensen originally enrolled in classes with at Moritz Heymann’s art school. Fortunately, renovations in Heymann’s classrooms forced his students into Hofmann’s school. In Munich, Jensen met Carl Holty and Vaclav Vytlacil, as well as Saidie Adler May, a wealthy American art collector who eventually became Jensen’s patron. Feeling stifled by Hofmann’s approach to art, Jensen left school again and with May’s help enrolled in the Académie Scandinave in Paris, where he found a close friend and mentor in artist Charles Dufresne.

Jensen spent much of the 1930s and 1940s traveling in Europe and the United States with May and advising her on her art collection. While reading Goethe’s Theory of Colors (Zür Farbenlehre), he began to construct color diagrams based on his studies. He also researched the ancient Mayan calendar, Babylonian astronomy, and M. E. Chevreul’s law of simultaneous contrast—which stated that "In the case where the eye sees at the same time two contiguous colors, they will appear as dissimilar as possible, both in their optical composition and in the height of their tone."[2]

In 1951, Saidie May died, and Jensen settled in New York City, where the following year, the John Heller Gallery mounted the first exhibition of his work—a collection of twelve paintings based on Goethe’s theories and executed in prismatic colors. In New York, Jensen befriended numerous abstract expressionist painters and was especially close with Mark Rothko. In later decades, his artist friends included representatives of pop, minimalist, and conceptual art as well. But despite his many friendships in the heart of the New York art world, Jensen remained firmly separated from any contemporary art movement. Instead, he continued to work on paintings and drawings that synthesized the many knowledge systems—ancient and modern, scientific and spiritual—that captivated his imagination.

A voracious scholar, Jensen pursued interests in a variety of areas including electromagneticism and physical chemistry. During a 1964 trip to Greece, he embarked on a detailed study of “ancient Greek architectural and numerical ratios,”[3] and after his return, he began his Acroatic Rectangles series, based on these studies. The many systems, patterns, and esoteric theories Jensen pursued and drew inspiration from throughout his life were a central part of how he made art, but they may not be essential to understanding Jensen’s work. As Merlin James argues, “Jensen’s ‘theory’—as explored in notebooks, in annotated texts . . . in drawings and diagrams . . . —is . . . a kind of fantastical creation myth that permitted him to generate his art.”[4]

Jensen exhibited regularly throughout his career, in group and solo shows. In 1961, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York gave him a one-man exhibition; in 1964, his work appeared in the Venice Biennale; he participated in Dokumenta IV (1968) and V (1972); he had two traveling retrospective exhibitions during his lifetime; and in 1985—four years after his death— the Guggenheim also organized a major retrospective. His work can be found in numerous national and international collections, including the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Dallas Museum of Art, Texas; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California; Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Kunsthalle, Basel, Switzerland; and Seibu Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan.

[1] Alfred Jensen, “Artist’s Statement, 1977,” Peter Jensen, Regina Bogat Jensen, and Anna Jensen, Alfred Jensen website. http://www.alfredjensen.com/writings/statement1977.html. Accessed September 2010.

[2] M.E. Chevreul, “Law of Simultaneous Contrast,” quoted by William Warren, “Divisionist Color Theory and

Painting Techniques,” http://www.brown.edu/Courses/CG11/2005/Group161/index.htm. Accessed September 2010.

[3] Stephanie Skestos, “The Acroatic Rectangle, Per XIII, 1967 by Alfred Jensen,” The Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 25, No. 1 (1999), 32.

[4] Merlin James, “Alfred Jensen,” The Burlington Magazine, v.144, n.1187 (February, 2002), 130. See also Peter Schjeldahl, “Jensen's Difficulty,” Alfred Jensen: Paintings and Works on Paper exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1985), which James credits with providing a foundation for his own observations.