“[With the Toilet of 1963] I had finally made Bob Arneson. I had finally arrived at a piece of work that stood firmly on its ground. It was vulgar, I was vulgar, I was not sophisticated, I was a vulgar person. And if you’re not sophisticated, you’re vulgar. You better be very real about that. But it was also, more significantly, a very important piece . . . the ultimate ceramic, and that was all about our Western civilization. It was also about all the symbolism and verbiage that one would put into what later became Pop Art at the same time, notions and sub-notions, subconscious and conscious, about our heritage.”[i]

Best known for expressionistic and irreverent ceramic self-portraits that doubled as commentary on humanity’s shortcomings, Robert Arneson was born in 1930 in Benicia, California, to parents who encouraged his interest in art. From an early age, Arneson demonstrated considerable talent, and as a teenager, Arneson was hired to draw cartoons for the Benicia Herald. In 1949, he enrolled in courses at Marin Junior College, where he continued to draw cartoons and comic strips. Encouraged by his professors, Arneson won a scholarship in his junior year to attend the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, and he received his bachelor’s degree in 1954. After college, Arneson stayed in the San Francisco Bay area and took a job teaching ceramics at Menlo-Atherton High School, in part because he could not envision a career as a ceramics artist and wanted to maintain a connection to his passion for the medium. In the summer of 1955, Arneson and his wife of six months traveled to Mexico where he saw and was inspired by the various works of pottery and ceramics, both traditional and modern. Upon his return to California, Arneson sought out various forms of artistic nourishment, frequenting museums and bookstores, including City Lights, a center for Beat culture at the time. In 1956, he decided to quit his teaching job and pursue his MFA at Mills College, graduating in 1958. He returned to teaching, first at Santa Rosa Junior College, and then at Freemont High School in Oakland, where he started a ceramics after-school program. In 1962, Arneson began a long and distinguished teaching career at the University of California Davis, a position he held until a year before his death from liver cancer at age sixty-two.[ii]

While in graduate school, Arneson became more confident in his belief that fired clay could stand alongside marble and bronze as a legitimate artistic medium. This conviction was affirmed in 1957, when he saw an abstract clay pot by Peter Voulkos at the state fair. Appropriately, it would be at another state fair, in 1961, when Arneson transformed the nature of ceramics from the decorative and the function into the sculptural: “The liberating act was the closing of a thrown clay form in the shape of a soda bottle with a cap on which he marked No Return, and indeed, it was a point of no return. This iconoclastic gesture destroyed the vessel as a container, and conceptually transformed the object as subject.”[iii] The piece, No Deposit, No Return (1961) was an expression of Arneson’s keen interest in challenging the rigid boundary that western art critics had long ago erected between “artist” and “craftsman,” and that many artists themselves continued to support. This concern helped to distinguish Arneson’s sculptures of objects from the pop art works with which it is sometimes confused. Another important distinction emerges from the reasons behind Arneson’s preference for clay as a medium. It was, he once stated, “that one material that’s going to leave the imprint of your hand.”[iv]

In 1960, Arneson had his first exhibition: a two-man show with Tony DeLap at the Oakland Art Museum. Two years later, his work was included in a crafts exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. In 1963, Arneson was invited to participate in California Sculpture, an exhibition of 100 California artists on the roof garden of the Kaiser Center. Daunted by the prospect of representing himself in an exhibition that would include artists he greatly admired, Arneson produced a toilet. Although the work was ultimately pulled from the show, it became the first of several brightly colored ceramic toilets he created. “With Toilet . . . Arneson aimed a biting satire at the abstract expressionist aspiration of letting everything within the artist spill out freely in the work. The heavy, monochromatic stoneware of Toilet resembled the ceramic sculpture of Voulkos. In addition, Arneson treated the surface with an abstract expressionist touch. Despite his satirical irreverence, Arneson's outrageousness stems from and even pays homage to the iconoclasm of abstract expressionism itself.”[v] In 1967, he joined Wanda Hansen’s gallery, and that same year, his work was included in Funk, an exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum of the University of California, dedicated to the funk art of the San Francisco Bay area. This exhibition brought national recognition to Arneson, and soon after, Arneson took a sabbatical from Davis and rented a studio space in New York.

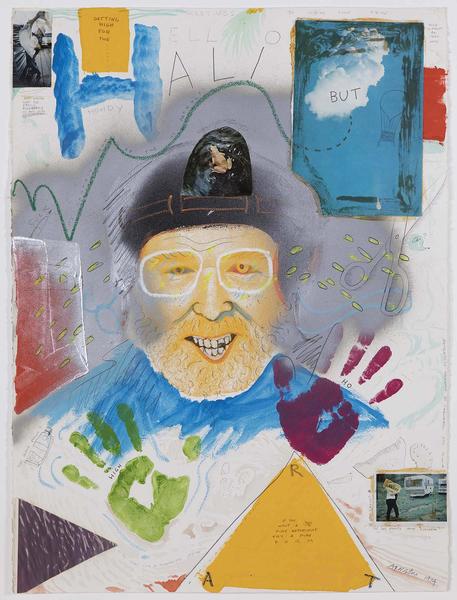

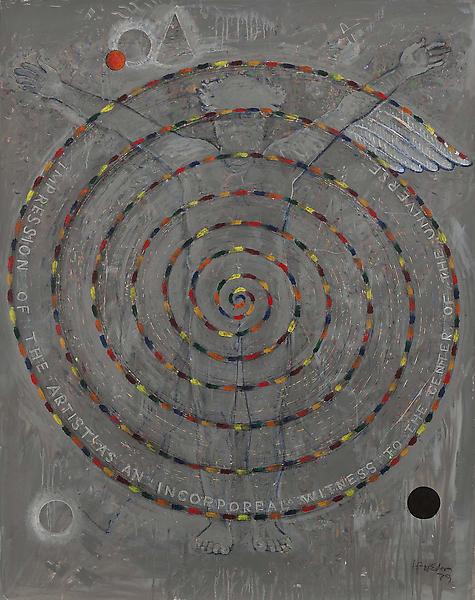

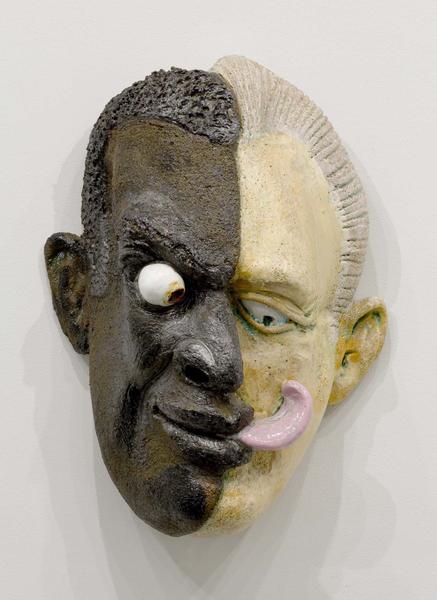

In the 1970s, Arneson turned to self-portraiture as a way to interrogate the direction American culture seemed to be taking in the wake of the Vietnam War. Scholar Jonathan Fineberg notes that in “the post-Vietnam era, a climate of ethical relativism and complexity emerged, along with an increasingly social construction of the self. We had begun to define ourselves by our possessions and by the perceptions of others to a degree that was fundamentally new and in a way that reflected or perhaps derived from profound changes in the ways in which people in the late twentieth century had begun to see the world.”[vi] This critique was not always well-received, and Arneson noticed that viewers often responded to the humor in his work not just negatively, but as if he had offended them personally.[vii] Although Arneson puzzled over the reaction of personal offense, it makes sense given the cultural landscape painted by Fineberg. In the context of the increasing obsession with the self that characterized the “me generation” of the 1970s (and that has not yet abated), all offense is personal.

In 1974, Arneson met Allan Stone, who became his New York art dealer. That same year, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the San Francisco Museum of Art mounted a mid-career retrospective of his work. Arneson’s career steadily rose throughout the 1970s, sometimes with mixed reception from the public. In 1981, the Moscone Convention Center rejected a bust of George Moscone, the San Francisco mayor who, with Harvey Milk, was assassinated by Dan White in 1978. The bust was to be the centerpiece of the convention center, but Arneson’s choice to include certain elements, such as a Twinkie (signifying White’s infamous “Twinkie defense”), was deemed inappropriate. Despite the controversy, Arneson continued to use ordinary objects as a way of creating tension between the mundane and the traumatic. As curator and art historian Leo Mazow points out, “Arneson exploited the incisive and provocative potential of ubiquitous and seemingly innocuous articles from everyday life.”[viii]

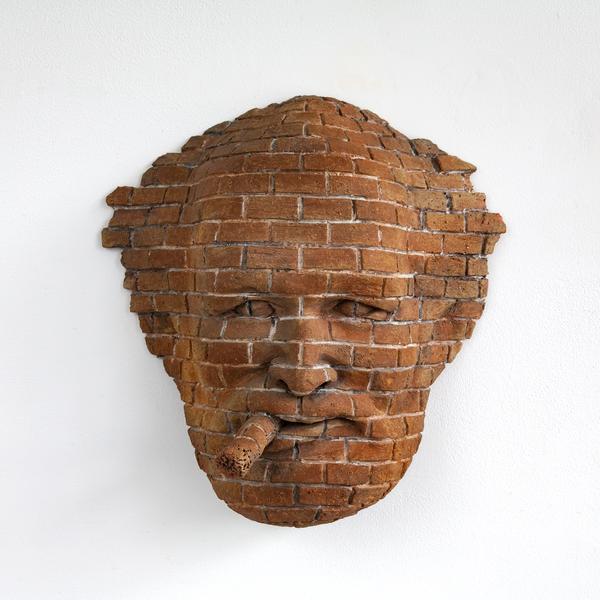

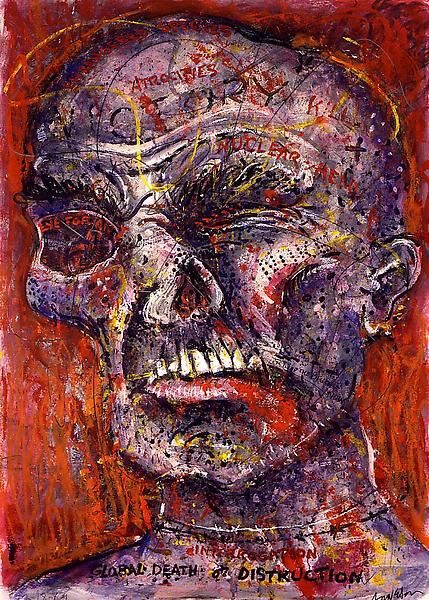

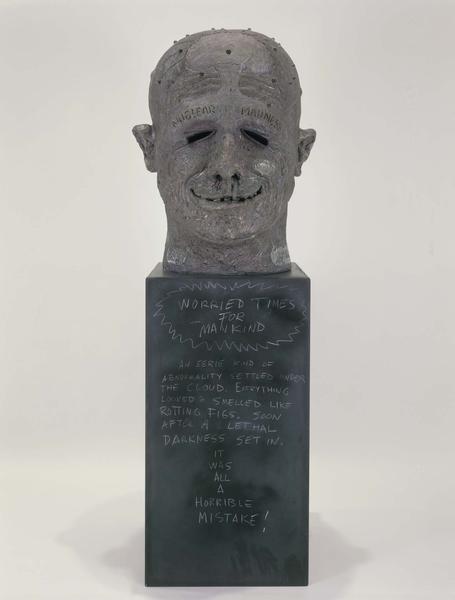

In the 1980s, these objects became less innocent as Arneson began using his art to protest against nuclear arms and the expansion of US militarism around the world. These works were often devastating not only in subject matter, but also in their combination of brutality of form and beauty of execution. From 1982 to 1983, he worked on a sculpture called Holy War Head, in which a childish, beaten head rests on top of a pedestal. To achieve the effect of a damaged human skull, Arneson beat the head with a baseball bat before the clay was fired. On the pedestal, he inscribed text taken from John Hershey’s 1946 report on the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima and the aftermath of nuclear destruction. The inscription describes the devastating effects of radiation. The following year, Arneson’s preference for satire mixed with tragedy resulted in General Nuke, a head of a snarling US general, whose nose has grown into a nuclear missile. Another “war head,” this time with vivid red blood running down the side of his mouth, the general sits on top of a black cylinder comprised of tiny corpses piled on top of one another.

Arneson’s critiques of American society stemmed from compassion rather than misanthropy. His provocative and often scathing studies of humanity were always tempered with a deep affection for people. His juxtaposition of opposing elements and sentiments—the comically grotesque with highbrow culture, anger with affection—earned him national acclaim and helped to establish San Francisco as a vital center for artistic creativity.

Arneson exhibited regularly in group shows and solo exhibitions throughout his career. He has also been the subject of numerous posthumous retrospectives, and solo and group shows. His work is represented in public collections throughout the world, including: the Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum (Seto, Japan); Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC); Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles, CA); The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY); Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY); National Gallery of Australia (Canberra, Australia); Oakland Museum of California (Oakland, CA); Orange County Museum of Art (Newport Beach, CA); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, CA); Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park (Kōka, Japan); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York, NY); Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam, The Netherlands); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art (Hartford, CT); and Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY).

[ii] Jonathan Fineberg, A Troublesome Subject: The Art of Robert Arneson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

[iii] Leopold Foulem, “Arneson and the Object,” Ceramics: Art and Perception no. 61, (2005), 21.

[iv] Arneson, in California Clay in the Rockies, documentary film by Chris Felver, n.d.

[v] Fineberg, Art since 1940: Strategies of Being (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1995), 286.

[vi] Fineberg, A Troublesome Subject: The Art of Robert Arneson, 6.

[vii] Arneson, in California Clay in the Rockies.

[viii] Leo Mazow, “Arneson and the Object,” Arneson and the Object (University Park, PA: Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University, 2004).