One might say that art, like science, is a constant probing of the unknown—a seeking. I believe an artist should make art that he feels relevant to his day, taking into account the works of artists of the past. The empty spaces within and around a sculpture pose a challenge that has become for me almost an obsession.[1]—Harold Cousins

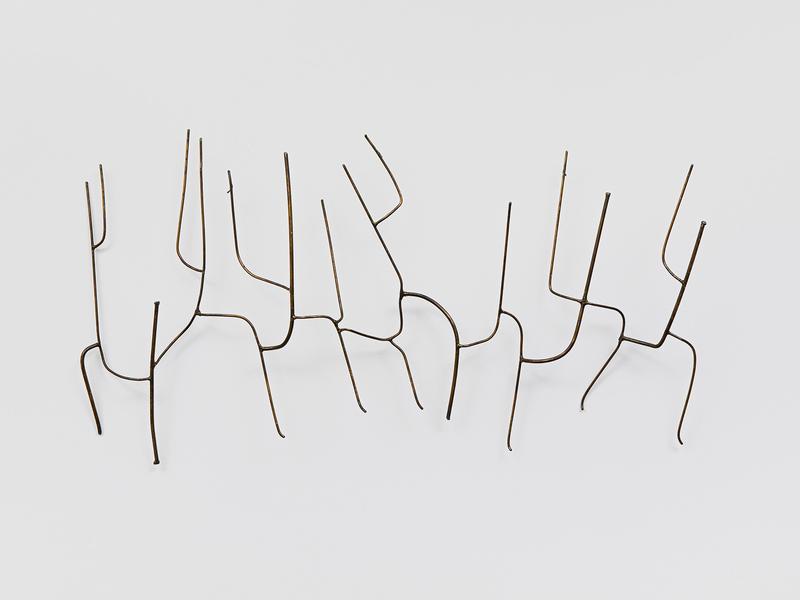

Whether forests, drawings in space, plaitons, or all the works in between, his sculpture… pulses with the imperfect, brittle dynamism of life. Cousins indeed created cathedrals that tremble, echoing across national boundaries and the passage of time, casting long shadows that speak to the miraculous, breathtaking ability of sculpture to reshape and re-envision space.[2]—Marin R. Sullivan

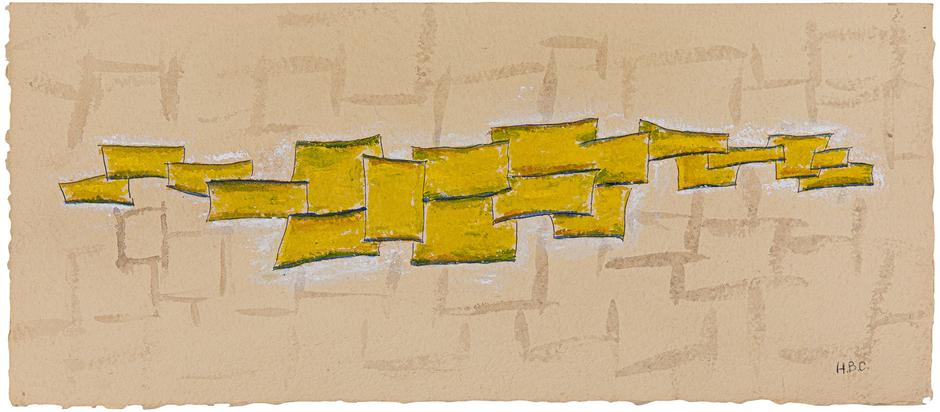

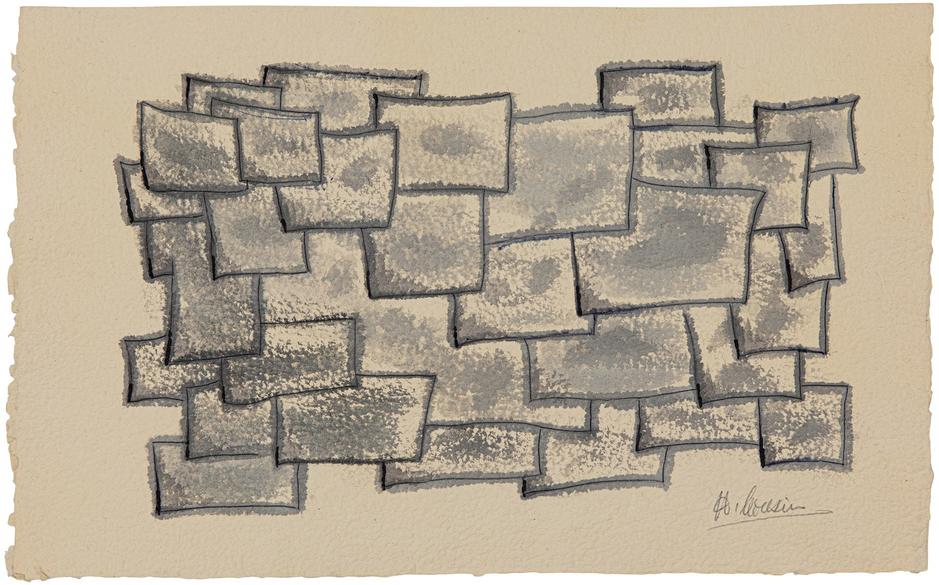

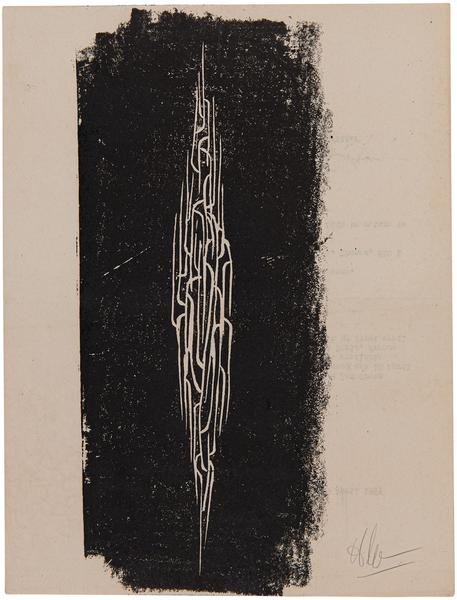

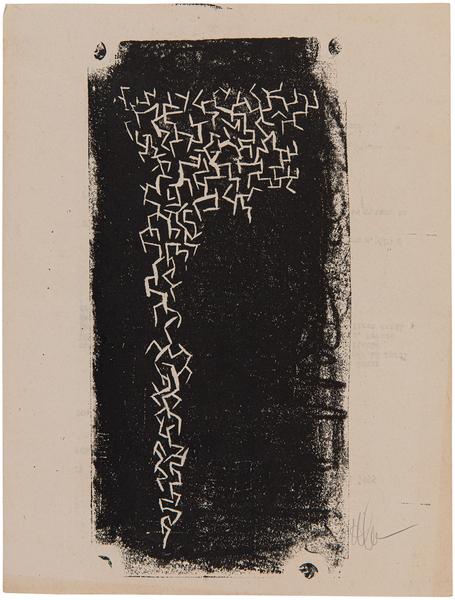

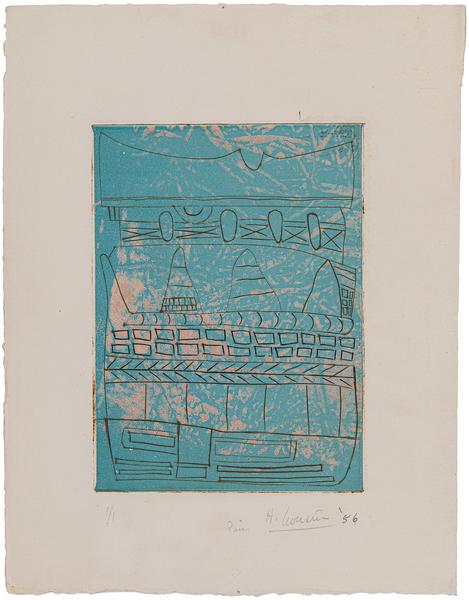

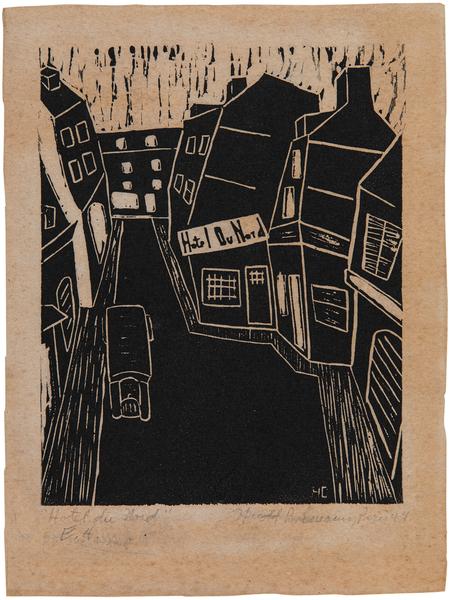

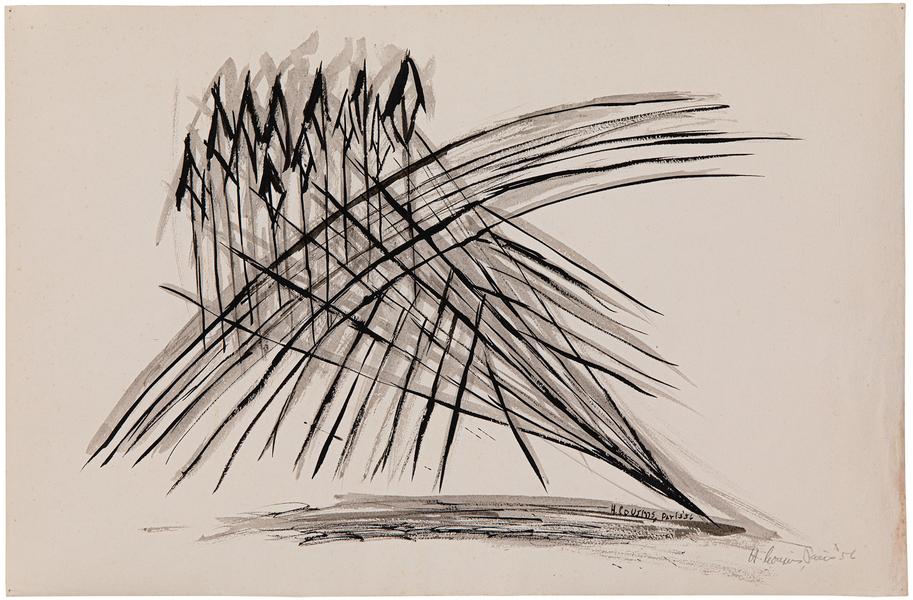

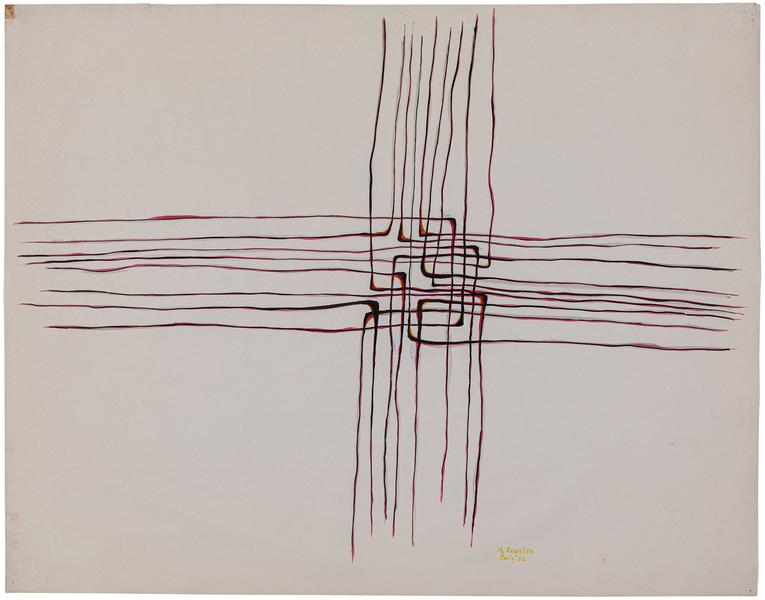

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is pleased to announce Harold Cousins: Forms of Empty Space, the first solo exhibition of the artist’s work in the United States in fifteen years. Comprising thirty metal sculptures executed between 1951 and 1975 as well as a group of related works on paper, the presentation is the gallery’s first exhibition dedicated to Harold Cousins (1916–1992) since taking on representation of the artist’s estate in 2020. Beginning with his first mature metal sculptures, Harold Cousins: Forms of Empty Space charts the formation and evolution of Cousins’ major sculpture series, including his forests, drawings in space, Gothic cathedrals, and plaiton works.

The inciting event for Cousins’ turn to metalworking occurred a few years after he moved from New York to Paris in 1949, where he joined a vibrant scene of fellow expatriate artists that included Ed Clarke, Beauford Delaney, Herbert Gentry, Loïs Mailou Jones, and others drawn to the exceptional stylistic freedom enjoyed by the city’s avant-garde. In Paris, Cousins was one of about ten students accepted to study sculpture at Ossip Zadkine’s studio, where he absorbed the irascible modernist’s lessons on sculpting in the round. However, it was another student at Zadkine’s studio, the American sculptor Shinkichi Tajiri, who would have a formative impact on Cousins’ early artistic development, when he taught Cousins how to weld with an oxyacetylene torch. Eager to learn more about metalworking, Cousins studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière from 1951–52; it was also around this time that Cousins discovered the work of Spanish metalsmith-turned-sculptor Julio González, an artist he came to revere as one of the greats of his era and whose work he cited as a primary source of inspiration for his initial foray into direct-metal sculpting.

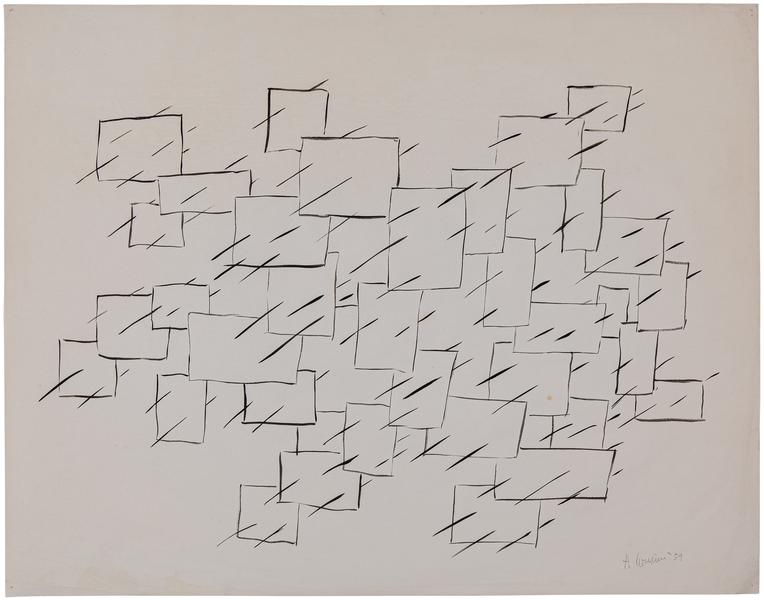

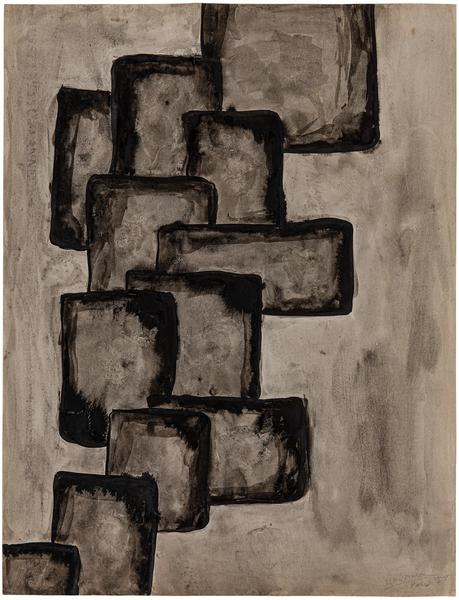

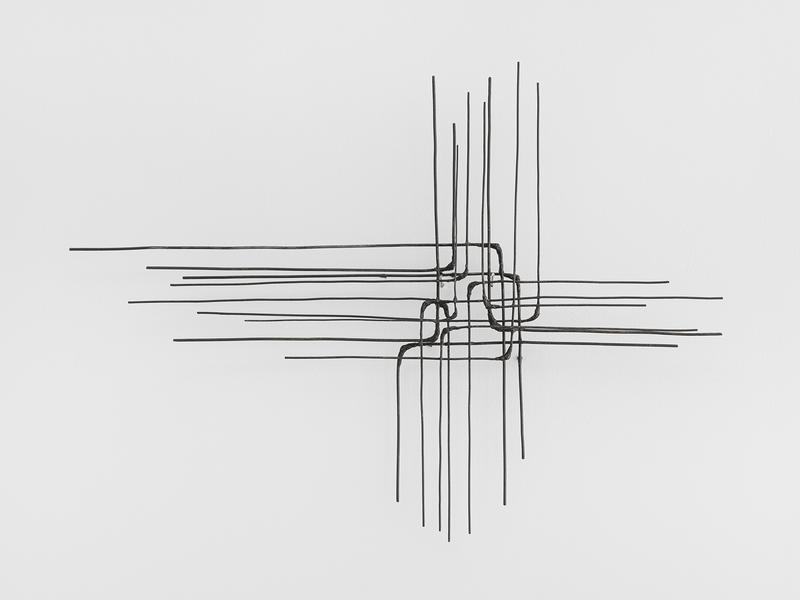

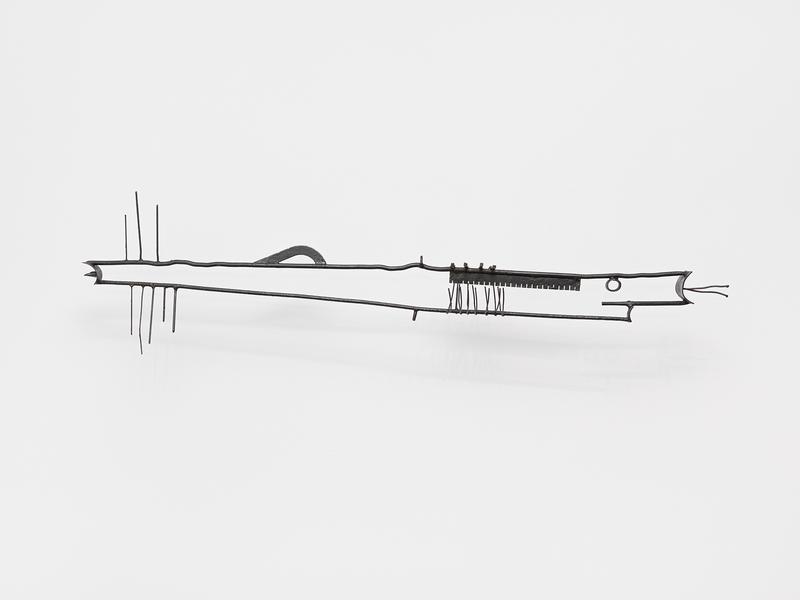

It was in this environment of artistic enrichment and discovery that Cousins developed what would become one of the guiding conceits of his mature sculpture practice, namely a consideration of the negative space surrounding the sculpture as equal to that of its material components—in other words, he came to regard space as a compositional element. While his formal education and social network had provided him with the skills necessary to explore this avenue of thought, it was Cousins’ deep engagement with the art of past cultures that brought about this key stylistic breakthrough. During these early years in Paris, he frequented the Musée Rodin, the Musée de l'Homme, and the Louvre, studying Rodin’s Monument to Balzac (1892–1897) and sketching certain artifacts from ancient Egypt and 19th-century Hawaii, particularly the latter culture’s human-hair-and-whale-tooth pendants known as lei niho palaoa. Contemplating the formal qualities that drew him to these works, Cousins explained: “[They] possessed the same basic quality: they gave one the visual impression of something existing that was not present in the forms of their material parts. I became convinced that this ‘something’ was the form of the empty space between the parts of a sculpture or around a solid.”[3] The artist thus developed his own personal gestalt theory, in which the suggestion of form within or around a sculpture is tantamount to its overall structure, and that the evocative thrust of the artwork derives from the interaction between the two.

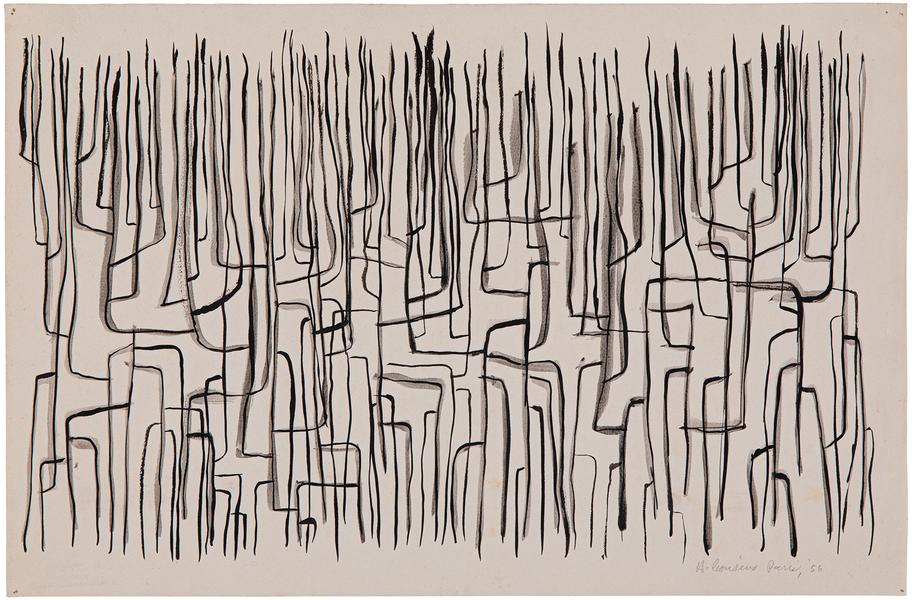

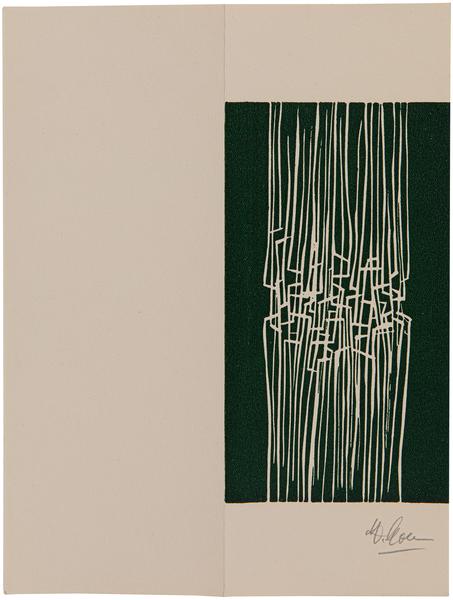

Harold Cousins: Forms of Empty Space will feature several highlights from Cousins’ first decade in Europe, surveying the artist’s seemingly endless experiments with the foundational formal elements of line, plane, and texture. While clearly grounded in abstraction, Cousins’ sculptures from these years often reference specific subjects, including grand classical themes such as warriors and saints, botanical and animalic organisms, quotidian encounters such as musicians and dancers, and self-referential meditations on modernism, such as an homage to the neoplastic master Piet Mondrian. Describing his method for these works with a term coined by González—"drawing in space”—Cousins sought to activate the area around and within his sculpture, just as a draftsman would animate their paper through the delineation of positive and negative space. Composed with an emphasis on their linear elements, the artist executed these sculptures with a particular consideration of the interplay of light and shadow created by the works’ forms and varying degrees of transparency. As art historian Robert Slifkin posits in his recent survey of postwar sculpture, “Welded sculpture’s airy openness made its existence in actual space crucial to its visual appearance. The world, one could say, appeared within the work, just as its decidedly nonartistic materials and methods of assembly made it strikingly of the world.”[4]