“My aim is to express in a natural way what I feel . . . is in me, both rhythmically and spiritually, all that which in time has been saved up in my family of primitiveness and tradition and which is now concentrated in me.”[1]

Born in Florence, South Carolina in 1901, William Henry Johnson demonstrated an aptitude for art from an early age. Given his parents’ restricted income, Johnson, the oldest of five children, spent much of his childhood working to help the family survive. In 1918, “realizing that his opportunities for professional and artistic development were severely limited in a small, segregated southern town, Johnson boarded a train for New York City,”[2] where he stayed with an uncle in Harlem. There, Johnson worked various jobs until 1921, when he was accepted into the National Academy of Design (NAD). From 1921 to 1925, he studied with Charles Hawthorne at the NAD, and he took private lessons with painter George Luks. Hawthorne, who had founded the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown and taught summer classes there, had a profound impact on Johnson’s development as an artist. From 1924 to 1926, Johnson spent summers in Provincetown, studying with Hawthorne and working at the school to pay for his tuition. Hawthorne encouraged and supported Johnson, and in 1926, when Johnson was denied the NAD’s prestigious Pulitzer Traveling Scholarship, “Hawthorne and others were so incensed by this apparent act of discrimination that they privately raised the funds to support Johnson’s study in France.”[3]

In 1926, Johnson traveled to Paris, making a pilgrimage to the studio of Henry Ossawa Tanner. In 1928, he moved to southern France, where he met and befriended German expressionist Christoph Voll, his wife, and her sister Holcha Krake, a Danish artist working in ceramic and textile. The quartet traveled together extensively, making art and visiting museums in France, Germany, Belgium, and Luxembourg. In 1929, Johnson returned to New York and submitted some of his paintings to the William E. Harmon Foundation’s annual competition. He won a gold medal in the Foundation’s “Distinguished Achievements Among Negroes in the Fine Arts Field” category, and four of his paintings were chosen for inclusion in the Harmon Foundation annual exhibition. After trips to Florence, South Carolina—where his hometown welcomed him with an exhibition of his work—and Washington, DC—where he visited with Alain Locke—Johnson returned to Europe in 1930. He married Krake, and the couple spent eight years living and working in Scandinavia.[4] During this time, Johnson painted a series of landscapes characterized by expressionistic lines and vivid colors.

In November of 1938, Johnson returned to the United States with Krake. They settled in New York, and in 1939 Johnson went to work for the Federal Art Project, teaching at the Harlem Community Art Center, a position he held until 1943. The Art Center had begun as a school established by Augusta Savage but was taken over by the WPA and turned into one of its neighborhood art centers during the Depression. It was a hub of cultural activity, drawing in artists like Norman Lewis, Jacob Lawrence, and Gwendolyn Knight. Johnson completely transformed his approach to art; he abandoned landscape painting and expressionism in favor of narrative images of African Americans executed in a deliberately simplified—or as he put it, “primitive”—style. The idea of the primitive had held an appeal for Johnson throughout his career; for him, the term was synonymous with “folkloric.” Unlike European modernists who understood the “primitive” within a colonial framework that placed Europe at the top of an imagined scale of development, Johnson’s primitivism had more to do with “the community values and folkways of all marginalized peoples. ‘Primitives,’ concluded Johnson, ‘can be found all over the world.’”[5]

Johnson’s success in the 1940s was coupled with tragic personal events. A 1941 solo exhibition at the Alma Reed Galleries was followed by a studio fire in 1942 and the death of Krake less than two years later. Bereft, Johnson decided to move back to Denmark, where the couple’s friends and Krake’s family still lived. In Europe, his behavior became increasingly erratic, and in 1947, diagnosed with a mental illness, he was sent to a hospital in Long Island, where he remained until his death in 1970.

In 1971, the National Museum of American Art (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum) organized William H. Johnson, 1901–1970, a major traveling retrospective exhibition accompanied by a catalogue with an essay by Adelyn D. Breeskin. A second Smithsonian exhibition was organized in 1991 titled Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson, featuring a catalogue with scholarship by Richard J. Powell. The museum presented a third solo exhibition for the artist, William H. Johnson’s World on Paper, curated by Joann Moser in 2006; it then traveled to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX; Philadelphia Museum of Art; and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, AL. With over a thousand paintings in its possession, the Smithsonian American Art Museum represents the largest collection of works by William H. Johnson. In 2015, William H. Johnson: New Beginnings was presented in the artist’s hometown at the Florence County Museum, Florence, SC.

In 1995, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery mounted the first commercial gallery exhibition of Johnson’s work in over fifty years: William H. Johnson: Works from the Collection of Mary Beattie Brady, Director of the Harmon Foundation. The gallery has also included the artist’s work in numerous group exhibitions, including its celebrated series African-American Art: 20th Century Masterworks (1993-2003). In recent years, Johnson’s work has been featured in group exhibitions held at institutions across the country, including America Is Hard to See, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (2015) and The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (2017). In 2018 alone, Johnson’s work was displayed in such exhibitions as Something to Say: The McNay Presents 100 Years of African American Art, McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX; Outliers and American Vanguard Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Lenfest Center for the Arts, Columbia University, New York, NY; and Watercolor: An American Medium, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA.

In 2020, Johnson’s work is on view in Spirit of the Renaissance: The Art of William H. Johnson & Malvin Gray Johnson at the Hampton University Museum in Hampton, VA and Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art at the Belvedere in Vienna, where it traveled from the Barbican Art Gallery in London. Johnson is also featured in the spotlight installation “In and Around Harlem” of the permanent collection exhibition Collection 1940s-1970s at the newly re-opened Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Major institutions with work by William H. Johnson in their permanent collections include the Art Institute of Chicago (IL); The Baltimore Museum of Art (MD); The Cleveland Museum of Art (OH); Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA); Hampton University Museum, Hampton University (VA); The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY); Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MA); The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (TX); The Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY); Newark Museum (NJ); Legacy Museum, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, AL; and Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY).

[1] Richard J. Powell, “‘In My Family of Primitiveness and Tradition’: William H. Johnson's ‘Jesus and the Three Marys,’”American Art, v.5, n.4 (Autumn, 1991), 21.

[2] Shlomo Levy, “William H. Johnson” Henry Louis Gates and Evelyn Brooks Higgenbotham, eds., African American Lives (Oxford University Press, 2004), 305.

[5] Powell, “‘In My Family of Primitiveness and Tradition,’” 25.

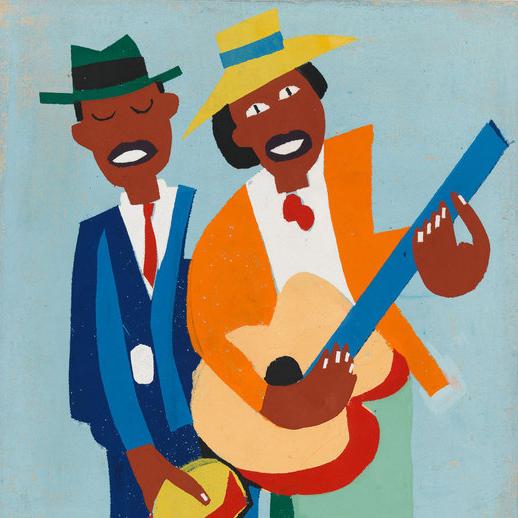

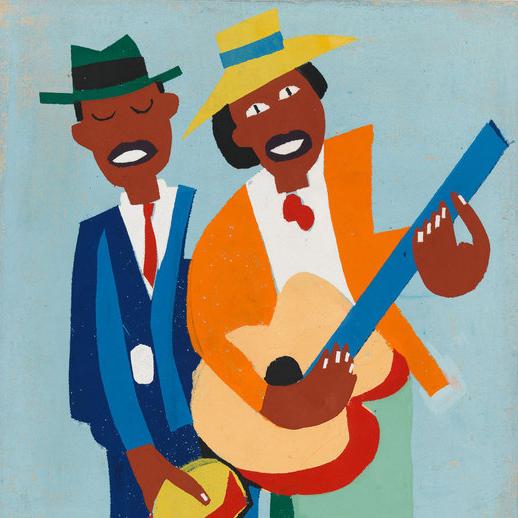

William H. Johnson (1901-1970), Blind Singer (detail), c.1940, pochoir on paper, 17 1/2" x 11 1/2"

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is proud to have placed this work in the permanent collection of The Whitney Museum of American Art. Johnson's Blind Singer was one of a select 58 works chosen for the Art Everwhere US campaign, as voted for by the American public.

The Art Everywhere US campaign is a public celebration of great American art exhibited on thousands of out of home (OOH) advertising displays across America. OOH advertising displays include billboards, bus shelters, subway posters, and much more.

Throughout the entire month of August, cherished American artworks will be seen by millions of people every day when they are commuting to work, taking the kids to school, hailing a taxi, shopping in a mall, catching a bus or pursuing other routine activities.

The movement for art to be seen everywhere is inspired by Art Everywhere founder, Richard Reed, who first produced Art Everywhere UK.

Five of America’s leading art museums have selected works of art that represent American history and culture. The American public has voted for their favorite artworks. The final selection of works are to be featured in the Art Everywhere US campaign, on display from August 4-31, 2014.