“So if you consider art as a privilege, then, by definition, you feel that you do not deserve it. You are continually denying yourself something – denying your sex, denying yourself the tools that an artist needs – because to be a sculptor costs you money. If you consider art a privilege instead of something that society will use, you have to save and suffer for your art, for what you love; you have to deny yourself in the cause of the art. I felt I had to save my husband’s money rather than do sculpture that costs money. So the materials I used in the beginning were discarded objects.” *

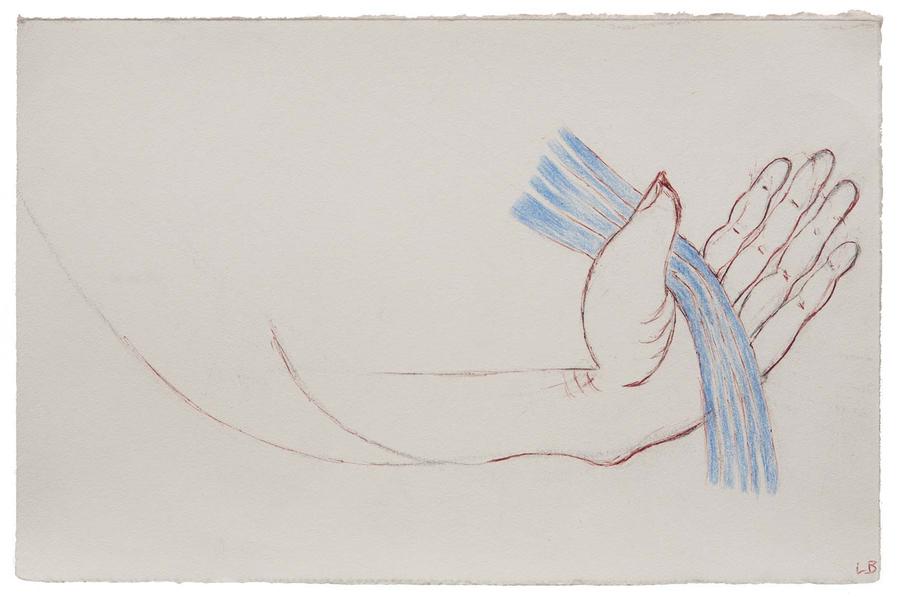

Acknowledged today as a preeminent sculptor of the past half-century, Louise Bourgeois was largely ignored before the 1970s when the feminist movement in art brought her sexually charged abstract sculptures in marble, latex, bronze, and wood to wide-scale public attention. Born in 1911 in Paris to tapestry restorationists Louis and Josephine Bourgeois, Louise would often help in the tapestry studio when she was a child, by drawing in sections that needed restoration. She soon became an expert at drawing legs and feet (the parts of the tapestry towards the bottom that most often needed work), and these shapes reappear throughout her body of work. Bourgeois’s childhood had a psychological impact on her art as well; her long-suffering mother and charming but chronically unfaithful father produced a household filled with anxiety for the young Bourgeois, which later provided the content for many of her pieces.

In the 1930s Bourgeois attended the Sorbonne, receiving the Baccalauréat in philosophy before studying art history at the Louvre and studio art at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Her interest in sculpture sparked when she attended the atelier of Fernand Léger. There, she met surrealists and cubists such as Max Ernst, André Breton, and Marcel Duchamp, all of whom she would later see in New York during World War II. In 1938, Bourgeois opened an art gallery, specializing in works on paper by nineteenth and twentieth century French masters. At this time, she met US art historian Robert Goldwater, and the couple married that same year. Bourgeois moved to New York with Goldwater, took courses at the Art Students League, and began drawing, painting, and making prints. When Bourgeois was pregnant with her third son, in 1941, the family moved to New York’s oldest building, the now-demolished Stuyvesant’s Folly at 142 East 18th Street. Inspired by the vivid light on the building’s roof as well as its placement in the middle of the city but above the chaos of the street, she began using the roof as an open-air studio, creating her Personages sculpture series. Tall, lean, rectangular wood sculptures with rounded elements, the works “reflect[ed] not only the forms of the surrounding skyscrapers and therefore the vocabulary of modernism,”† but as Bourgeois herself explained, they also “were conceived of and functioned as figures, each given a personality by its shape and articulation, and responding to one another. They were life-size in a real space, and made to be seen in groups.”‡