“We are living in the midst of the most appalling and impossible not to be seen horrors and madness—everyone covers them with pretty rugs and wallpaper and chintz.”[1]

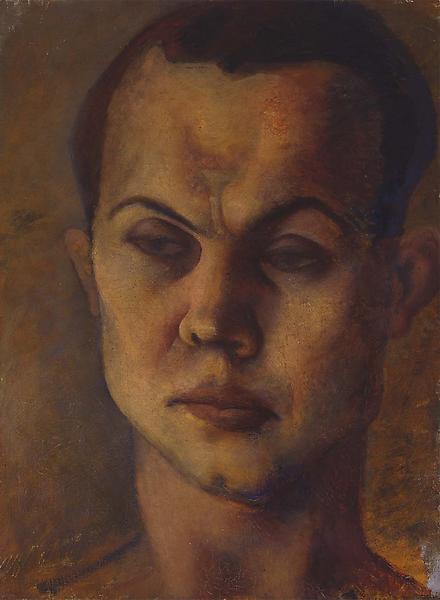

Born in 1898 to an aristocratic family, Pavel Tchelitchew was raised in Moscow until the Russian Revolution forced his family to flee. From 1918 to 1920, he studied at the Kiev Academy under Alexandra Exeter (a former pupil of Fernand Léger’s). In 1920, Tchelitchew moved to Odessa, where he worked on stage sets for local theaters, and in 1921, he moved to Germany. Settling in Berlin, Tchelitchew continued designing for theater productions including Le coq d’or at the Berlin Staatsoper.

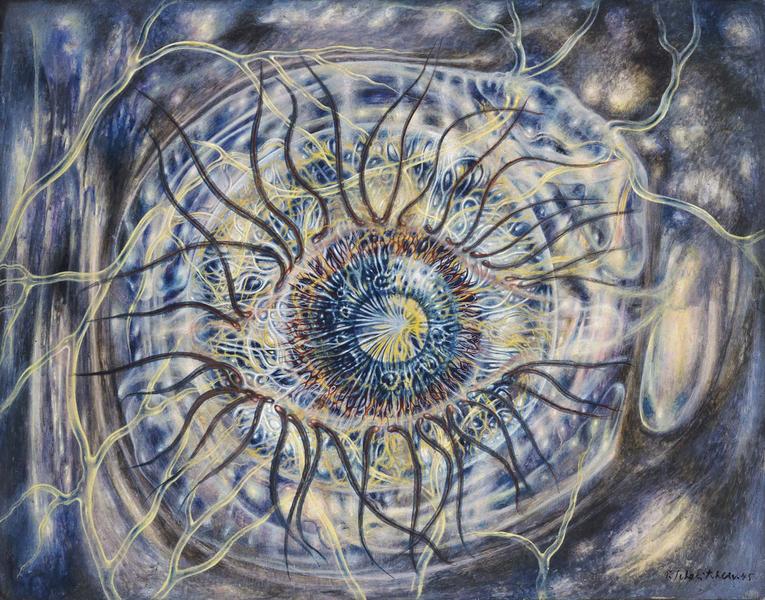

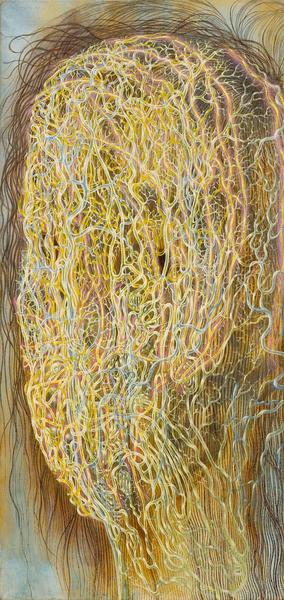

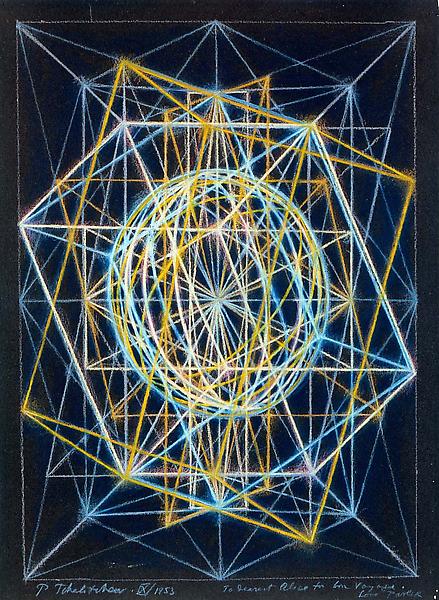

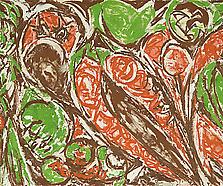

In 1923, Tchelitchew moved to Paris where he turned away from the influence of futurism and constructivism toward “a more realistic representation of objects treated as symbols of cosmic order: eggs, cabbages and constellations of stars.”[2] As Stephen Prokopoff explains, in Paris, Tchelitchew “became the ideologue of a small band of artists, known in France by the term Néo-Humanisme, who specialized in dream-like landscapes and figures in sombre, usually blue, tonalities; they included Eugene Berman and his brother Leonid Berman . . . Christian Bérard and André Lanskoy. Such work was … greatly indebted to Russian Symbolist painting at the turn of the century and enriched by Tchelitchew’s very personal elaboration of the simultaneous perspectives of Cubism.”[3] In 1925 when he exhibited an oil painting at the Salon d’Automne titled Basket of Strawberries, which aroused the interest of Gertrude Stein, and he soon became her protégé. More importantly, his use of the basket in this composition marked the beginning of his interest in visual analysis of the underlying structures within a variety of forms.

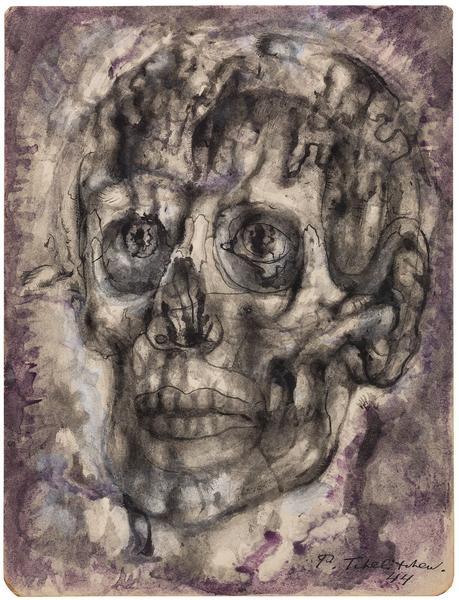

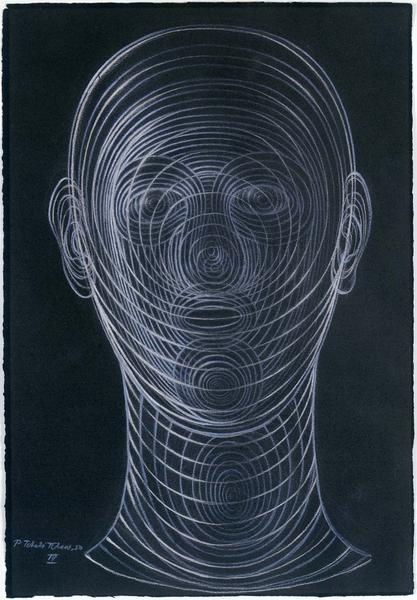

In the mid-1920s, Tchelitchew limited his palette to earth tones and continually pared it down until it consisted only of grays and whites. He used heavy impasto and sometimes incorporated coffee grounds and house paint. In 1926, he participated in a group exhibition at the Galerie Drouet with Bérard, the Berman brothers, and Kristians Tonny. Their shared emphasis on the human figure and its placement in romantic and melancholy environments led to their being collectively labeled neo-romantic. As he began creating metamorphic compositions—in which a particular image would be created out of thematically relevant forms (for example: clowns whose faces and bodies are comprised of circus figures)—Tchelitchew’s art became more closely associated with surrealism. However, while it shares surrealism’s unsettling quality reminiscent of a churning unconscious mind, Tchelitchew eschewed automatism as a technique. Instead, like the post-surrealists of the American West Coast, Tchelitchew chose his subject matter and composed his images with conscious deliberation.