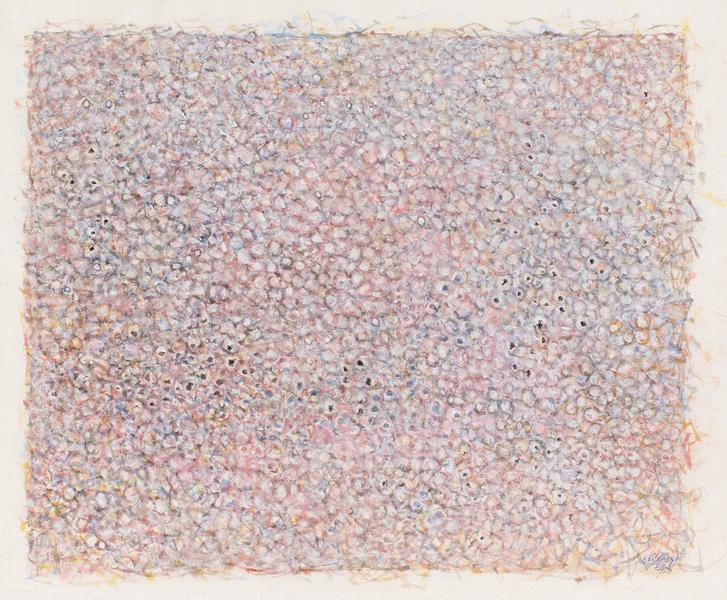

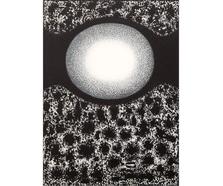

For me, the road has been a zig-zag into and out of old civilizations, seeking new horizons through meditation and contemplation. My sources of inspiration have gone from those of my native middle west to those of microscopic worlds. I have discovered many a universe on paving stones and tree barks. I know very little about what is generally called “abstract” painting. Pure abstraction would mean a type of painting completely unrelated to life, which is unacceptable to me. I have sought to make my painting “whole” but to attain this I have used a whirling mass. I take up no definite position. Maybe this explains someone’s remark while looking at one of my paintings: “Where is the center?”[1]

Best known for a visual language inspired by Japanese and Chinese calligraphy, Mark Tobey was born in 1890 in Centerville, Wisconsin. In 1909, his family moved to Chicago, and in 1911, Tobey left for New York to become a fashion illustrator. He soon returned to Chicago, and in 1913, he studied at the Art Institute. Back in New York a while later, Tobey had his first solo exhibition at Knoedler & Co. Gallery in 1917. In 1918, he converted to the Baha’i faith. Its teachings, emphasizing the oneness of all religions, all people, and all aspects of the world, had a profound effect on his work. In 1923, Tobey took a job teaching art at the Cornish School and moved to Seattle, where he met and befriended Teng Kuei, a Chinese student at the University of Washington. Through him, Tobey learned about Chinese calligraphic and painting techniques, and his interest developed into an artistic passion. Tobey spent the second half of the 1920s traveling in Europe and the Middle East; he returned in 1929, just in time to be included in Alfred Barr’s Painting and Sculpture by Living Americans exhibition at MoMA.

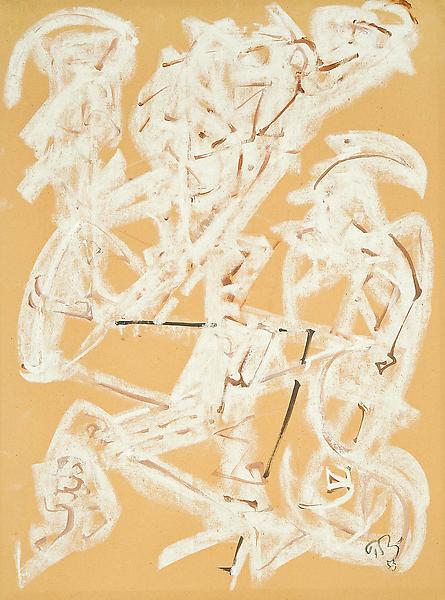

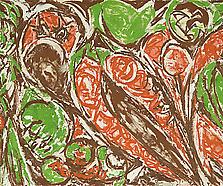

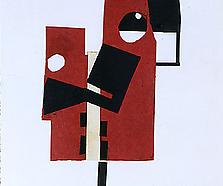

In the 1930s, Tobey again left the United States, taking a resident artist position at Darrington Hall in Devonshire, England from 1931 to 1938. During these years, he also traveled extensively in Asia and the Middle East, visiting Colombo, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Palestine, and Japan. The art he saw in China had a particularly strong influence on Tobey, affecting how he understood the world he saw around him, “When I looked at a tree,” he once explained, “it became a flame of rhythmic lines bursting out of the ground.”[2] He returned to New York in 1938 for what was supposed to be a brief stay, but the impending war in Europe prevented him from leaving the country. After settling back in Seattle, Tobey spent the next several years refining the “white writing” style he had devised while in Devonshire. He also developed his key concepts of “multiple space” and “moving focus.” In order to destroy the “hole in the wall” effect of Renaissance perspective (a description offered by Teng Kuei), Tobey conceived of the canvas as a series of spaces, each of which had its own focal point. Together, these multiple spaces formed a compound composition, one unified by calligraphic forms scattered across the canvas. Tobey was thus able to avoid the potential monotony of all-over compositions while also presenting an analysis of space that offered a radical departure from even the shifting planes of cubism and expressionism.[3]