“I have always believed in the human capacity to persevere and overcome the most incredible circumstances.”[1]

Known for his detailed paintings protesting inhumanity, Irving Norman was born Irving Noachowitz in 1906 in Vilna, which at the time was under Russia’s control. In 1923, he emigrated to the United States, settling on New York’s Lower East Side, where he trained as a barber, and then moving to Laguna Beach, California, where he opened his own barber shop in 1934. In 1938, Norman joined the Abraham Lincoln battalion of the International Brigade to help defend the Spanish Republic from the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco. After the war, Norman returned to California transformed by his experience. Searching for a way to express the atrocities he witnessed in Spain, Norman turned to art. He moved to San Francisco in 1940 and enrolled in classes at the California School of Fine Arts, where he excelled. By 1942, Norman had a solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art. In 1946, he went to New York City and studied with Reginald Marsh and Robert Beverley Hale at the Art Students League before traveling to Mexico to see the murals of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. In the late 1940s, Norman returned to the San Francisco Bay Area.

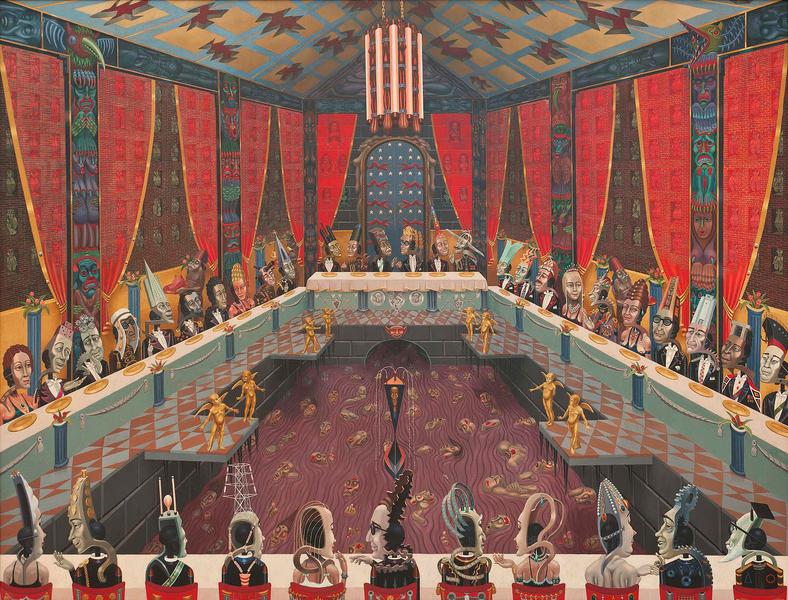

The muralists had a profound influence on Norman in spirit and style. Working extensively in watercolor, he expanded the medium’s size to monumental proportions. But while he painted on a grand scale, he saw in human terms. In massive works teeming with detail, populated by swarming, anonymous, often nude, clone-like figures, Norman railed against injustice and captured the chaotic alienation of modernity. His forms, generic signifiers of humanness, are constricted by small urban spaces, caught in the crunch of rush hour, decimated by the pain of poverty, destroyed by the horror of war, and trapped by the excesses of global capitalism. Such themes reveal Norman’s perception of the society in which he lived and were animated by dynamic, off-kilter compositions, jewel-like colors, and piercing wit. Norman believed that by bearing witness to cruelty and oppression in his paintings, he might move his viewers to consider their own role in systems of power. In light of that aspiration, he intended his paintings to be public art, placed in institutions accessible to all. He eschewed commercial viability and avoided private patronage.

Norman’s success as a painter during his lifetime seems modest when compared to the celebrity of his abstractionist contemporaries. In the 1950s, his reputation began to rise, despite the decade’s opening with his watercolor Big City being banned from an exhibition at the De Young Museum in San Francisco on the grounds of obscenity. In the remainder of the decade, Norman’s work was included in several major exhibitions, including a 1953 show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture Biennial at the University of Illinois, Urbana (1957). In 1964, his drawing War and Peace was shown as part of the San Francisco Art Association exhibition at the city’s Art Institute, where it received considerable attention. In the 1970s and 1980s, Norman was the subject of several solo exhibitions at commercial and university art galleries, but widespread success eluded him.