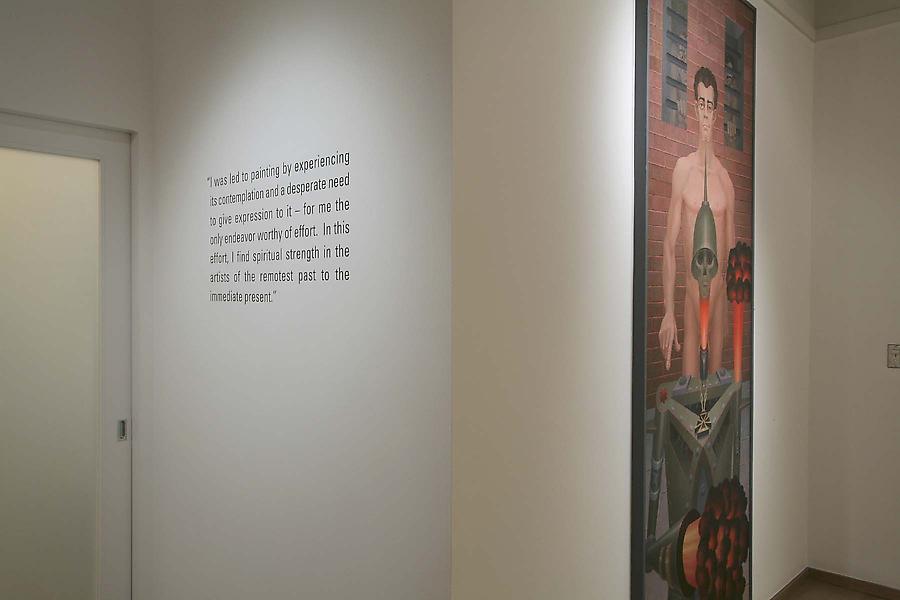

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is now the exclusive representative of Irving Norman (1906–1989) and in its first presentation of this California painter, will present a selection of paintings and drawings from the 1940s to the 1980s. Known as a social surrealist for his large-scale, detailed critiques of contemporary life, Norman painted with a dark vision at once personal and prophetic. He believed that by pointing out the inequities, horrors, and foibles of human behavior he might somehow cause people to consider the consequences of their actions and ultimately, change. Painted in jewel-tone colors, Norman's massive canvases abound with teeming figures — drone-like and mechanical in their repetition, yet stubbornly and hauntingly human.

Born Irving Noachowitz in Vilnius, Lithuania in 1906 (when the capital city was called Vilna and fell under Russia’s control), Irving Norman emigrated to the United States in 1923, settling first on New York’s Lower East Side and then upstate in Monticello, where he trained as a barber. In the United States, Norman was strongly influenced by the leftist thought that flourished under the dire economic conditions of the Great Depression: “It taught me not to be so self-centered, but to be concerned about the world...to be aware of the connection of your personal life with the world. I became conscious of what happens to people globally.” (1) This education partly motivated his decision to leave the home and barber shop he had set up in 1934 in Los Angeles and to join the Abraham Lincoln Battalion of the International Brigade, formed to help defend the Spanish Republic from the encroaching fascist dictatorship of General Francisco Franco. Although Norman did not expect to survive the Spanish Civil War, he did, and in 1939, he returned to California, settling on Catalina Island, where he began to express through drawing and painting the atrocities he had just witnessed. As he later explained, “My war experience taught me about the oppressiveness of the power structure in its extreme form. At this stage in human development it struck me as a horrible irony that all of the best in science and technology was directed towards destroying people. I wanted to have something to say about this. I turned to art...I discovered my medium slowly.” (2)

In 1940, Norman moved to San Francisco and enrolled in classes at the California School of Fine Arts. He quickly excelled, receiving a solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1942 and winning the 1945 Albert Bender Memorial Prize of the San Francisco Art Association (SFAA). The prize money enabled him to travel to Mexico City in 1946, where he saw the vibrant, populist murals of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. From Mexico, Norman headed to New York City, studying at the Art Students League from 1946 to 1947.

When Norman returned to San Francisco at the end of the 1940s, he settled in Lagunitas and exhibited his watercolor Slums in the SFAA’s 13th Annual Color Exhibition (1949). Although one critic described it as “The outstanding painting of the exhibition...an amazingly convincing representation of the crowded, poverty stricken and degrading life in the slums of a large city,” (3) such acclaim did not protect Norman from censorship by the SFAA the following year. In 1950, the organization removed his Big City from an exhibition at the de Young Museum because of eight, small, allegorical scenes depicting prostitution. Described by SFAA president as “a little bit crude” and “too raw,” Big City became the first painting banned from the de Young on charges of obscenity.

October 30 – December 20, 2008

Artists

Press

Publications

Press Release

Despite the scandal, Norman continued to receive critical praise and support for his work throughout his long and staunchly independent career. In 1957, Rush Hour, inspired by his experiences of the teeming subways of New York and other major cities, was included in the Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture biennial at the College of Fine and Applied Arts of the University of Illinois, Urbana. Two years later, Irving Norman was mounted at the Designer’s Gallery, San Francisco, and in 1970, the Brooklyn campus of Long Island University held a retrospective of the artist’s career. Finally, in 1996, forty-six years after it banned Norman’s work and seven years after the artist’s death, the de Young recognized Norman’s talent with a retrospective.

Norman’s experience as a Polish-Jewish immigrant helped to shape his understanding of American society, and he often seemed to observe life in the United States with the shrewd and detached eye of an outsider. Over the course of his long career, Norman became best known for his highly detailed paintings, which offered powerful critiques of inhumanity and social injustice. He believed that by pointing out the cruelty, economic oppression, racism, and brutality enacted by individuals as well as governments, viewers of his work might be moved to change society or at least to consider their own role in larger systems of power. Influenced in spirit and style by Rivera, Orozco, and Siquieros, Norman intended his own paintings to be public art. Therefore, he shunned private patronage – often to his own financial detriment – and avoided commercial viability. Instead, the artist expressed the wish that his work be placed in public institutions, particularly museums, where “all people could come and study them and contemplate.”

Norman saw everything in human terms. His paintings are monumental in scale, yet they teem with detail, populated by swarming, anonymous, clone-like figures. These generic signifiers of humanness are usually constricted by small urban spaces, caught in the crunch of rush hour, decimated by the pain of poverty, destroyed by the horror of war, trapped by the excesses of global capitalism. Such themes manifest Norman’s perception of modern life and the society in which he lived, and his critiques of injustice are often animated by the artist’s dynamic, off-kilter compositions, jewel-like colors, and piercing wit. Once engaged, the viewer cannot ignore or forget Norman’s unsettling visions.

Always uniquely his own, Norman’s paintings are nonetheless informed by a broad knowledge of art history, and they reveal the influence of numerous artists, cultures, and art movements. During decades overshadowed by pure abstraction, Norman focused on carefully detailed representational imagery and strong social messages. His choice to buck dominant artistic trends makes his work difficult to fit neatly into a historical schema. But this and even the fact a 1988 fire destroyed his home, studio, artwork, and personal papers, only partially account for his marginalization in American art history. Much of Norman’s earlier obscurity also stemmed from twenty years of surveillance by the FBI. Norman’s political affiliations and especially his service in the Spanish Civil War (ironically, against a fascist dictator aligned with Hitler and Mussolini) marked him as a target for McCarthyist attacks on left-leaning intellectuals. However chilling the effect of such government scrutiny upon his art and life, Norman’s paintings stand as a testimony to his talent, determination, unfaltering conscience, and to his ultimate belief in humanity. While often horrific and terrifying, Norman’s colossal works contain a deeper message, one of hope.

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC is the exclusive representative of the Estate of Irving Norman.

To view this exhibition in its entirety online, please visit www.michaelrosenfeldart.com

Visuals available upon request.

For additional information, please contact Marjorie Van Cura at 212.247.0082 or mv@michaelrosenfeldart.com