“I am interested in the social, even the propaganda, angle in painting; but I feel that the job of everyone in a creative field is to picture the whole scene … I am interested in creating a style that is much more powerful, that will take in the technical end and at the same time will say what I have to say. Paint is the only weapon I have with which to fight what I resent. If I could write, I would write about it. If I could talk, I would talk about it. Since I paint, I must paint about it.”[1]

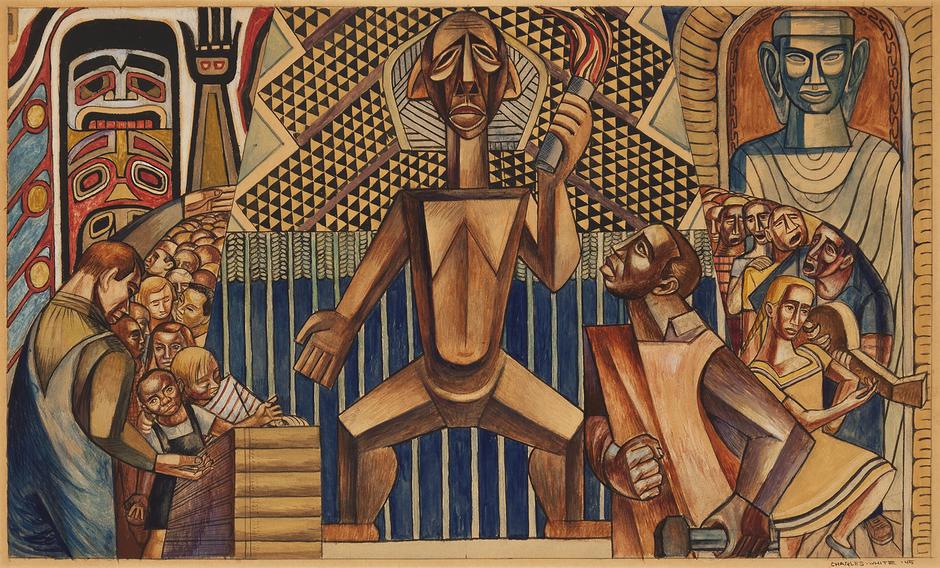

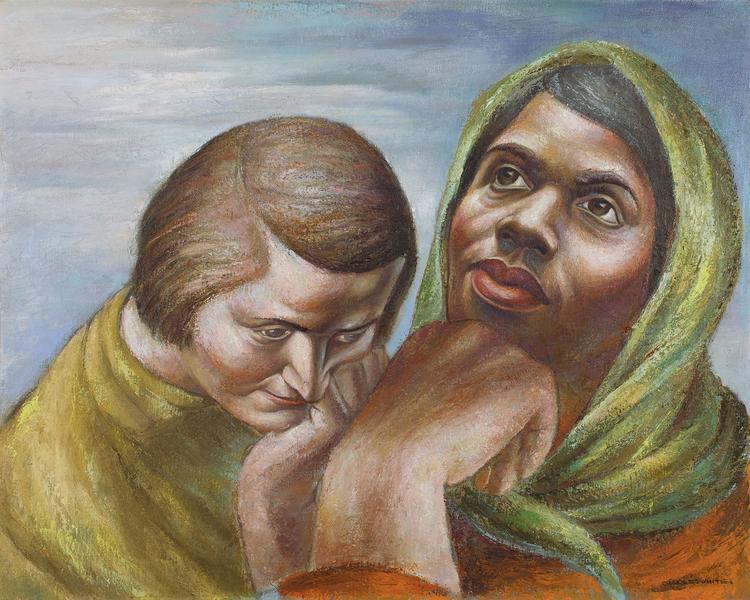

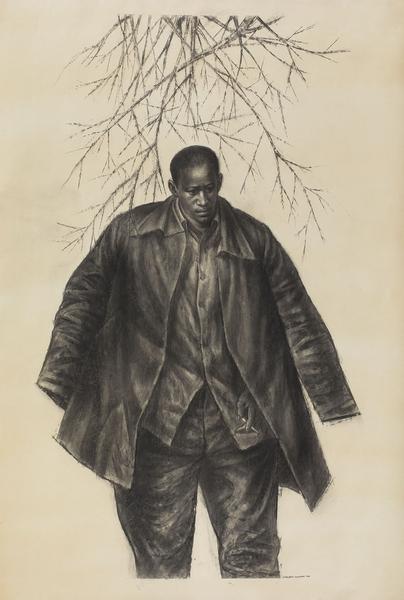

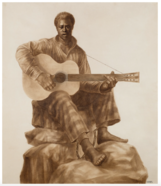

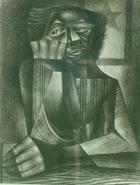

Charles White is one of the great interpreters of the human experience who, over the course of a five-decade career, executed an unparalleled body of paintings, drawings, prints, and murals depicting Black American life, history, and culture. White is celebrated for his portraits of historical figures, creative luminaries, and political leaders including John Brown, Harry Belafonte, Paul Robeson, Bessie Smith, Harriet Tubman, and Nat Turner, as well as everyday African Americans from all walks of life such as field laborers, factory workers, soldiers, preachers, musicians, children, and women. The strength and fortitude of the human spirit captured in his images counteract racist stereotypes and advocate for action against inequality. From his early experiments with modernism to his late allegories of struggle and triumph, White never wavered in his dedication to portraying Black Americans in “images of dignity,” as he put it.

Charles Wilbert White was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1918.[2] His mother, Ethelene Gary, was a domestic worker who had moved to the city from Mississippi four years earlier. Charles spent many formative hours of his childhood at the local public library after one of the librarians agreed to look after him while Ethelene was at work. This experience exposed Charles to art and literature and instilled in him a love of reading that his mother further encouraged. She bought him his first set of oils when he was seven, and he learned how to mix paint by watching a group of art students at a park adjacent to the Art Institute of Chicago. Around this time, the family began taking long trips to Mississippi in the summer months, where he learned about the history of his family and fell in love with Southern Black American culture.

White’s talent was recognized at an early age. In seventh grade, he was one of five hundred Chicago public school students to receive a scholarship from the James Raymond Nelson Fund to attend Saturday art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. Along with Eldzier Cortor (1916–2015) and Margaret Burroughs (1915–2010), White took classes at the Institute until his junior year of high school, receiving instruction from and attending lectures by notable artists such as Ivan Albright (1897–1983). In these years White also exhibited with the Art Crafts Guild, which counted Charles Sebree (1914–1985), Richard Wright (1908–1960), Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), and other luminaries of the Black Chicago Renaissance among its members.

Born the year before the Chicago Race Riots, White was exposed to racism throughout his childhood and adolescence. At age fourteen he read Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) which sparked a sense of pride and a passion for Black American history. This caused problems for him at school, as the teachers deemed him a troublemaker for questioning the school’s Eurocentric curriculum. In 1934 and 1935 he won scholarships to study art, but these funds were rescinded when the awarding institutions learned that he was Black. Finally, in 1937, White received—and was able to collect—a scholarship to attend the Art Institute of Chicago.

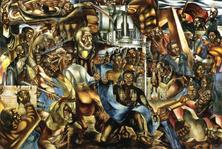

The following year, White joined the Works Progress Administration (WPA), first as an easel painter and then in the mural division. Despite the program’s racially discriminatory power structure, White was given the opportunity to create his first mural after less than a year. In late 1939, he completed Five Great American Negroes, a five-by-twelve-foot canvas depicting Marian Anderson, George Washington Carver, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Booker T. Washington. The following year he was commissioned by the Associated Negro Press (ANP) to create another mural, A History of the Negro Press, for the American Negro Exposition at the Chicago Coliseum. A selection of his works on paper was also included in the Exposition’s art show, Exhibition of the Art of the American Negro, 1851 to 1940, organized by Alain Locke. While in the WPA, White met and befriended photographer Gordon Parks (1912–2006), with whom he would often walk through Chicago’s South Side as they photographed and sketched daily life in the neighborhood.

The 1940s were eventful years for White. In 1941, he met and married artist Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012) and moved to New Orleans, taking a teaching position at Dillard University, where Catlett was chair of the art department. A Julius Rosenwald Fellowship awarded in 1942 enabled White to move to New York City to study at the Art Students League with Harry Sternberg. The fellowship also provided him the funds to travel throughout the South to research his next mural, The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America at the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Hampton, VA. With funding from an additional Rosenwald Fellowship awarded in 1943, White spent a year creating the mural. At Hampton, he met and befriended art professor Viktor Lowenfeld (1903–1960) and his student John Biggers (1924–2001). After returning to New York in 1944 to teach at the George Washington Carver School, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, serving as a corporal in the all-Black 132nd Engineering Regiment. He was honorably discharged eight months after contracting tuberculosis, a disease that would compromise his health for the rest of his life.

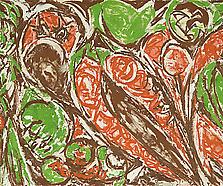

White was interested in Mexican mural painting, and in 1946 he and Catlett moved to Mexico City to join the famed graphic arts collective Taller de Gráfica Popular. White and Catlett returned to New York the following year to complete their divorce proceedings. That same year, The American Contemporary Art (ACA) Gallery in New York mounted White’s first solo exhibition, a series of works depicting the strength and beauty of real and archetypal Black American women. In 1948, White underwent several operations at Saint Anthony’s Hospital in Queens to treat his ongoing health issues before being transferred to a veteran’s hospital. Francis Barrett, a social worker he had met while teaching art at the Wo-Chi-Ca summer camp, was one of the few people who would dispel warnings about contracting tuberculosis and visited White regularly during his recuperation. Barrett was encouraged to visit by Margaret Burroughs, another counselor at Wo-Chi-Ca—short for Workers Children’s Camp—an interracial, coed camp founded in Hunterdon County, NJ, by the International Workers Order. Barrett and White married in 1950, initiating a new chapter in the artist’s life.

With the rise of McCarthyism after World War II, the FBI began a surveillance file on White. Although he never joined the Communist party, White's political inclinations and his friendships with leftist artists and intellectuals eventually led to his being called to testify at the hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Fortunately, and for mysterious reasons, he was later informed that his testimony was no longer needed. Undaunted, White continued to advance a politics of struggle in his art, executing ennobling portraits of historical figures and ordinary Black Americans that emphasized their grace and strength. White’s career flourished throughout the 1950s; his work entered the collections of several renowned institutions, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, which acquired Preacher (1952), and he received numerous awards, including a John Hay Whitney Foundation Opportunity Fellowship (1955–56). His first monograph, Charles White: Ein Künstler Amerikas by Sidney Finkelstein, was published by VEB Verlag der Kunst in 1955.

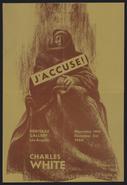

After spending two months bedridden with tuberculosis, White relocated to the warm, dry climate of southern California in 1956, where he and Barrett remained for the rest of their lives. He continued to create works that addressed the violence of racism and the heroism of those who stood up to it with such works as Southern News Late Edition (1961) and the J’Accuse series (1966). In 1965, he began teaching at the Otis Art Institute (now the Otis College of Art and Design) in Los Angeles, where he remained on the faculty and served as Chair of the Drawing Department until his death in 1979. Students who studied under him at Otis include David Hammons (b.1943), Suzanne Jackson (b.1944), and Kerry James Marshall (b.1955).

Throughout the 1970s, White remained committed to portraying the vibrancy, joy, and pain of Black American history and culture in his art. In 1970, he traveled to Belize to further his study of the history of enslavement and of the “maroon republics” founded by escaped enslaved people throughout Latin America. This experience intensified White’s interest in the nineteenth-century American posters for runaway slaves, and he used the funding he received from a Tamarind Fellowship to expand his celebrated Wanted Poster series, the print editions of which ran from 1969–72. In 1975, he was commissioned by the Johnson Publishing Company (the owner of Ebony magazine) to illustrate the landmark book The Shaping of Black America by Lerone Bennett, Jr. That same year, he was elected as a full member of the National Academy of Design, one of only three Black artists selected for inclusion at the time, along with Hughie Lee-Smith (1915–1999) and Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937). White returned to mural painting two years before his death with Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune at the Mary McLeod Bethune Public Library, in Los Angeles, CA—a fitting final masterpiece given the many hours he spent at the public libraries of Chicago as a child.

As art historian David Driskell writes, “White made positive portrayals of his people with symbols relevant to the harsh social and political climate of the time because he had experienced that climate as a black artist and knew firsthand how long change took in this nation, particularly in his lifetime.”[3] In 1979, White died of congestive heart failure. A year later, the town of Altadena, CA, dedicated Charles White Park in his memory. In the early 2000s, a school in MacArthur Park—on the former campus of the Otis Art Institute—was renamed Charles White Elementary, where the Los Angeles County Museum of Art maintains a satellite gallery. In 2021, through a gift from Board of Trustees Chair Mei-Lee Ney, the Otis College of Art and Design established the Charles White Art and Design Scholarship, a four-year, full-tuition undergraduate scholarship for two students, awarded yearly in perpetuity to uphold White’s legacy and honor his enduring influence at Otis.

Since its inception, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has championed the work of Charles White. The artist was a fixture of the gallery’s acclaimed annual exhibition series African-American Art: 20th Century Masterworks (1994–2003), and in 2009 the gallery mounted the acclaimed solo exhibition Charles White: Let the Light Enter. In 2018, the gallery showcased White’s art alongside the work of his artist friends and colleagues in Truth & Beauty: Charles White and His Circle. The gallery has exhibited White’s work in numerous group exhibitions including Embracing the Muse: African and African American Art (2004), RISING UP/UPRISING: Twentieth Century African American Art (2014), and Figuratively Speaking (2018).

White has consistently been featured in important group and solo exhibitions in recent years. Scholar, art historian, and curator Kellie Jones included White in her seminal historical survey Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980 at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, CA, which toured the country from 2011 to 2013. In 2018, a landmark touring retrospective co-organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and The Museum of Modern Art in New York, Charles White: A Retrospective opened at the Institute, traveling to MoMA and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through 2019. Curated by Sarah Kelly Oehler, the Institute’s Field-McCormick Chair and Curator of American Art, and Esther Adler, MoMA’s Associate Curator of Drawings and Prints, the exhibition was the first major retrospective of the artist’s work in over thirty years and drew widespread critical praise, generating a nationwide resurgence of interest in White’s oeuvre. In 2019, Charles White: Celebrating the Gordon Gift opened at the Blanton Museum of Art and the Christian-Green Gallery at The University of Texas at Austin. Two group exhibitions examining the enduring influence of White’s life and art, Plumb Line: Charles White and the Contemporary at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles and Life Model: Charles White and His Students at Charles White Elementary School also opened in 2019.

In 2020, White’s work was featured in several major historical group exhibitions including Tell Me Your Story: 100 Years of Storytelling in African American Art at Kunsthal KAde, Amersfoort, The Netherlands; the traveling exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, organized by Tate Modern, London; Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and Grace Before Jones: Camera, Disco, Studio at Nottingham Contemporary in the United Kingdom. In 2022–23, White’s work was prominently represented in From Posada to Isotype, from Kollwitz to Catlett at the Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain; Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; and the 35ª Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. In 2024, the Cincinnati Museum of Art mounted the career survey Charles White: A Little Higher.

White’s work can be found in numerous museums worldwide including the Amon Carter Museum of Art, Fort Worth, TX; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH; Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, ME; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX; Deutsche Akademie Der Kunst, Berlin, Germany; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA; Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, MI; Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA; Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, AL; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; National Academy of Design, New York, NY; National Center of Afro-American Artists, Boston, MA; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO; Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA; Oakland Museum of California, Oakland, CA; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ; The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia; Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO; SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, New York, NY; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; Taller de Gráfica Popular, Mexico City, Mexico; Tate Britain, London, UK; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; Wichita Museum of Art, Wichita, KS; and Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.

1. Charles White quoted in Andrea D. Barnwell, Charles White, The David C. Driskell Series of African American Art: Volume I (San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2002), 3.

2. Also known as: Charles Wilbert White, Charles W. White, Charles Wilbert White, Jr., Charles Wilbert White III, Charles White III

3. David C. Driskell, in Barnwell, Charles White, v.