To download the online exhibition catalogue, click here.

“I felt that if the themes in my early paintings, those very specific psychological concerns, were as significant as I thought they were, then I had a rationale for figurative painting. That was a time when a figure painter needed a justification for not doing Abstract Expressionism... Abstraction symbolized immediate experience for the Abstract Expressionists. It did just the opposite for me. Since I was so obsessed with myself, so troubled by my relation to the world that seemed vague or even chaotic, it was natural that so-called figurative style – a style that could give me an image of myself – would seem more immediate. An abstract style suggested a world more distant, a world I wanted to reach. . . Say you draw a picture of your own face. It takes an enormous amount of abstract thinking to get your hand to do what you want it to do. And the result is a visual abstraction made from the tangible reality of your face. So there is a great deal of abstraction involved in that self-image. It’s the same with any image an artist makes. They are all abstraction from the self. They all reflect that artist’s sense of self. All art is figurative, in a certain way. . . But every figure of the self is a disguise. Everything humans make is an attempt to make a mirror. The face in a painting is a mask. It covers a reality that is ultimately ungraspable. . . Despite this ideal of complete integrity, of art absolutely at one with itself, my earliest paintings show that I was satisfied only when I could see a kaleidoscope of possibilities. That’s why I could never keep abstraction out of my figurative work.”

—Pat Steir, quoted in Carter Ratcliff, Pat Steir Paintings (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1986), 10.

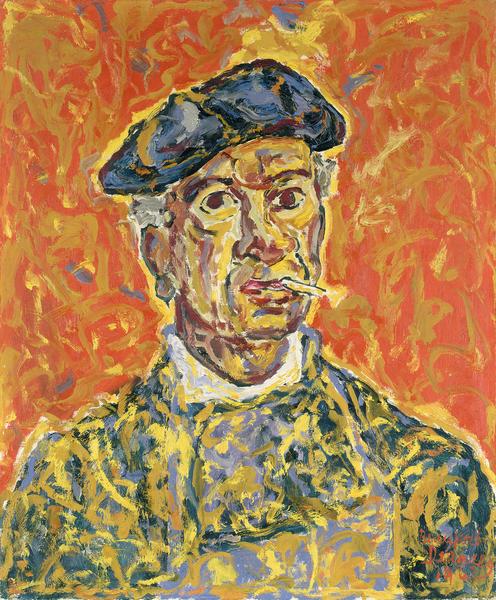

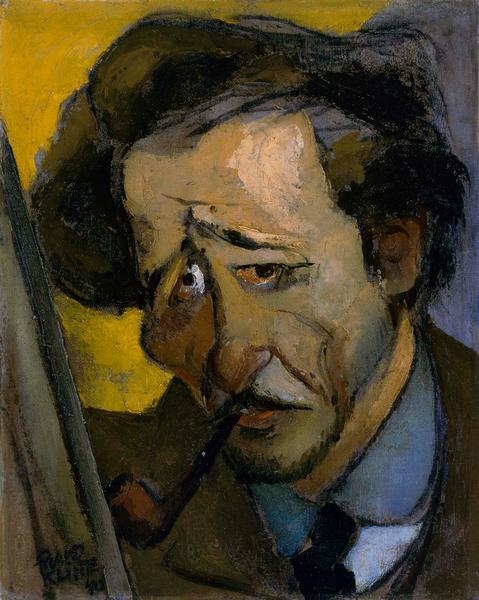

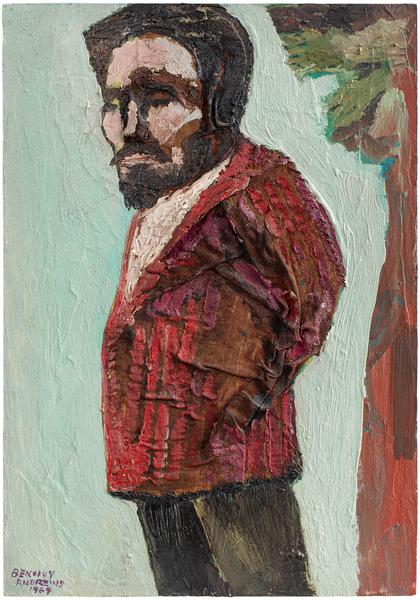

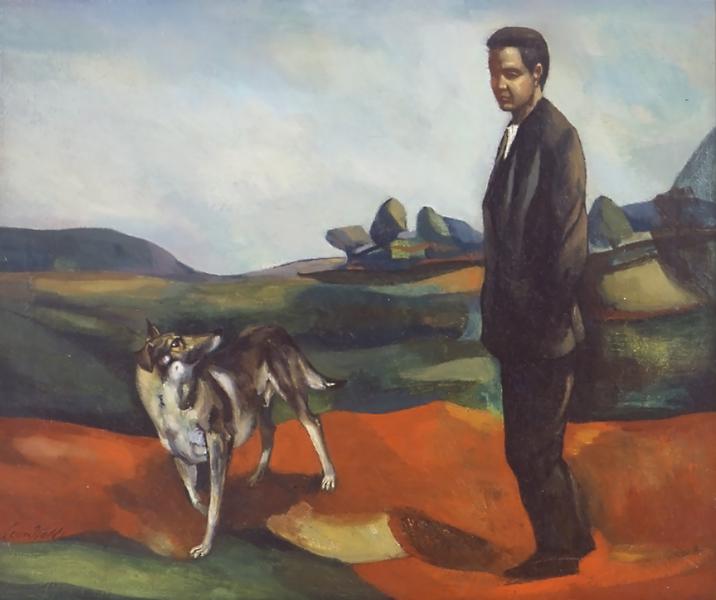

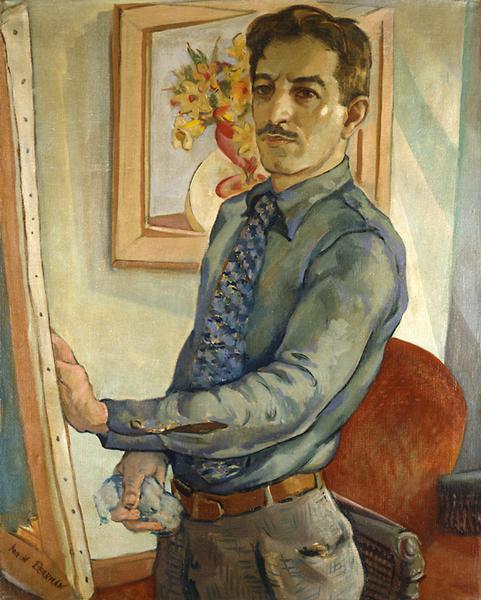

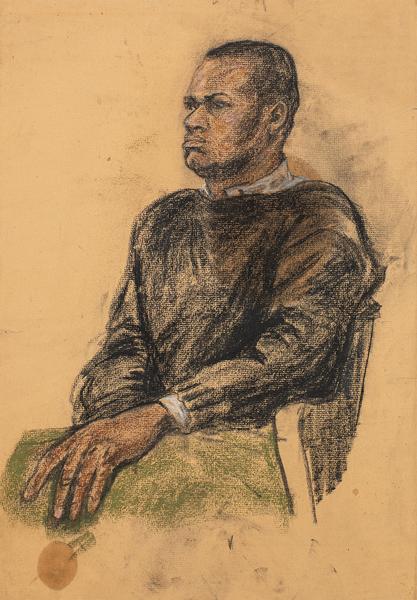

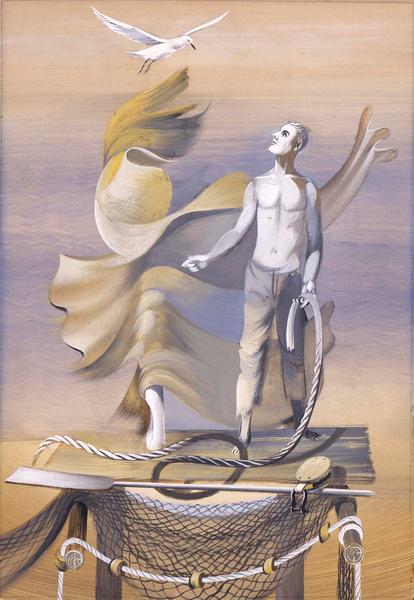

The artist – as sole creator – determines how they will be seen, viewed and remembered through self-portraiture. Consciously or not, as Alfonso Ossorio declared, “Every artist projects a philosophy in everything he does.” [1] By carving out their own sense of identity with a language and style uniquely their own, they determine what that framework will be and how it will be used to communicate how they want to be seen, viewed and remembered. Whether through abstraction – using light, color, texture and emphatic brushwork – or employing a more figurative, representational mode – self-portrayal is a unique and singular expression that tells a complete story of the artist and their intentions.

Fully in control, artists also determine the lens through which they will be seen – whether with critical introspection, wit and humor or cool detachment. Artists choose their style, palette, setting, emotional state, pose and accoutrements to symbolic effect – ones that describe, enhance or aggrandize their sense of self for themselves and for the world at large. The artist chooses what to reveal and what to leave, instead, to the imagination. They include objects or companions in order to express what is important to them as a record of time. Sometimes the moment represents a very finite time in a very specific place and thus, we could watch the artist grow if we wanted to, observing the toll of age over the years as life continued onward. Other times, this moment of being is one that is projected or imagined, one that transcends time and place – a version of the artist in a space that is not so readily recognizable and familiar.

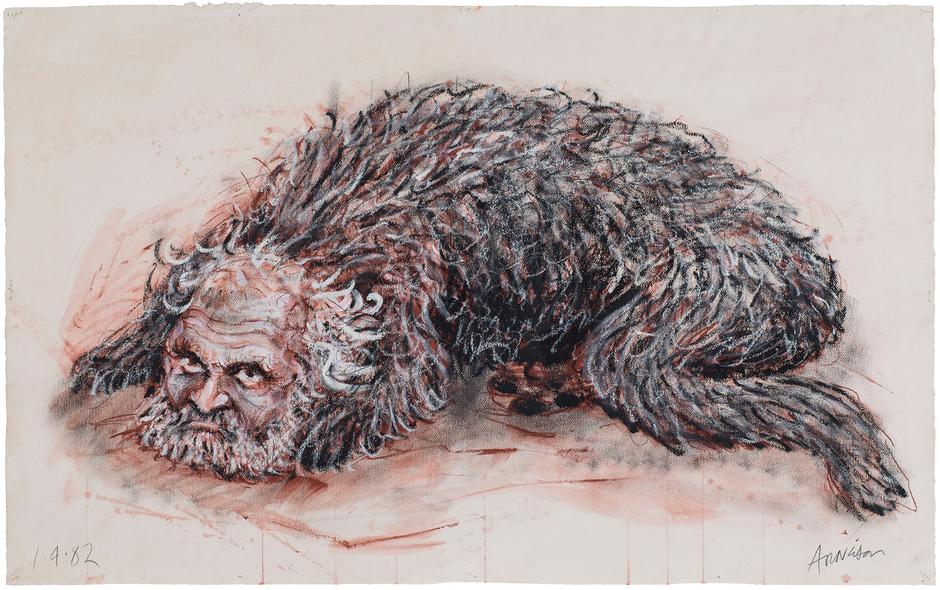

By conveying their own vision of themselves, artists affirm their sense of personhood as well as artisthood. The artist juggles a dual identity – of both person and artist – while also shaping how they are being viewed and remembered as they cement their legacy for themselves and others. Together with, and in addition to, this duality, artists also use self-portraiture as a vehicle for self-exploration as a way to simultaneously distance or bridge self from “other” – real from artificial – thereby further compounding the notion of identity. In so doing, they adapt and employ their form to take on different roles, like an actor. Robert Arneson, known for his many daring experiments in self-portraiture, explained: “You’re modeling in the most traditional manner. So you use yourself, but this self is not the inner self. You end up acting, becoming someone else although you use your own features.”[2] Like Pat Steir, he noted, “I never did a self-portrait. I always use a self-portrait as a mask.”[3]

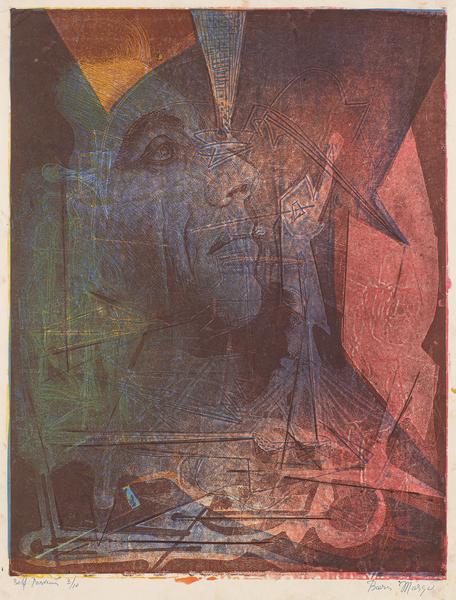

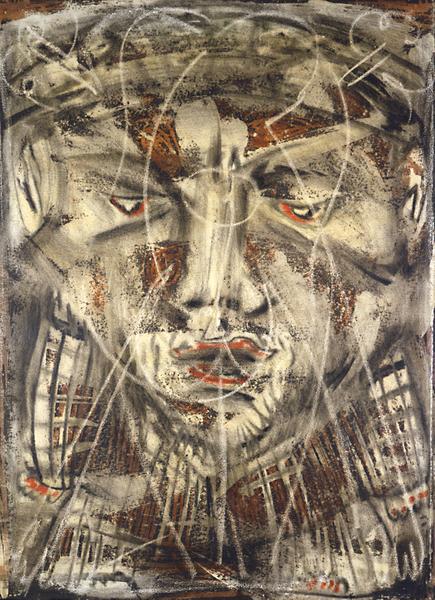

Self-portraiture has evolved throughout art history thanks to the advent of photography and technological advancements. There are more ways of seeing, reflecting and projecting back to ourselves and the viewer than just the mirror. Through cellular phones and the ubiquitous proliferation of selfies, the camera has dramatically influenced where, when and how we depict ourselves. During times of critical introspection – as an individual and as a collective whole – we all want to be seen and heard. In contemplative, poignant and penetrating self- portraits Benny Andrews, Robert Arneson, Aaron Berkman, Willem de Kooning, Beauford Delaney, Nancy Grossman, Leon Kelly, Franz Kline, Boris Margo, Alfonso Ossorio, Theodore Roszak, Raphael Soyer, Pat Steir, Louis Stone and Bob Thompson immortalize themselves. Their depictions remind us to look at ourselves, to recognize who we are, and to give us direction when the path ahead doesn’t always seem clear. Now, more than ever, our voice and our vision matters.

[1] Alfonso Ossorio, in Forrest Selvig, “Oral history interview with Alfonso Ossorio,” November 19, 1968, transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/ oralhistories/transcripts/ossori68.htm.

[2] Robert Arneson, quoted in Jonathan Fineberg, A Troublesome Subject: The Art of Robert Arneson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 13.

[3] Arneson, quoted in Fineberg, 98.