Opening Reception: Saturday, September 10, 2022, 6–8PM

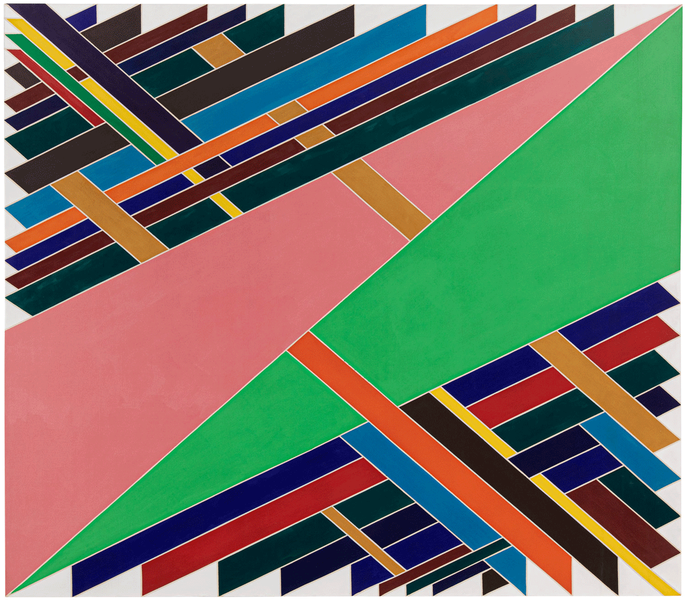

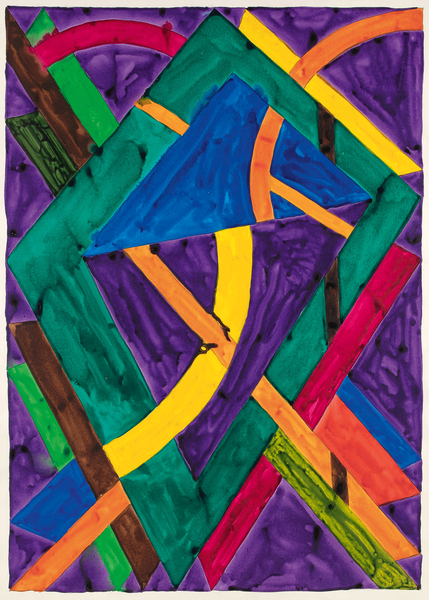

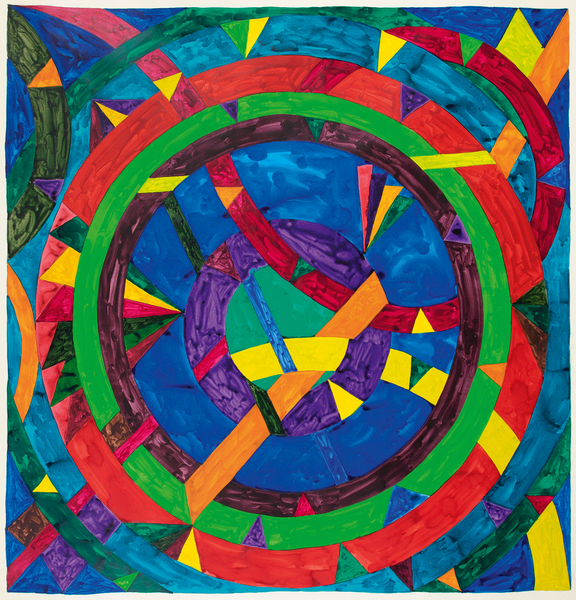

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery proudly presents Tension to the Edge, its third solo exhibition featuring the work of William T. Williams (b.1942). On view from September 8 through November 5, 2022, the exhibition focuses on the artist’s large-scale abstract paintings created between 1968 and 1970 as well as a related group of works on paper from the same period. Created during an era of significant social, political, and personal turmoil, the works on view in William T. Williams: Tension to the Edge address the upheavals of their moment through Williams’ distinctive language of hard-edged abstraction. The centerpiece of the exhibition is a stunning selection of five wall-sized paintings, four of which have not been seen since 1969; though they were painted nearly fifty years ago, Williams’ singular treatment of form, surface, and color render these works as fresh and groundbreaking as they were at the time of their creation.

“The paintings that I was doing in the late 1960s had a number of devices that I thought spoke to [the political climate of the time],” Williams states. “The paintings were contained. I never allowed forms to go off the edges—I wanted this sense of containment and suppression. …I've said from the very beginning that my work is autobiographical: it speaks to those experiences that I've had as a human being but also more specifically as a Black human being. The work has always been about that.” [1]

The paintings featured in Tension to the Edge constitute the genesis of the “diamond-in-a-box” motif that would become a formal and thematic continuum in the artist’s oeuvre. Williams has referred to the diamond-in-a-box device as a “stabilizing force” that structures the chaos he sought to convey within these works—a reflection of the tumultuous conditions of the era.

While their monumental scale and meticulously sharp lines situate Williams’ paintings in conversation with the ascendant minimalist painters of the decade, the artist’s self-contained, architectural approach to composition, masterfully nuanced textures, and complexly interlocking geometries set them apart from contemporaneous trends in nonobjective painting. Perhaps the most important difference between Williams and his minimalist contemporaries is Williams’ prevailing concern with conveying specific personal or spiritual qualities in his work. His paintings exist as a composite of collective or individual memories and auratic impressions; the artist cites church services and family outings to the Apollo theater in Harlem as experiences that shaped his early conceptions of “presence,” that is, a site where spiritual expression and the physical environment coalesce. The chaotic barrage of light and color that characterizes the environment of the Far Rockaway waterfront was also a primary source of inspiration for the chromatic relationships in these works, evoking a kaleidoscopic impulse that dovetailed with his abiding interest in the Fauves. The bodily relationship between painting and viewer has likewise been an enduring concern in Williams’ art, and the works in Tension to the Edge demonstrate his earliest mature efforts in creating paintings with a clear physical power, embodying, in his words, “place as a specific type of poetry.”

The intentionally discordant, complexly juxtaposed palettes of the paintings in Tension to the Edge testify to Williams’ status as the foremost colorist of his generation. The artist was especially interested in the potential for certain colors and chromatic contrasts to evoke a specific emotional response and deliberately avoided the harmonic arrangement of complementary hues, boldly undermining the established principles of color theory. The artist often embraced conflicts between his paintings’ formal structure and their palette, finding the resulting “dissonance” an apt metaphor for the sociopolitical conditions of the times. Eliding the eye’s transition from one color to another within each work are the cleanly demarcated lines of unpainted canvas—an effect produced by Williams’ assiduous use of tape, which he applied to ensure the pigments lay alongside each other, rather than blending at the edges. Thus, whatever effects arise from his colors’ interaction is a phenomenon that occurs within the mind’s eye (rather than on the canvas itself).

Working out of his newly leased loft on Broadway and Bond Street—where he continues to work today—Williams sketched the composition of each work directly onto the canvas with a pencil and straightedge, using the diamond form as a starting place. Williams allowed his intuition to guide the compositional process, making no erasures or revisions to his layout before moving the canvas from the floor to the wall or a roller bridge for painting. The individual planar forms of each composition thus exist as iterative elements of the foundational diamond shape, much like the rhythmic improvisations of a jazz musician riffing on a standard theme. Indeed, jazz has remained a primary source of inspiration for Williams throughout his career, and his studio was located just blocks from the city’s vanguard jazz clubs at the time. The paintings on view in Tension to the Edge further reflect important painterly influences that would shape the evolution of Williams’ style, namely the hard-edge abstractions of Al Held (Williams’ graduate instructor at Yale), the minimalist paintings of Kenneth Noland (whose studio was one floor below Williams’), and the fauvist works of Henri Matisse.