For almost sixty years, Charles Seliger (American, b.1926) has passionately pursued an inner-world of organic abstraction, celebrating the structural complexities of natural forms. Like many artists of his generation, Seliger was deeply influenced by the Surrealists’ use of automatism, and throughout his career he has cultivated a deeply poetic style of abstraction that explores the relationship of order and chaos found in nature. Attracted to the inner structures of plants, insects and other natural objects, and inspired by a wide range of reading in natural history, biology and physics, Seliger’s abstractions pay homage to nature’s infinite variety. His paintings have been described as ‘microscopic views of the natural world,’ and although the references to nature and science are appropriate, his abstractions do not directly imitate nature so much as suggest its intrinsic structures.

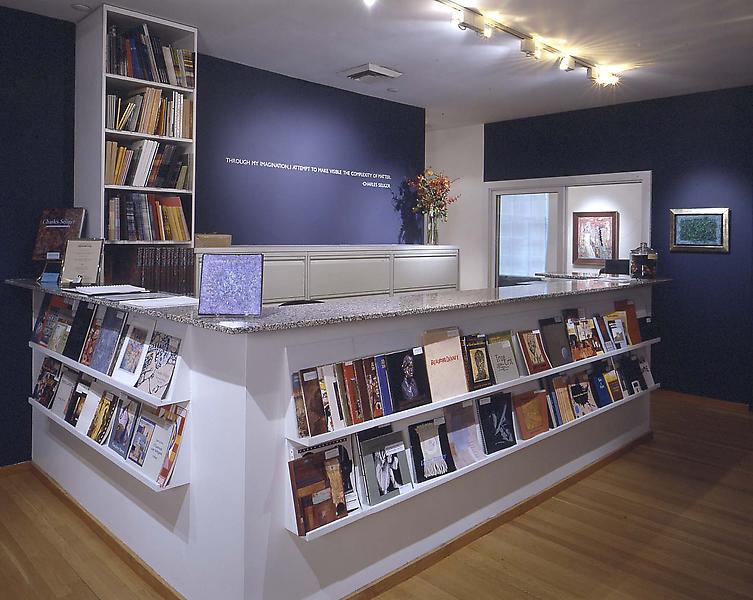

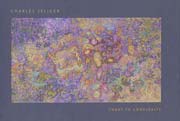

Chaos to Complexity is Michael Rosenfeld Gallery's seventh solo exhibition of Seliger's work and features thirty paintings completed from 1999 to the present. This exhibition coincides with the release of the monograph Charles Seliger: Redefining Abstract Expressionism, by Francis V. O'Connor, published by Hudson Hills Press. (Hudson Hills Press).

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC is the exclusive representative of Charles Seliger.

The following is John Yau's essay from the Chaos to Complexity exhibition catalogue:

Charles Seliger and His Syncretic Abstraction, by John Yau

Among the most widely held views of Abstract Expressionism is the notion that it can be divided into two tendencies, the gestural and the geometric. A number of conclusions have been drawn with this viewpoint in mind, a key one being that in his poured paintings, Jackson Pollock was able to go beyond gesture, thus bringing about its demise. One effect of this notion is that the kind of expressionist brushwork we associate with someone like Willem de Kooning has never again been held in high regard. Another conclusion is that, in the decade following Pollock’s death in 1956, the geometric ascended while the gestural devolved. Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt paved the way for Frank Stella and Minimalism, while, at best, de Kooning led to “second generation Abstract Expressionists” such as Norman Bluhm and Joan Mitchell. Among the numerous subtexts lurking within this narrow narrative is the assumption that Stella was able to create wholly American (and therefore truly new) art, while Bluhm and Mitchell were unable to sever their ties to European-inspired gestural painting, particularly as exemplified by de Kooning. Like a fairy tale with a predictable, happy ending, this view makes history and its subsequent unfolding neat and orderly, but it hardly addresses the real and far more complex story. A crucial component of that other history is the work of Charles Seliger, a truly unique American phenomenon.

In order to begin to recognize the importance of Seliger’s achievements and their relevance to current modes of abstraction, it is necessary to mention a few salient details of his life. He was born in New York in 1926, and thus chronologically belongs to the same generation as Michael Goldberg (born 1926) and Helen Frankenthaler (born 1928). However, what isolates him from his own generation and connects him instead to the Abstract Expressionists (who are at least a decade older) is that Seliger exhibited his work in 1943 at the Norlyst Gallery; since then, he has continued to exhibit regularly in the United States and Europe. In 1943, he began experimenting with automatism, and it has remained an integral part of his process. In 1945, he had his first solo show at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery. In 1947, when Guggenheim closed her gallery and moved to Venice, Italy, she donated three paintings - two by Seliger and one by Jackson Pollock - to the permanent collection of the University of Iowa.

During these years, the precocious, self-taught teenager met many prominent and emerging figures, including André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Max and Jimmy Ernst, Adolph Gottlieb, Gerome Kamrowski, Robert Motherwell, and Pollock. Seliger’s friends and acquaintances constitute a who’s who of the international art world. In hindsight, it seems remarkable that Seliger was never overwhelmed by the circle of brilliant older artists to which he belonged. Despite the heady artistic and literary milieu in which he moved, he was able to establish and pursue his own direction, which he continued to do for over six decades.

Seliger was able to maintain his own vision in the midst of those around him because he is a classic autodidact. Like two other notable autodidacts, Jasper Johns and Robert Ryman, Seliger did what most artists find impossible - he invented his own occasion. Johns has said he wanted to discover “what was helpless in my behavior.” Ryman’s education, which took place in the Museum of Modern Art (New York), where he worked for seven years, was propelled by his desire to “find out how things worked.” In 1940, at the age of fourteen, Seliger began frequenting New York galleries and museums; it is during this time that he began to visit Julien Levy Gallery, Pierre Matisse Gallery and other galleries that showed work by the Surrealists. In 1945, when he was nineteen, he stated: “I want to apostrophize micro-reality. I want to tear the skin from life, and, peering closely, paint what I see. I want my brain to become a magnifying glass for the infinite minutiae forming reality. Growth is the poetry of all art.” As their statements make clear, each of these artists found his own way into art, as well as developed his own permissions.

Consistently a devoted student, Seliger possesses a singular inquisitiveness, a bottomless patience, and a need to be absolutely precise, character traits that observers have long recognized as being central to both Johns and Ryman. The connection between them goes deeper than their autodidacticism. For one thing, like Johns and Ryman, Seliger is neither an eccentric figure nor someone who has managed to carve a unique, but somewhat isolated niche for himself. In fact, the opposite is true. He is an important part of the mix, and his work embodies a centrality that has yet to be fully acknowledged.

In recent years, Seliger’s centrality has become more obvious; he has presaged a number of routes currently being explored by both younger and established artists. His syncretic painting expands our understanding of modernism’s capabilities. By drawing on a wide array of disparate sources, ranging from botany and physics to Mughal miniatures and Islamic calligraphy, he offers a useful alternative to modernism’s reductive tendencies. Instead of regarding his work as an anomaly, an incredibly beautiful cul-de-sac in the history of painting, we should recognize to what extent Seliger has contributed to a vibrantly fertile current of artistic possibility running from recent history (modernism) to the unfolding present (postmodernism) and, we may imagine, well beyond.

There are many reasons for Seliger’s marginalization within the standard history of Abstract Expressionism, the most obvious being scale. When we think of Abstract Expressionism, we think of large-scaled paintings, or what Clement Greenberg termed the “polyphonic” picture, which he believed provoked “the crisis of the easel picture.” From the beginning of his career, Seliger has preferred to work on a small scale. His paintings from the 1940s are small, even by Surrealist standards, and often measure less than twenty-four inches by eighteen inches. His paintings since the early 1950s, when he came into his own, are neither easel pictures nor miniatures. Rather, they are something altogether unique: a highly detailed vision of both the infinite and the subatomic. However, because we so often understand gesture as writ large, we fail to recognize that within the small format he has chosen, Seliger also explores gesture. After all, isn’t gesture a combination of matter and energy? Seliger is not interested in gestural action, but in the unseen phenomenon that constitute nature’s gestures, from the Big Bang to the botanical. He comes to gesture from a different perspective, as a visionary observer rather than as a heroic practitioner.

In the current exhibition, Chaos to Complexity, the largest painting measures ten by eighteen inches, and the smallest one seven by five inches. While it is understandable to see Seliger’s scale as proof of his modesty, it is a mistake to do so. It is also a mistake to believe that his preference for working on a small scale makes him derivative of Paul Klee, an acknowledged master of the diminutive. For one thing, Klee was not interested in either spatiality or the unity of the picture plane, which is to say he had only a passing interest in pure abstraction. Because Seliger’s lines and dots are essentially abstract, and never function in a didactic way, his linearity differs significantly from Klee’s. In Seliger’s best paintings, the delicate tracery and meandering dots hover between description and pure color, which Klee’s work simply does not do. In many of the paintings, the dots and tracery seem poised and ready to detach themselves from the material world.

In their myriad details, opulent opticality, translucency, layering, delicacy and compression, Seliger’s paintings are unrivaled, and the artist’s dazzling embrace of color only further elevates these paintings into a realm all their own. To begin to appreciate Seliger’s mastery of color, imagine trying to tally and name each color, tone and hue inhabiting even a handful of his paintings.