"I have felt that people's images reflect the era in a way that nothing else could." [1]

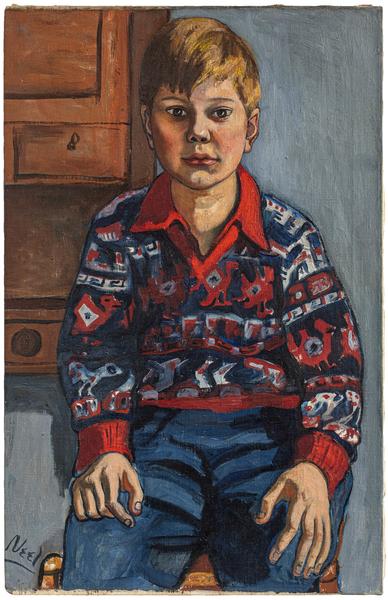

A self-described “collector of souls,” Alice Neel is celebrated for almost single-handedly reviving the art of portraiture in the twentieth century, although she preferred the term “paintings of people” to that of “portrait.”[2] Neel was born in 1900 in Merion Square, Pennsylvania. Her mother, Alice Concross Hartley, was a descendant of one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence, and her father, George Washington Neel, worked as an accountant for the Pennsylvania Railroad. From an early age, Neel demonstrated an independence and determination generally discouraged in young women at the time. Upon finishing high school in 1918, she took the civil service exam and got a job as a secretary for Army Air Corps Lieutenant Theodore Sizer (who later became an art history professor at Yale). In the evenings, she took classes at the Philadelphia Museum’s School of Industrial Art. In 1921, she enrolled in the Philadelphia School of Design for Young Women (now the Moore College of Art and Design) and completed her degree, aided by a state scholarship. She was put off by the dominant style espoused by the school at the time, impressionism, and found herself drawn instead to the realism of the Ashcan school, whose focus on the popular and the urban had a profound impact on her work. As she once explained, “I like to paint people, you know, who are in the rat race, suffering all the tension and damage that’s involved in that. Under pressure, really, of city life, and of the awful struggle that goes on in the city.”[3] Neel also excelled at portraiture, winning honorable mention in a school competition two years in a row.

The late 1920s and 1930s were tumultuous years for Neel. After she graduated from the School of Design in 1925, Neel married fellow artist Carlos Enríquez, the son of a wealthy Cuban family. In 1926, the couple moved to Havana, and Neel gave birth to her daughter, Santillana. Struck by the immense wealth gap in Havana, she painted the impoverished individuals she encountered. In 1927, a review of the XII Salón de Bellas Artes placed her work among the exhibition’s highlights. That same year, Neel returned to New York, and she and Enríquez settled in the Bronx, where their baby daughter soon died of diphtheria. The couple had a second child, Isabetta, the following year, and in 1930, Enríquez brought Isabetta to Havana while he left for Paris and Neel remained in the US. Although Neel was initially glad for the time alone to paint, she soon suffered a nervous breakdown and after two suicide attempts in January of 1931, spent the better part of the year recovering in a hospital and sanitarium. In 1932, she moved into an apartment in Greenwich Village and participated in the first Washington Square Outdoor Art Exhibit. Living in the Village brought Neel into the heart of the Depression-Era New York art world, and in 1933, she joined the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). Her daughter came to New York for a visit the following year, and Neel painted a portrait of her, which also recorded the last time Neel would ever see her child. Isabetta was raised in Havana by Enríquez’s parents, and Neel effectively lost her second daughter. Soon after, her lover at the time destroyed over three hundred drawings and more than fifty paintings—including the portrait of Isabetta—in a jealous rage. Neel left him and moved into an apartment on West 17th Street, where she reconstructed the portrait of her child. Cut from the PWAP’s payroll in 1935, Neel became an easel painter for the Works Progress Administration in 1936. That same year, her painting Nazis Murder Jews received honorable mention at the American Artists’ Congress exhibition held at ACA Gallery. In 1938, Contemporary Arts Gallery mounted Neel’s first solo exhibition, for which she received very favorable reviews.

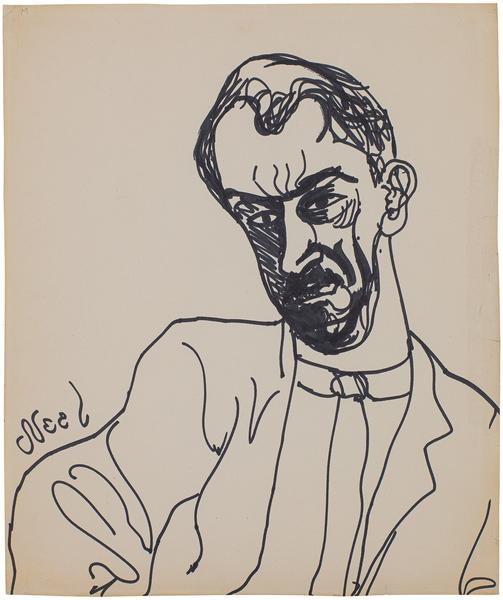

By 1941, Neel had given birth to two more children and was now a single mother struggling to support her sons as an artist. She moved to East Harlem and through the WPA began teaching at a day school; when the WPA was dissolved in 1943, she survived on welfare for roughly a decade. Despite personal and financial hardships, Neel continued to believe in her talent and pursue her avid passion for art. She painted portraits of her East Harlem neighbors, finding a vitality in the neighborhood that suited her deep commitment to capturing the beauty and anguish of ordinary city life. Although she lived roughly one hundred blocks away from the heart of New York’s art scene, Neel attended discussions and debates at The Club, the apartment at 39 East 8th Street where artists of the New York School held meetings about the future of painting. In 1948, she began to draw for the communist journal Masses and Mainstream (whose contributors and editors included Paul Robeson, Lloyd Lewis Brown, and W.E.B. Du Bois), illustrating two short stories by friend and author Philip Bonosky—The Wishing Well (1949) and I Live on the Bowery (1950). Neel’s communist sympathies and association with leftists brought her under suspicion in the charged atmosphere of the Cold War, and in 1955, she was interviewed by the FBI. “According to her sons, Neel asked the agents to sit for portraits. They declined.”[4]

Neel had been steadily painting for roughly forty years before she began to receive wide-scale recognition in the 1960s. Marginalization within a male-dominated art world was a shared experience among women artists, but Neel’s dedication to figural representation in the era of abstraction compounded her invisibility. Like that of many mid-century figural painters, Neel’s work was dwarfed by the monumental presence of abstract expressionism and a version of modern art that looked increasingly inward. But even her relationship to figural representation was complicated, which only further confounded attempts to pigeonhole her into a marketable or exhibit-able slot. As Jeremy Lewison writes, “Neel fell outside the expected norms of leftist painters for whom works amounted to rather obvious allegories of the social situation . . . she rejected the post-cubist approach to the figure that Picasso and his followers adopted; and she avoided abstraction as a mode of painting because of its narrative limitations.”[5] By the 1960s, Neel had reached her mature style, blending elements of realist representation with expressionistic aspects such as her frequent use of green as a base for skin tones, a choice that infuses her paintings with an unsettling quality.[6] Fascinated with psychology, Neel captured the inner life of her sitters by posing them, engaging them in conversation, and pushing them towards the limits of their own psychological comfort. Thus, her portraits have often been described as documenting an encounter between sitter and painter rather than merely creating a likeness in paint of a particular person. At the age of sixty-three, Neel finally obtained regular gallery representation when she joined the stable of artists at the Graham Gallery, and in 1964, Muriel Gardiner, a psychiatrist, became a benefactor for Neel, providing her with an annual stipend for the rest of her life. Despite these modest successes, Neel remained dedicated to questions of equality, including those within the art world. In 1968, she protested the absence of women and men of color in a Whitney Museum exhibition on 1930s American art, and in 1969, she joined the protests against the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Harlem on My Mind show. Among the organizers of the protests was Neel’s close friend and member of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) Benny Andrews; Neel attended several BECC protests. Neel and Andrews had met and become close friends in 1966, when the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library mounted a two-person show dedicated to their work. In 1972, Neel completed a portrait, Benny and Mary Ellen Andrews (now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art), and Andrews painted his Portrait of Alice Neel in 1987.

It was not until the 1970s that Neel’s career began to soar, aided in part by the women’s movement, which, as art historian Mary Garrard (who also sat for Neel) explains, “gave her a context in which to be understood. She had labored forty years without recognition, first because she was a figurative painter in an era when abstraction was dominant, and second, because she was a woman. The feminist movement validated her in both respects. Obviously, it supported her as a woman, but it also validated her commitment to the specific and individual, as opposed to the mythic universals of abstract modernism.”[7] In 1970, Neel began painting portraits for Time magazine. Her subjects included Senator Edward Kennedy, President Franklin Roosevelt, and feminist activist/intellectual Kate Millett. In 1974, the Whitney Museum organized her first retrospective exhibition, and Neel received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. The following year, the Georgia Museum of Art mounted Alice Neel: The Woman and Her Work, and in 1976—the same year as the major traveling exhibition Women Artists 1550-1950, which included a work by Neel—she was granted membership to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1979, Neel received the Outstanding Achievement in the Visual Arts Award from the National Women’s Caucus for Art, and in 1982, New York mayor Edward Koch—who had recently commissioned a portrait from Neel—held a dinner in her honor. By 1984, the woman who spent the first half of her career in poverty and obscurity was enough of a cultural icon to appear on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, not once, but twice.

Alice Neel died of cancer in 1984, leaving a painted history of the decades she witnessed, a legacy that illustrates her fundamental belief in the value of portraiture. Shortly before she died, Neel collaborated with Patricia Hills on her own biography, published in 1983. In almost every year since her death there has been a solo exhibition of her work at a museum or gallery in the United States or Europe. Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has included her work regularly since 2005, most recently in the exhibition The Time is N♀w. In 2007, Neel’s grandson Andrew made a documentary film about the artist, which investigated her work, her life as a woman, and the years of domestic violence she and her sons suffered. Neel remains a recurring figure of intrigue for feminist art historians because of the contradictions and complexities she had to navigate as a gifted but flawed person whose talent and domestic responsibilities coincided with the first wave of the feminist struggle for women’s equality. Her paintings of people, a record of celebrities as well as ordinary New Yorkers, continue to provoke and inspire.

Neel’s work is represented in numerous museum collections worldwide including the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL); Blanton Museum of Art (Austin, TX); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC); The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY); Moderna Museet (Stockholm, Sweden); Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, CA); Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, MA); Museum of Fine Arts (Houston, TX); Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY); National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC); National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC); Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia, PA); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, CA); Tate Modern (London, England); Wadsworth Atheneum (Hartford, CT); Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY); and Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven, CT).

[1] Alice Neel quoted in Henry Hope, “Alice Neel: Portraits of an Era,” Art Journal vol. 38, no. 4, Summer, 1979, 281

[2] Robert Silberman, “Alice Neel, Minneapolis Review” Burlington Magazine vol. 143, no. 1181, August, 2001), 518

[3] Alice Neel quoted in footage from Michel Auder’s Portrait of Alice Neel (1976-1982) included in the documentary Alice Neel (Andrew Neel, 2007)

[4] “Alice Neel Biography: 1950s,” http://www.aliceneel.com/biography/1950.shtml

[5] Jeremy Lewison, “Beyond the Pale: Alice Neel and Her Legacy,” Art & Australia vol. 48, no. 3, 2011, 503

[7] Mary Garrard, “Alice Neel and Me,” Woman’s Art Journal vol. 27, no. 2, Fall - Winter, 2006, 5