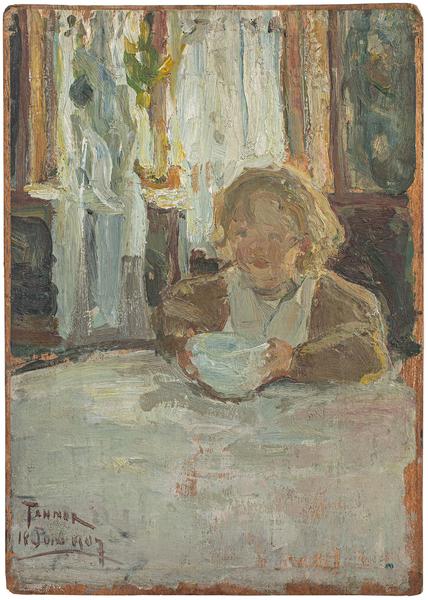

“I choose my religious subjects not primarily because I believe they will interest people, nor because I consider them most salable . . . I have chosen the character of my art because it conveys my message and tells what I want to tell to my own generation and leave to the future.”[i]

Canonized as the patriarch of African American artists, Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) stands as the most significant African American artist of the nineteenth century and the first to achieve international fame. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1859 to Benjamin Tucker Tanner, an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) bishop, and Sarah Miller Tanner, a former slave who had escaped through the Underground Railroad, Tanner spent much of his childhood moving between Alexandria, Virginia; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Frederick, Maryland, where they lived during the last year of the Civil War. When Tanner was thirteen, his family returned to Philadelphia to settle permanently. Soon after, Tanner saw a man painting landscapes in a Philadelphia park and knew he wanted to become an artist. The next morning, Tanner purchased art supplies and began his first attempts at sketching and painting. While Benjamin Tanner had no objection to art as a pastime, he discouraged his son from becoming a professional artist. However, despite his father’s objections, in the fall of 1879, Tanner attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied with Thomas Eakins until 1882. Although he left school early, Tanner continued to paint, and he attempted to make a living as an artist. In 1888, he set up a photography studio in Atlanta, Georgia, where he also sold drawings and taught art classes. However, the studio proved untenable as a real source of income. Tanner closed the studio and spent two years teaching art at Clark College in Atlanta.

In 1891, Tanner traveled to Europe initially intending to study in Rome. Instead, he went to Paris, where he studied at the Académie Julian with Jean Joseph Benjamin-Constant and Jean-Paul Laurens. In 1892, Tanner returned to the United States for two years, settling in Philadelphia. During this time, he painted two of his most celebrated genre scenes of African American subjects, The Banjo Lesson (1893)—which was inspired by Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem A Banjo Song—and The Thankful Poor (1894). Tanner’s relative privilege as a child had not protected him from racism, and an astute observer, he saw how his father was treated differently even by fellow clergymen due to the color of his skin. As an adult, Tanner became increasingly convinced that racism in the United States would prevent his work from gaining the recognition it deserved, and in 1894, just two years after Homer Plessy was arrested for sitting in a “whites only” train compartment in Louisiana, Tanner left the home he loved for Paris, settling there permanently.

Tanner’s move to Paris coincided with a rise in religious painting, due in part to a Catholic revival in France as well as to the sacred imagery prominent in the work of the symbolists. In 1895, Tanner also began to create paintings based on religious themes, and while his work might have overlapped in theme with that of his contemporaries, Tanner’s style, in particular his ability to capture both the ethereal and the material on canvas, owed more to art of the past. In 1896, Tanner’s Daniel in the Lion’s Den received an honorable mention at the Paris Salon, and the following year, Resurrection of Lazarus won a medal and was subsequently purchased by the French government.