ROBERT COLESCOTT (1925–2009)

“If you decide to laugh, don't forget the ‘humor is the bait,’ and once you've bitten, you may have to do some serious chewing. The tears may come later.”[1]

–Robert Colescott

Robert Colescott was born in Oakland, California in 1925. His parents had relocated there from New Orleans in 1919 to escape the violence of the Jim Crow South and provide their future children access to an integrated, rigorous, and affordable education. His father was a violinist who had fought in France with the segregated 92nd Division during the First World War before taking a job as a waiter on the Southern Pacific railway. His mother, a pianist, had been a teacher in New Orleans but was forced to resign when she married because schools would not allow married women to teach. Colescott grew up in a diverse, middle-class neighborhood, and his parents nurtured his intellect as well as his love of music and drawing. The Colescott’s were part of a small but significant black cultural community that included artist Sargent Claude Johnson, a family friend who would support and encourage Colescott’s artistic ambitions as he got older.

When Robert finished high school in 1942, he volunteered for the US Army, serving in Europe and the Pacific. Upon his return, he used funding from the GI Bill to attend San Francisco State University, where he intended to study international relations and economics. Although he had been drawing and painting since childhood, he never saw art as a potential career until a college counselor advised Colescott not to pursue international relations because a career with the State Department was unlikely for African Americans. In 1946, he transferred to the University of California, Berkeley, where the West Coast bastion of the Abstract Expressionist movement was in full swing. When he finished his BFA in 1949, Colescott was working primarily in an abstract style, and traveled to Paris with the intention of studying with Fernand Léger. Though Léger refused to look at Colescott’s portfolio because it consisted only of abstract work, he invited Colescott to join a small group of students working out of his studio. Léger would have a profound influence on Colescott, encouraging him to question the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and inspiring his return to figuration. In 1950, Colescott returned to California to pursue his MFA at Berkeley, where he was one of only a few figural painters among such dedicated abstractionists as Jay DeFeo and Sam Francis.

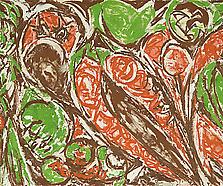

In the early 1950s, Colescott finished his MFA and moved to Seattle, where he taught junior high school during the day and dedicated the rest of his time to painting: “After dinner I’d go down to my basement studio and paint until 2 and 3 in the morning. I accepted the fact that I taught, but I wouldn’t accept the fact of being a teacher… I wanted to solve the problems of paint. I kept trying to learn how to use my brush with some sense of strength and energy and personality, and so I painted all kinds of things: I painted figures, I painted still lifes, I painted flowers, I painted 22 landscapes. I just painted everything.”[2] Colescott began exhibiting in solo and group shows in the early 1950s, to favorable reviews, and in 1957, he moved to Portland, Oregon, joining the faculty at Portland State University. In 1961, he signed on with the Fountain Gallery of Art, and in 1963, the Portland Art Museum mounted a solo exhibition of his work.

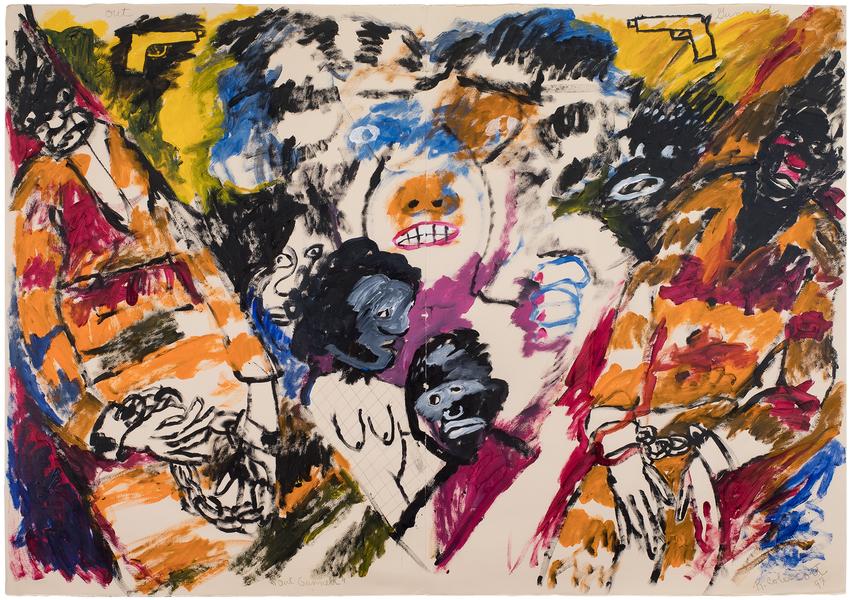

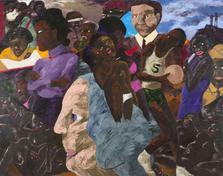

It was in Portland that Colescott began working in a high-contrast, boldly colored figural style that would soon evolve to his mature style, a trajectory that was accelerated by his first trip to Egypt. In 1964, he became an artist-in-residence at the American Research Center in Cairo, Egypt, an experience that had a profound impact on how he understood the history of art and the place of people of color within it. Living in Cairo for three years, Colescott explained he felt a profound influence from the “three thousand years of a ‘non-white’ art tradition and by living in a culture that is strictly ‘non-white,’” he stated. “I think that excited me about...some of the ideas about race and culture in our own country; I wanted to say something about it.”[3] In 1967, he left Cairo for Paris, where he taught for several years before returning to the United States in 1970. His residency in both cities coincided with the dismantling of the French empire as more and more former African colonies attained independence. He also witnessed the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the anti-war movement, and the rise of Black Nationalism from a vantage point beyond the scope of US media. These events propelled critiques of European colonial and racial domination into the mainstream, which found their way into Colescott’s subsequent work.

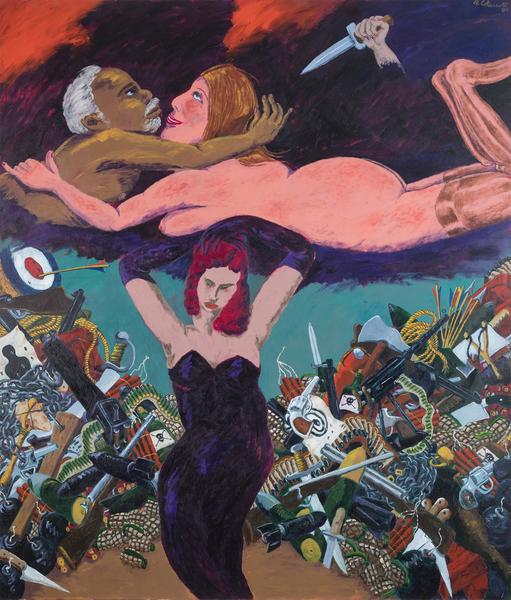

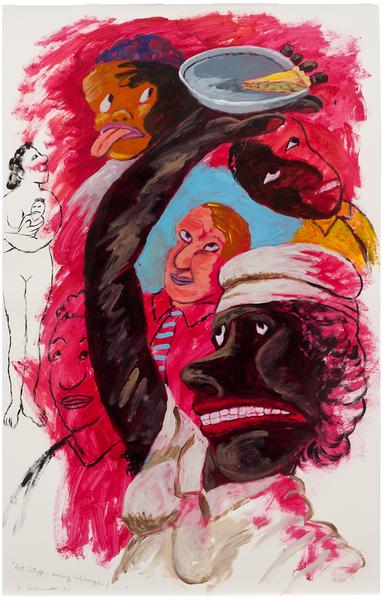

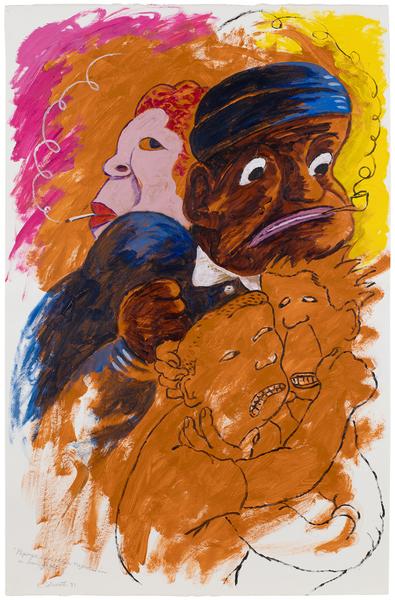

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Colescott set out to challenge the canonical narratives of “Western civilization” through his paintings, arriving in the style for which he is best known. Developing a cartoonish approach to figuration inspired by his childhood love of comic strips, the artist set out to skewer social conventions pertaining to race and gender, and how each are represented in American visual culture. Using bright palettes and sinuously exaggerated figuration, Colescott created compositions centered on the juxtaposition of

[1] Colescott quoted in Huey Copeland, “Truth to Power,” Artforum International vol.48, no. 2, October 2009, 59-60.

[2] Sharon Fitzgerald, “Robert Colescott Rocks the Boat, Painter’s work shown at June 1997 International Festival,” American Visions, June 21, 1991 as quoted in LeFalle-Collins.

[3] Colescott as quoted in Emily Langer, “Robert Colescott Dies at 83: Painter's Take on Classics Tackled Social Ills,” Washington Post, June 12, 2009.