“The important mission of the artist is to portray scenes which the layman neglects to see in nature; to show beauties which the public never think of beholding; and to imbue his paintings with a thought that is not commonplace. In short, he must uplift the spectator’s mind to higher planes.”[1]

An idiosyncratic, eccentric and extremely prolific outsider artist, Louis M. Eilshemius was born in 1864 on his family’s estate, Laurel Hill Manor, in Arlington, New Jersey, to Henry G. and Cécilie Elise Eilshemius, the sixth of eight children. From a young age, Eilshemius was educated in Europe, attending school in Geneva, Switzerland and Dresden, Germany, where he received his first lessons in art. By 1881, Eilshemius had returned to New York, where his father had made his fortune in imports, and was working as a bookkeeper; requests to study art were denied by his father. In 1882, he enrolled at Cornell University to study agriculture, continuing to write, draw and paint on his own. Having at last obtained his father’s permission to pursue art, Eilshemius enrolled at the Art Students League from 1884 to 1886, studying privately with landscape painter Robert C. Minor, and departed later that year for Paris to attend the Académie Julian. Following his return to New York in 1888, paintings of his were selected for exhibition at the National Academy of Design and at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Having also studied with the landscape painter Joseph Van Luppen in Antwerp the summer before his return, Eilshemius’ early works were predominantly landscapes, demonstrating the influence of the French Barbizon and American Hudson River Schools as well as the painters Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, George Inness and Albert Pinkham Ryder, whose New York studio he later visited in 1908.

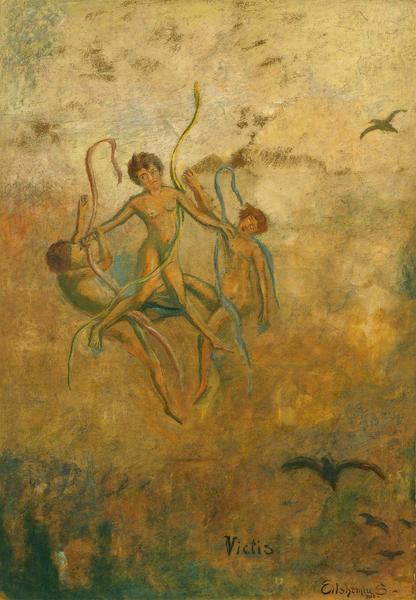

Around this time, as a marker of his own unconventional take on his artistic persona and ongoing sense of personal reinvention, he was known to sign his paintings “Elshemus,” from 1890 until 1913, when he returned to the proper spelling. In 1892, his father died, leaving a substantial estate which provided him with the means to travel. Indeed, that same year, Eilshemius traveled to Europe and North Africa, providing subjects that would inspire and inform subsequent work. The artist briefly established a studio in Los Angeles but, overcome by solitude, he quickly returned to New York. Upon his return, in 1895, Eilshemius began regularly publishing his writing, including two volumes of verse, Moods of Soul and Songs of Spring and Blossoms of Unrequited Love (1895), his only novel Sweetbrier (1901) and Songs of Southern Scenes (1904). In 1897, his first one-man exhibition took place in the back room of Philip Suval’s frame shop; the show went unnoticed. Further travels included a trip to Hawaii, Samoa and other islands of the South Pacific, and New Zealand in 1901 and, back in the United States, to Memphis, New Orleans and Florida in 1902. The following year, he traveled again to Europe, working in Rome but returning to New York shortly thereafter in 1904. Unable to make meaningful social and professional contacts, he terminated his membership with the Salmagundi Club, which he had joined in 1898. Subsequent years were productive, painting a large series of Samoan subjects based on his earlier travels. In 1907, he once again visited Europe and published six books; throughout his career he self-printed at least thirty. Literary work also included his roles as editor of The Art Reformer (in 1909, 1911-12) and Three Arts’ Friend (1925-1926). In 1909, an exhibition, Paintings in Three Colors, held at his studio on 23rd Street in Manhattan proved unsuccessful and dejection began to figure in his work; he also began printing self-aggrandizing proclamations for publicity as a way of coping. In 1911, his mother died and he continued to live with his older brother Henry, on whom he became financially dependent, in the family’s Manhattan brownstone. In 1913, several paintings were rejected by the Armory Show exhibition committee and the years between 1914 and 1918 saw a series of unsuccessful studio exhibitions. The paintings of this time became increasingly less conventional and punctuated by an element of fantasy, depicting voluptuous nudes and moonlit landscapes. With whimsical flourish, Eilshemius also painted sinuous frames onto these pictures, thereby adding both dimensionality and flatness to his lyrical and romantic scenes. He also experimented with different supports, switching from canvas to cardboard and even cigar box lids.

Eilshemius’ turn towards success came in 1917 when two paintings, Supplication (Rose Marie Calling) and The Gossips, were exhibited at the Society of Independent Artists at the Grand Central Palace where they were noticed by Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp’s discovery and praise of Eilshemius’ work drew the attention of the international art world. Two solo exhibitions were held by the Société Anonyme, sponsored by Duchamp and patron Katherine S. Dreier, in 1920 and 1924. The first exhibition failed to draw positive criticism, driving the artist to give up painting in 1921, but the second exhibition received strong support from critics, including Henry McBride of The New York Sun, who, admitting his own delay in recognizing Eilshemius’ talent, wrote “Suddenly, like another St. Paul, I see a great light and the scales drop from my eyes. The pictures in the Anonyme gallery are completely lovely.”[2] Continued success also included a solo exhibition at Valentine Gallery, although negative criticism deterred dealer Valentine Dudensing from holding another exhibition of the artist’s work for six years. Exhibitions at the gallery resumed in 1932 with Romantic Drama and Lyrical Poetry, which covered the full range of Eilshemius’ oeuvre and established the foundation for his public reputation; both exhibitions received favorable reviews. That year, a painting was acquired by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and an exhibition held at Durand-Ruel Galleries in Paris received critical acclaim. Between 1932 and 1941, Eilshemius saw a steady rise to fame, with over twenty-five solo exhibitions in New York alone and numerous mentions in the press. At this time, his success both confounded and fueled his perceived peculiarities and erratic behavior and, injured in an automobile accident in 1932, Eilshemius became increasingly reclusive. In 1939, the artist’s biography, And He Sat Among the Ashes, written by William Schack, was published by the American Artists Group. Schack and members of the group would go on to raise money in order to assist an ailing Eilshemius, whose brother Henry had died in 1940, thus leaving him alone and impoverished. In December 1941, Eilshemius died of pneumonia.