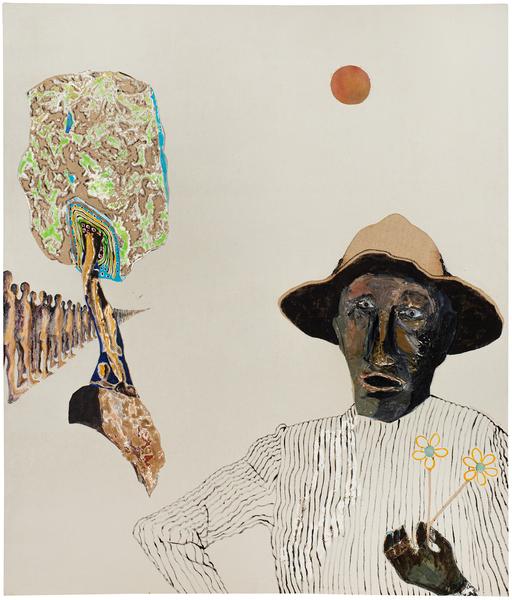

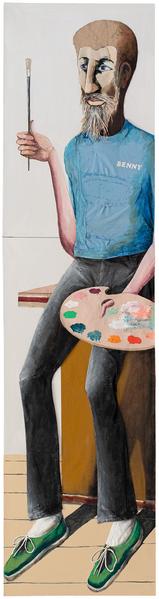

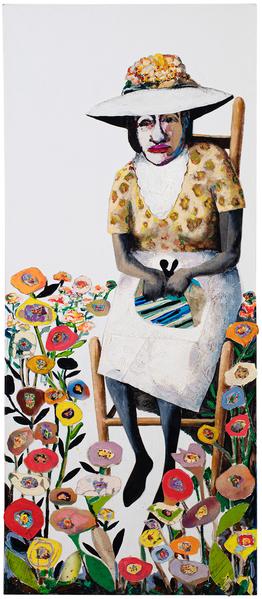

"I start out, I make a mess… I have to throw myself off so I don't copy what is right on top of my mind. Because if I just draw out or paint on something, I'm just copying what's in my mind. I'm trying to get deeper than that into my unconscious… I start out with a face and when I get a face that conveys a feeling to me of a real person, and I mean in feeling—I don't mean in realistic photographic likeness, but I mean feeling. When I get some that looks like a real face then I'm on my way… A cardboard person, no matter how real their surroundings are, [is] still cardboard. So, that's what I'm trying for... some kind of strength. Whatever it is depends on whatever I'm trying to say—happiness, love, all those kinds of things. But if I get a real person before the eyes, then I'm on my way.”[1] —Benny Andrews, 1968

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is pleased to present its third solo exhibition for Benny Andrews (American, 1930–2006), showcasing portraits—a vital and constant genre throughout the artist’s oeuvre. Benny Andrews: Portraits, A Real Person Before the Eyes will feature 35 portraits, represented by paintings and works on paper created between 1957 and 1998. The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully-illustrated color catalogue with new scholarship by Jessica Bell Brown, Associate Curator for Contemporary Art, The Baltimore Museum of Art; Connie H. Choi, Associate Curator, Permanent Collection, The Studio Museum in Harlem; and Kyle Williams, Director of the Andrews-Humphrey Family Foundation.

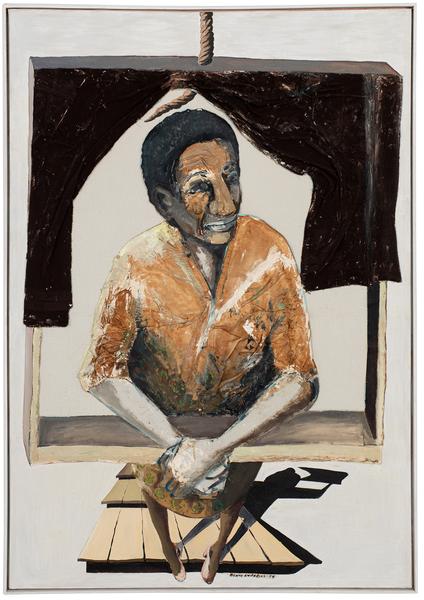

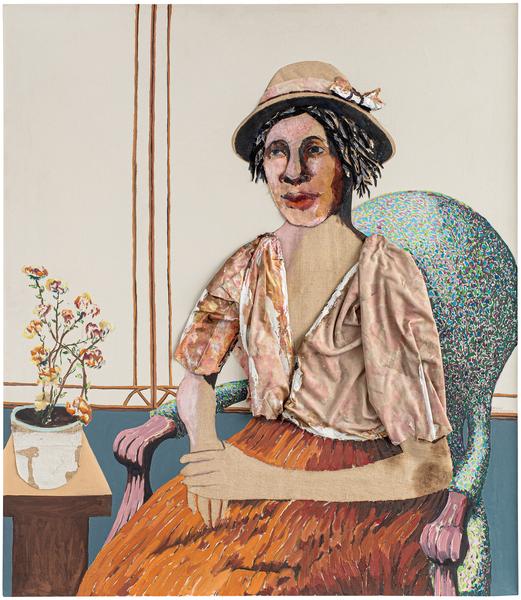

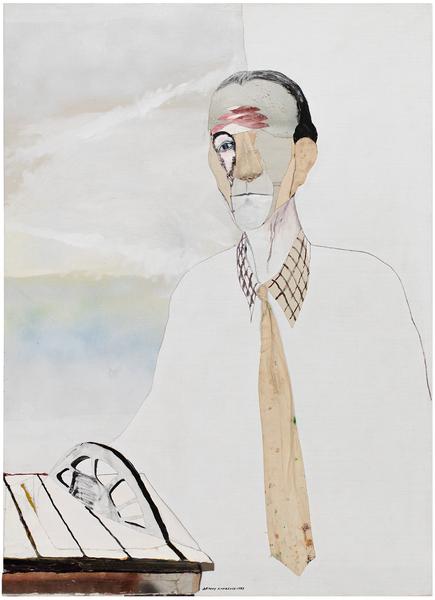

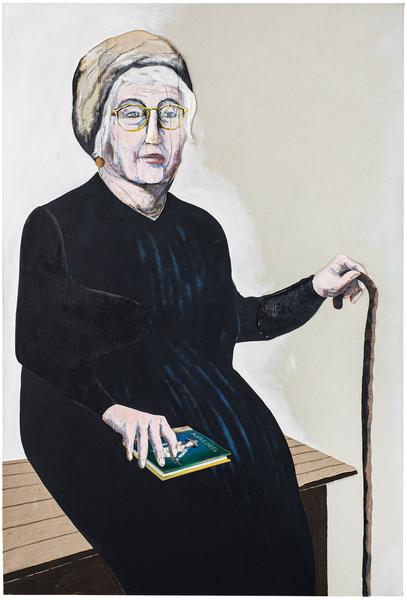

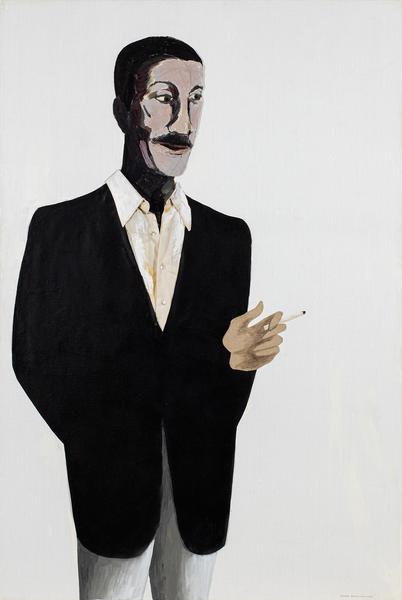

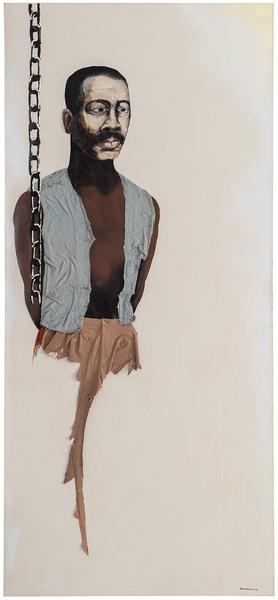

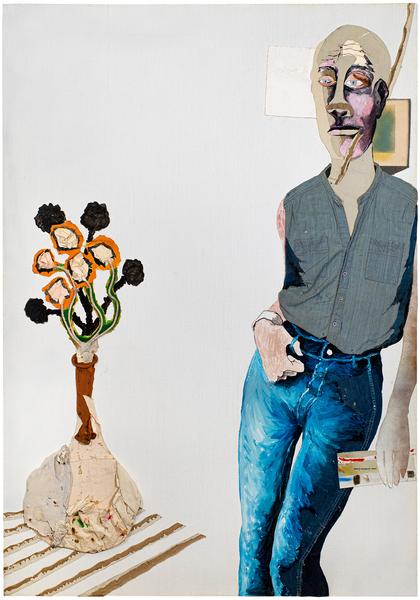

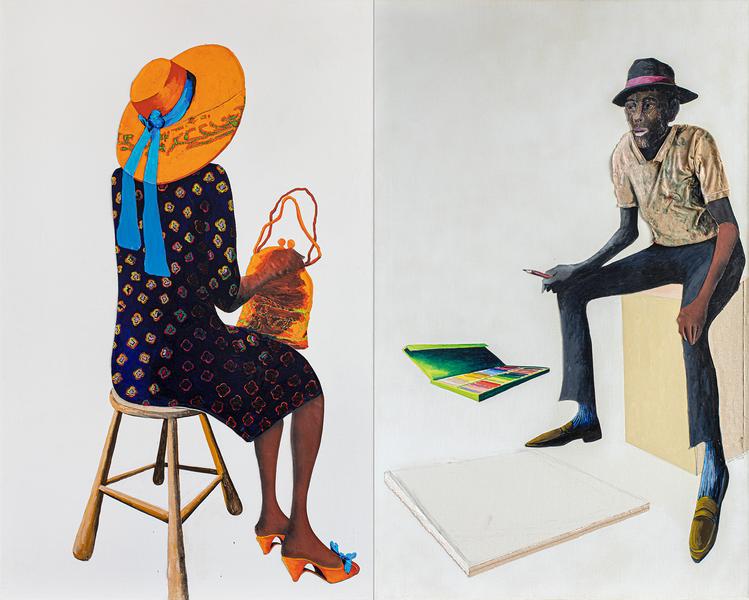

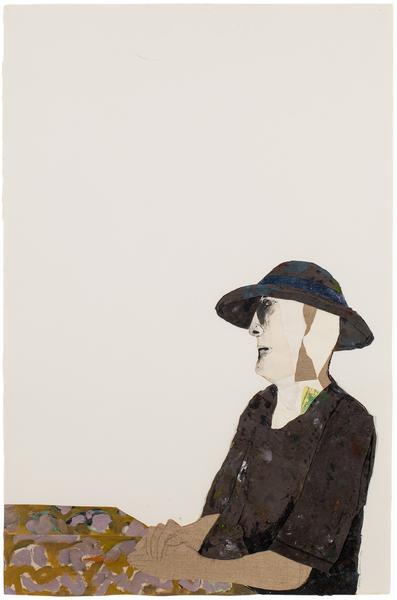

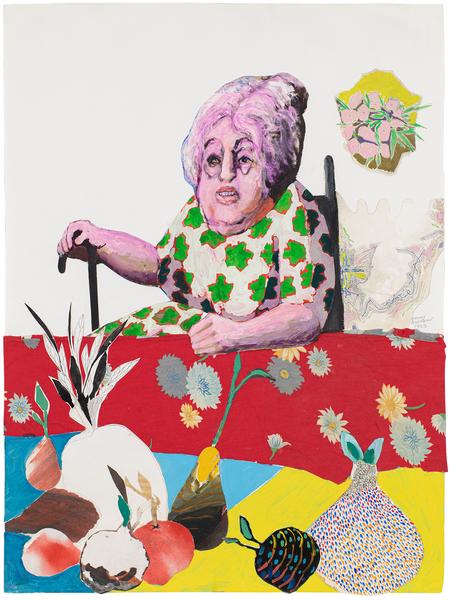

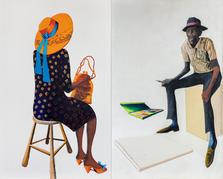

Benny Andrews: Portraits, A Real Person Before the Eyes traces Andrews’ commitment to portraiture, beginning in 1957 with Andrews’ seminal collage painting Janitors at Rest, and including portraits of fellow artists Marcel Duchamp, Ludvik Durchanek, Norman Lewis, Ray Johnson, Alice Neel, and Howardena Pindell, and also of his father George C. Andrews, and wife, Nene Humphrey. While Andrews created portraits of people he knew, as well as of himself, portraiture also served as a vehicle through which he could metaphorically express the personification of ideas, thoughts, emotions and values.

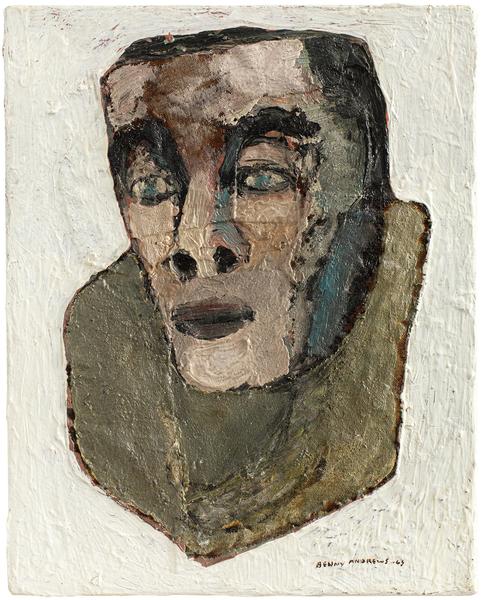

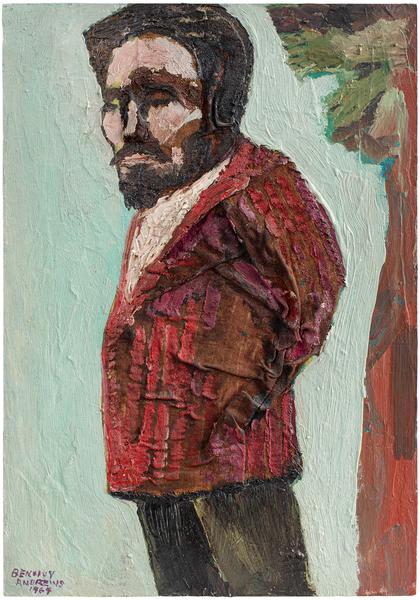

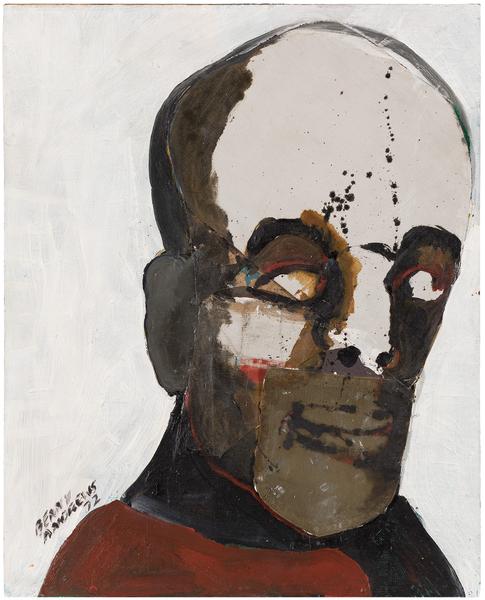

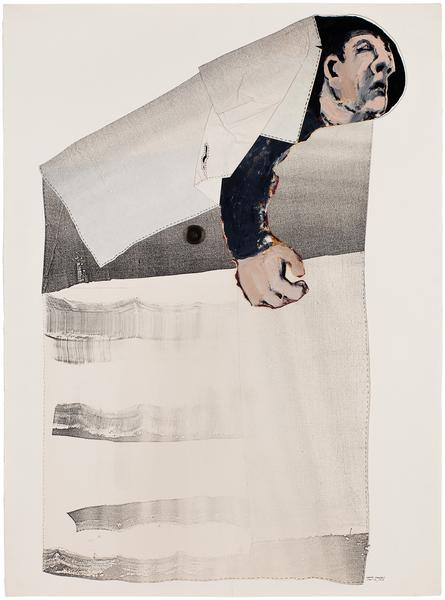

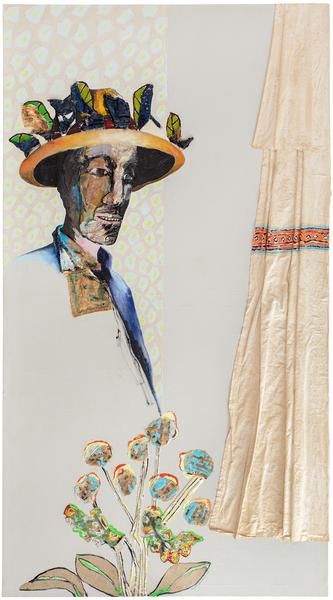

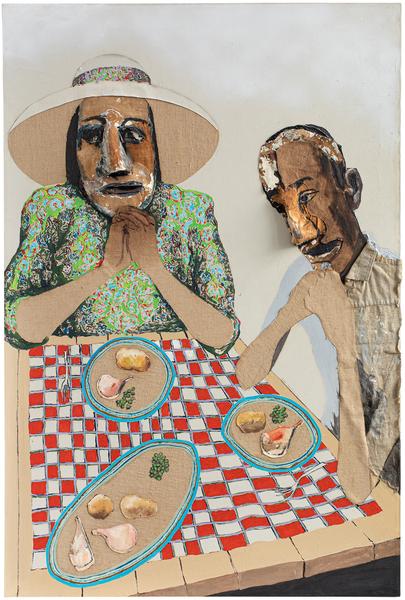

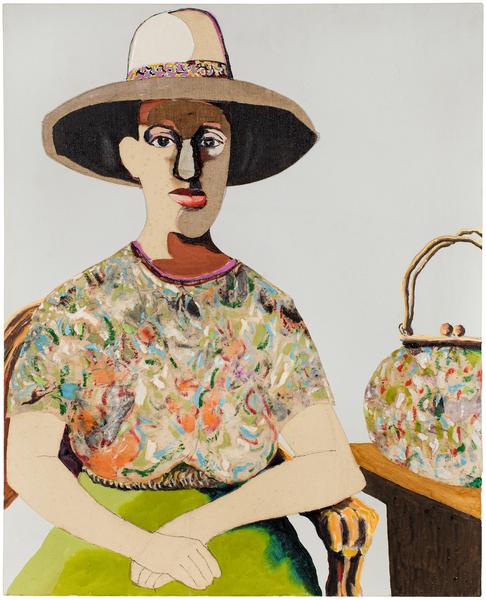

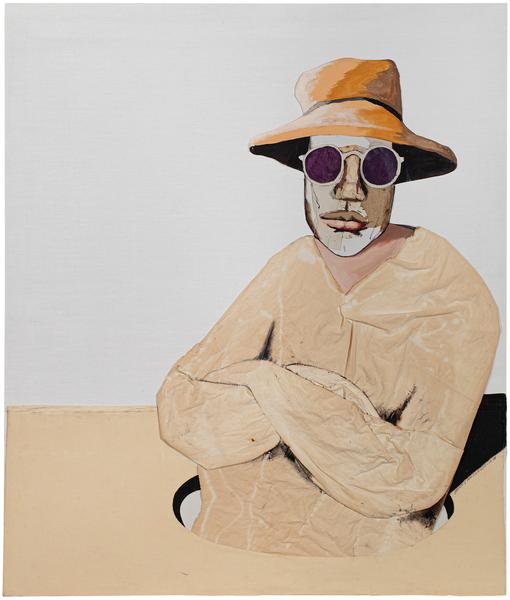

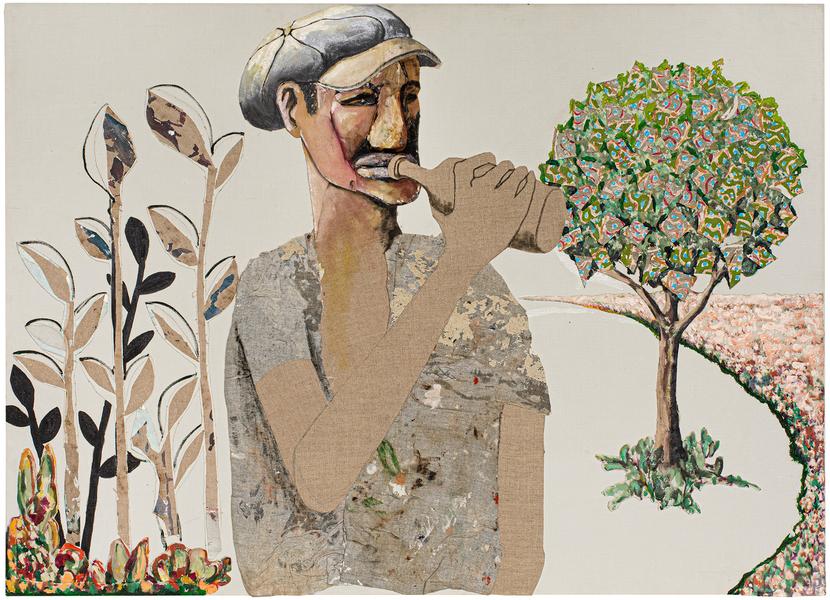

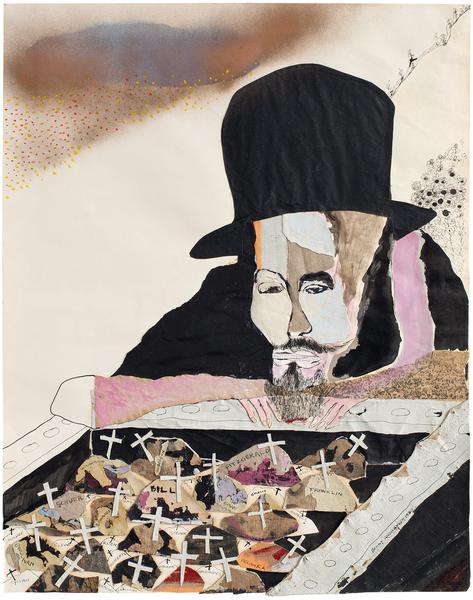

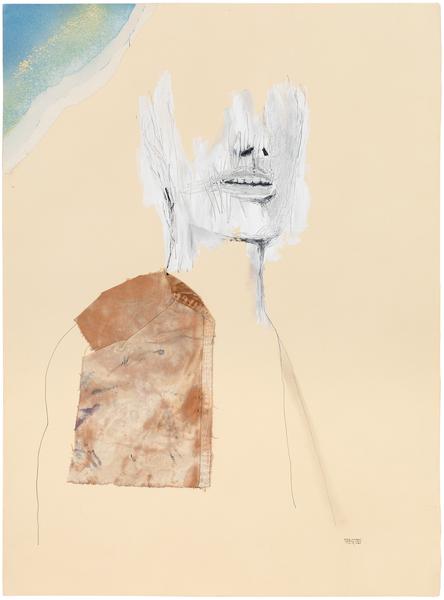

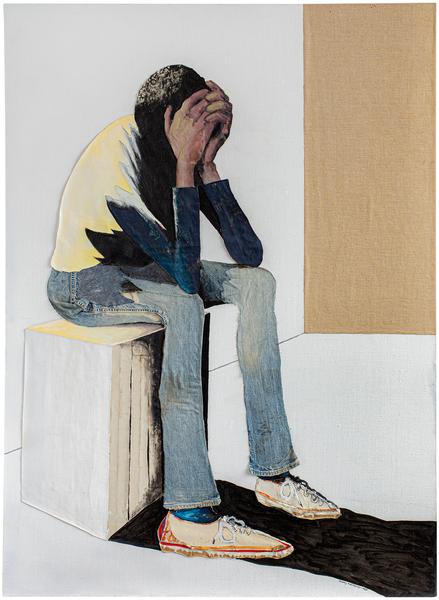

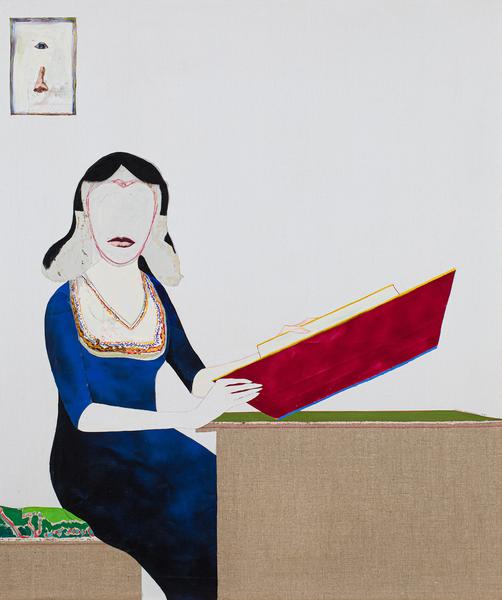

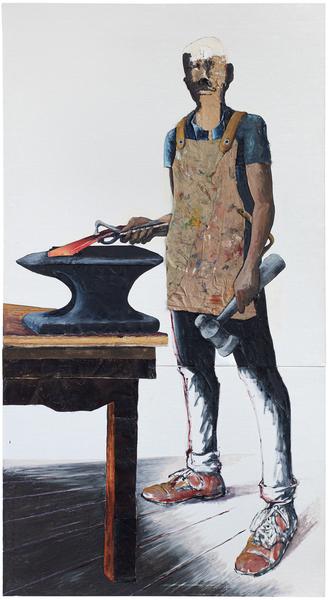

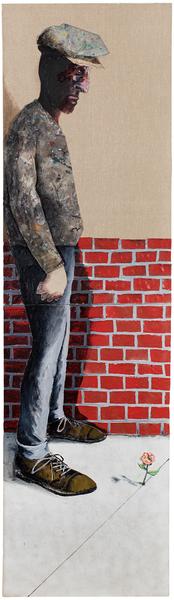

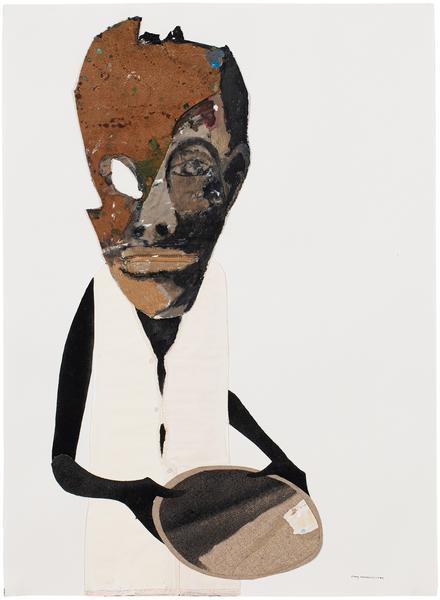

In his deeply humanizing portraits, Andrews employed his signature and pioneering use of paint and collage to build surface in order to create depictions composed of fleshy tactility, extending his sitters into three-dimensional space as a way of reinforcing their human presence and defining their distinct characteristics, since “collage provided him with a degree of depth and breadth not found in painterly realism.”[2] Indeed, his discovery of collage and texture was a way to construct surface in order to affirm his interest in both the individual and shared experience of humanity. His powerful depictions of people—both named and unnamed—reinforce his deep connection to the emotional soul of mankind.

Searching for a visual language to capture the immediacy of everyday life and the quotidian nature of his subject matter, Andrews first developed his “rough collage” technique, combining scraps of paper and cloth with oil paint on canvas, as a student. He honed this technique in a breakthrough period during his studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, when, in 1957, he was struck by the school’s African American janitors and created the pivotal Janitors at Rest, which first introduced collage into his painting. This critical component would inform the rest of his artistic career. The work—begun during his last year of school—became a turning point for him as he began to completely devote himself to painting. At the same time, he began studying with the painter Boris Margo (1902-1995), “the instructor who had encouraged him to paint what he knew, what he felt.”[3] Indeed, Andrews was inspired by the janitors and their environment, studying their faces and experimenting with their materials—like towels and toilet tissues. The artist wrote: