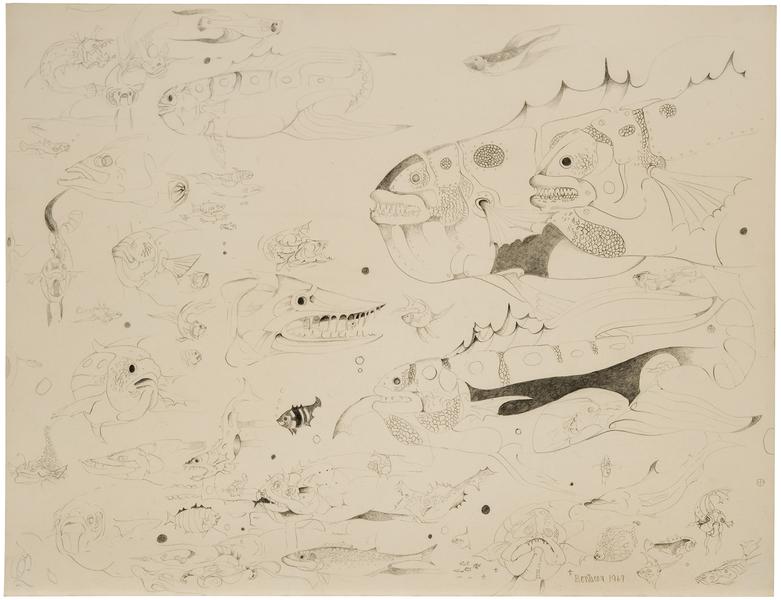

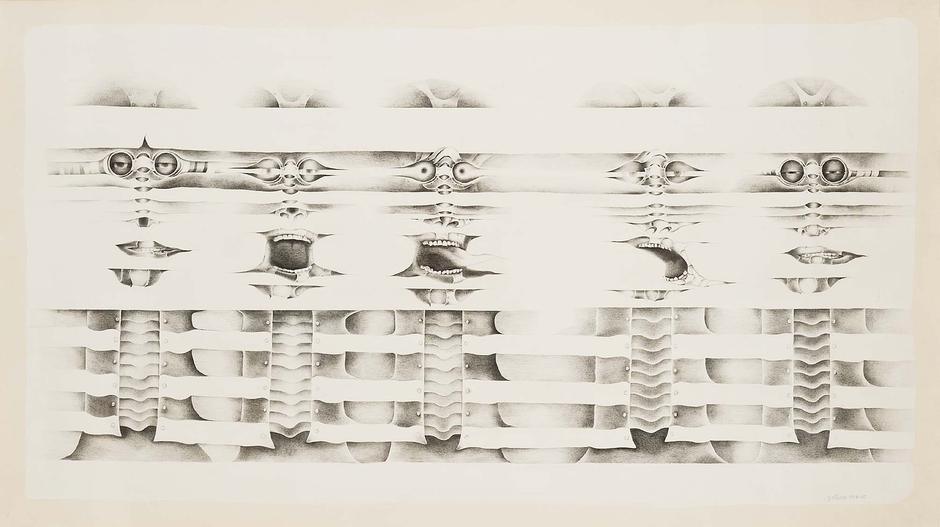

“My most persistently recurring thought is to work in a scope as far-reaching as possible; to express a feeling of freedom in all its necessary ramifications – its awe, beauty, magnitude, horror and baseness. This feeling embraces ancient, present and future worlds: from caves to jet engines, landscapes to outer space, from visible nature to the inner eye, all encompassed in cohesive works of my inner world. This total freedom is essential."[i]

Celebrated for her wall-mounted assemblages and refined drawings of organic, otherworldly forms, Lee Bontecou (1931–2022) first rose to prominence in downtown New York’s midcentury avant-garde scene. Her enigmatic landscapes of imagined cosmic outer and inner worlds are augmented by her innovative use of materials—soot and found textiles primary among them—which accentuate the subtle yet incisive political critique inherent to her imagery.

Born in 1931, Bontecou grew up in Providence, Rhode Island, where her mother worked in a factory wiring submarine parts during World War II. The circumstances of her mother’s vocation combined with news reports about the war and the Holocaust had a formative effect on the young artist’s understanding of the sociopolitical climate of the 20th century. The artist’s preoccupation with world events continues to this day, and her work often demonstrates a sharp awareness of the horrors of war and social injustice. As a child, Bontecou also developed her life-long love of nature, particularly marine biology—an interest rooted in the many summers she spent in Nova Scotia, in her mother’s native Canada.

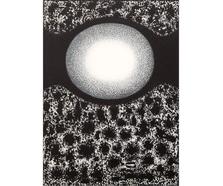

From 1953 to 1958, Bontecou attended the Art Students League in New York, studying with William Zorach and George Grosz, among others. In 1954, she learned to weld, during a summer course in Skowhegan, Maine. Two years later, she was awarded a Fulbright scholarship, which she used to study in Italy from 1956 to 1957. There she devised a novel drawing technique using an acetylene torch. Turning down the torch’s oxygen, Bontecou conceived what she called “worldscapes”: soot drawings in which “velvety black forms graduate slowly and atmospherically toward a horizon,” foreshadowing, as Mona Hadler points out, “Bontecou’s arresting amalgamations of two-and three-dimensional elements."[ii] Bontecou returned to New York in 1958 and began to translate the formal ideas expressed these drawings into three dimensions, creating the large, raw, wall-mounted assemblages that often feature a central gaping black hole opening on to a black velvet backdrop; these images would become her most well-known motifs and marked the artists entrée to critical and commercial success.

Bontecou enjoyed a steady stream of accolades throughout the following decade, initiated by her first solo exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1960. A year later, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York purchased Untitled (1961), a large-scale relief fabricated from canvas, rope, and wire in which the central hole grimaces with “teeth” sourced from the blade of a band saw. That same year, her work was included in The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. By 1963, MoMA had also acquired one of her works, and that same year she was commissioned by the architect Philip Johnson to create a monumental sculpture—which remains her largest to date—for the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center, which opened the following year. Bontecou also participated in the São Paulo Bienal in 1963; and in 1964, she and Louise Bourgeois were the only two women chosen to represent North America in Documenta III, Kassel, Germany.

![[un]common threads](/www_michaelrosenfeldart_com/uncommon_threads_install_34.jpg)