Benefit Preview: Tuesday, October 29

Wednesday, October 30, 12–7PM

Thursday, October 31, 12–7PM

Friday, November 1, 12–7PM

Saturday, November 2, 12–6PM

Visit Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in Booth D16

“Actually, I've only painted one picture in my entire life … I see my totality of 300 years of history of black people through one little fraction … a family … my family. … I don't try to record it, but use it symbolically to make a very broad universal statement about the search for dignity, the search for a deeper understanding of the conflict and the contradictions of life … so that there is more to it than just the illustrative portrayal of a history of a family … what I'm trying to do is talk about the history of humanity.” [1]

—Charles White (1918–1979)

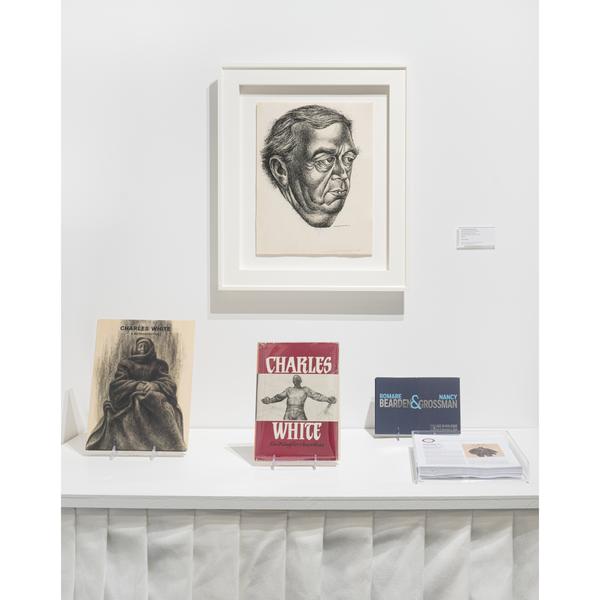

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is pleased to participate in The Art Show 2024 with Charles White, a solo exhibition of paintings and drawings from each period of the artist’s career with particular emphasis on the Civil Rights Movement era. Bringing together a compelling selection of major works dating from 1936 to 1975, Charles White offers a concise survey of the artist’s style as it evolved over four decades in his relentless endeavor to affectively convey the humanitarian themes that were the primary concern of his art.

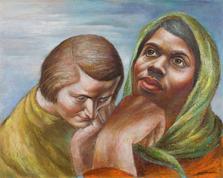

Active in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, Charles White produced a powerful body of figurative compositions depicting subjects drawn from the rich history of Black America and the world around him. His prolific oeuvre comprises social realist scenes, narrative compositions of historical subjects, and a large body of portraiture depicting political leaders, creative luminaries, and everyday Black Americans from all walks of life. White’s allegorical compositions of the 1960s are especially well-represented in Michael Rosenfeld Gallery’s presentation with a group of large-scale drawings that exhibit his masterful technical skill and directly address the social and political injustices endemic to Black American life. White’s art evolved through various styles over a forty-year period as he adapted his approach to adequately convey his shifting interests, but he never wavered in his dedication to portraying Black Americans in “images of dignity,” as he put it.

Highlights of Charles White include two major portraits of venerated musical artists, Paul Robeson (1973) and Leadbelly (1975). Commissioned by photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks (1912–2006) for the promotional art and soundtrack album cover associated with the 1976 film Leadbelly—which Parks directed—White’s portrait is an elevating portrayal of the blues legend, who he renders in titanic proportions reflective of the indelible impact he had on twentieth-century music. Paul Robeson is similarly monumental in scale but takes a tondo format, focusing the eye on the baritone’s exquisitely rendered face gazing heavenward at a dappled beam of light. Chosen by White for its ties to Renaissance portraiture, the tondo functions as “a framing device that subtly evokes a cosmic sense of the measureless or boundless.” [2]

White’s Mural Study for Camp Wo-Chi-Ca (1945) is a rare preparatory drawing for a mural at the Worker’s Children’s Camp in New Jersey, where he taught art and met his second wife, Frances Barrett. Reflecting his admiration for the Mexican muralists and incorporating iconography from the indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest, the traditional arts of Africa, and the spiritual practices of the Far East, the drawing synthesizes White’s diverse cultural interests while articulating his vision for an equitable standard of education that advances a cosmopolitan world view. Booth D16 also features prime examples of White’s beatific portrayals of Black women with Let the Light Enter (1961) and J’Accuse No.3 (1965). Dedicated to poet and abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911), Let the Light Enter is emblematic of White’s exalting portrayals of historical figures, which often strove to recuperate overlooked or underknown leaders from Black American history while drawing parallels with the contemporaneous struggle for civil rights. J’Accuse No.3 belongs to a series titled after nineteenth-century French writer Émile Zola’s famous indictment of the French state’s systemic discriminatory practices that resulted in the Dreyfus Affair. Portraying a woman’s serene, upturned face emerging from an ethereal, swirling atmosphere of light and dark, J’Accuse No.3 allegorizes the steadfast fortitude of innumerable anonymous civil rights activists who sought political justice from a prejudicial government.

A primary example from the Nobody Knows My Name series—titled after James Baldwin’s 1961 essay collection—rounds out the exhibition’s focus on the 1960s. Illuminated by a crack of light in an otherwise dark space, the subject of Nobody Knows My Name #1 (1965) is a young man who gazes into the space of the viewer with a calm seriousness. Poetically symbolizing the subject’s struggle for recognition from a society that seeks to ignore and suppress him, the drawing epitomizes what art historian David C. Driskell wrote of White’s series and Baldwin’s book: “With genuine concern for having one’s presence acknowledged, for being visible, comes recognition that communal interaction is one of the things that makes us human.” [3]

The resurgent interest in Charles White’s life and oeuvre in recent years is in large part due to the landmark touring exhibition co-organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and The Museum of Modern Art in New York, Charles White: A Retrospective (2018–19). Curated by Sarah Kelly Oehler, the Institute’s Field-McCormick Chair and Curator of American Art, and Esther Adler, MoMA’s Associate Curator of Drawings and Prints, the exhibition presented over one hundred works dating from 1935–79. Two major works on view in Michael Rosenfeld Gallery’s Art Show 2024 presentation were recently featured in the critically renowned historical survey Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (October 2023–April 2024), curated by Ashley James, the museum’s Associate Curator of Contemporary Art.

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has championed the work of Charles White for over thirty years. The artist was a fixture of the gallery’s acclaimed annual exhibition series African American Art: 20th Century Masterworks (1994–2003), and in 2009 the gallery mounted Charles White: Let the Light Enter, Major Drawings 1942–1970, the catalogue for which first published a 1960s radio interview with the artist released to the gallery by the Charles White Archives. In 2018, the gallery organized the widely praised exhibition Truth & Beauty: Charles White and His Circle, which surveyed the artist’s career while contextualizing his work within a larger milieu of figurative artists whose work addressed social and political subjects. The accompanying catalogue published texts discussing White’s art, career, and influence by Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, John Biggers, Eldzier Cortor, Ernest Crichlow, Jacob Lawrence, Hughie Lee-Smith, and Hale Woodruff.

1. Charles White quoted in Edmund W. Gordon, “First and foremost, an artist” in Freedomways: A Quarterly Review of the Freedom Movement vol. 20, no. 3, special issue “Charles White: Art and Soul” (1980): 137

2. John P. Murphy, “Vision, 1973,” in Veronica Roberts, ed., Charles White: The Gordon Gift to The University of Texas (Austin, TX: Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, 2019), 37.3.

3. David C. Driskell, "Foreword," in Andrea D. Barnwell, Charles White (Rohnert Park, CA: Pomegranate Communications, Inc., 2002), ix