Reception for the Artist: Thursday, April 28, 2022 / 6-8PM*

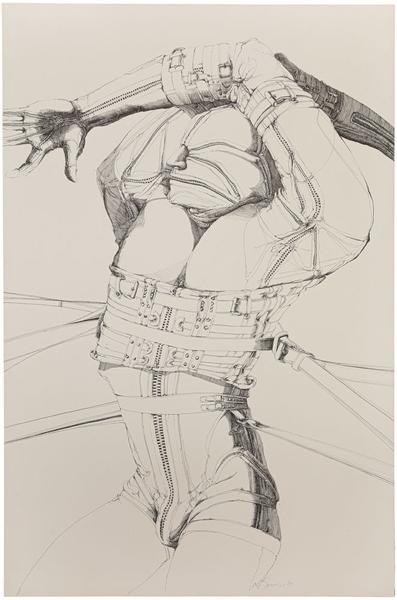

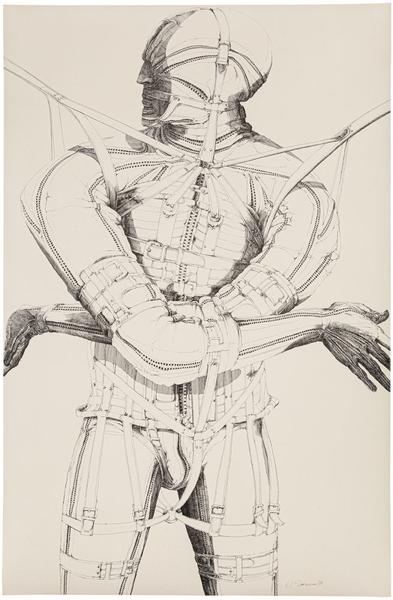

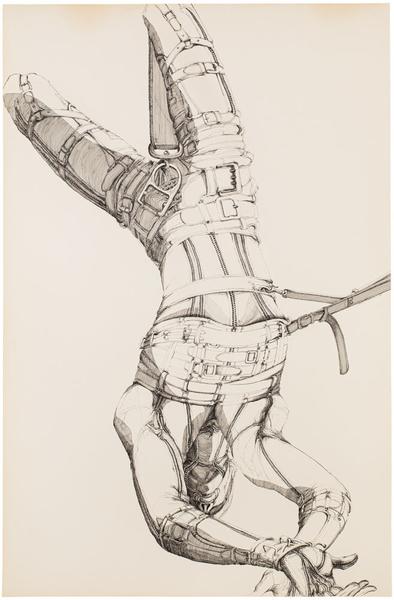

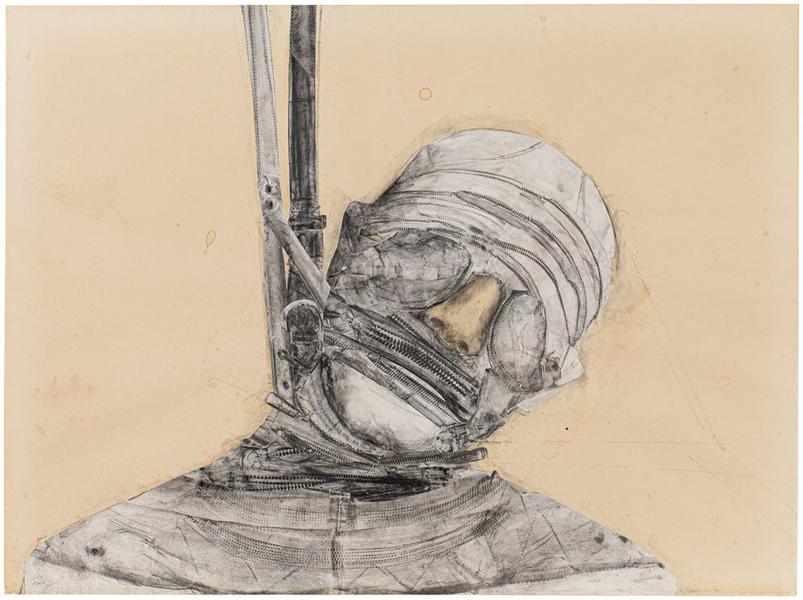

Grossman’s pieces come much closer to armor and prosthetic than to restraint and fetish…Nature gives us one face and we make ourselves another. Her horns, harnesses, zippers, straps, reins, and skins mark us as beasts but not animals…Strapped in, strapped on, we confront the massive brutality of the world’s misrecognitions.[1]

—Nayland Blake

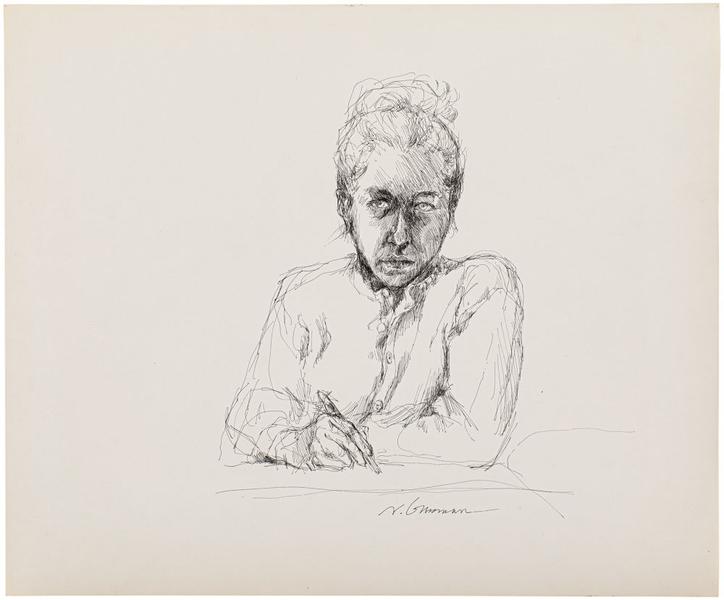

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery is pleased to announce its fifth solo exhibition featuring the work of Nancy Grossman (b.1940), which focuses on the artist’s oeuvre-spanning engagement with the figure in sculpture, collage, printmaking, painting, and drawing. Encompassing over five decades of her career, Nancy Grossman: My Body surveys the major developments in the artist’s treatment of the human form, which she conceives of as an arena in which the intricately related themes of agency, otherness, vulnerability, and identity play out in both collective and individual terms.

“The body of work which I’ve produced in the last thirty years may simply revolve around my own body,” Grossman wrote in 1991. “But then I may be, for all intents and purposes, a Heavenly body or the Wizard of Oz.”[2] Invoking the cosmic perspective in which her practice is grounded, Grossman describes a guiding principle of her early and middle career in this poetic statement, which conveys the immutable status the human form holds in her work. Using the body as a touchstone, Nancy Grossman: My Body showcases an interdisciplinary selection of works representative of the artist’s figural practice.

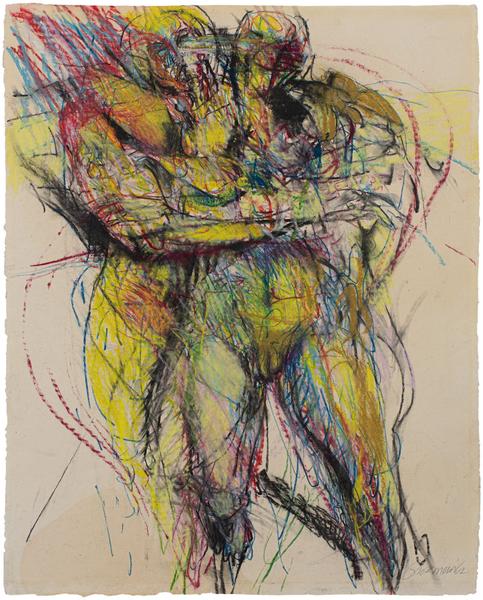

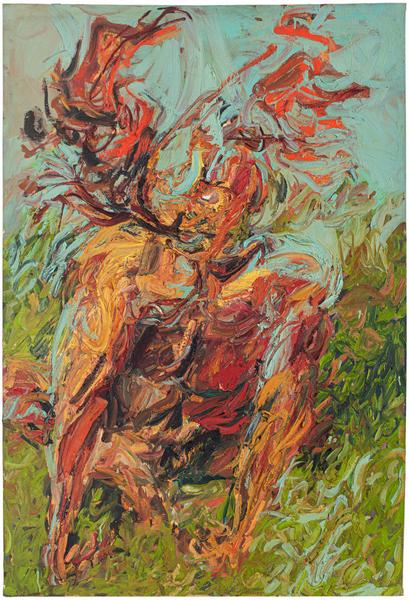

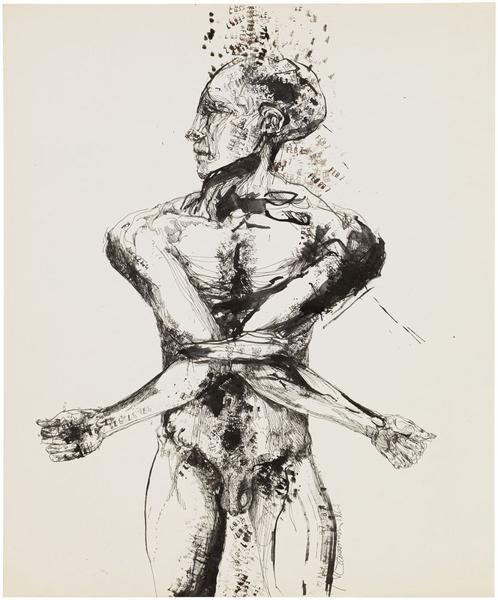

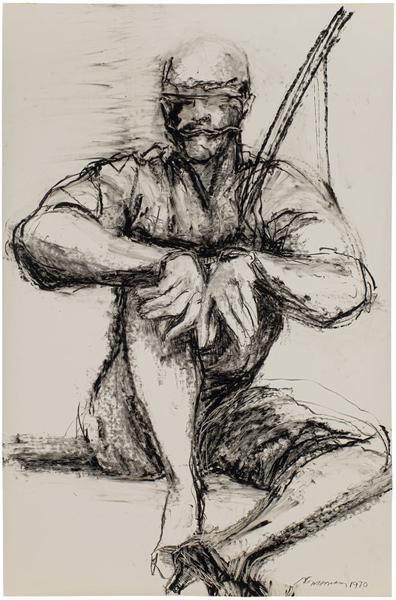

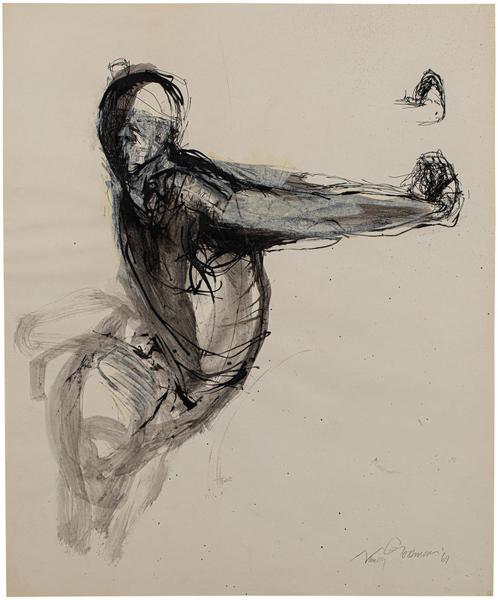

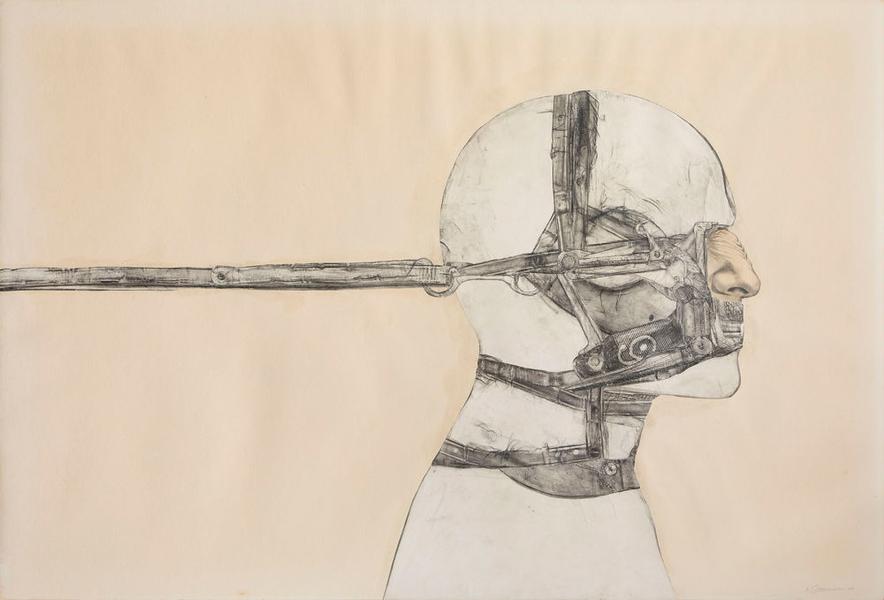

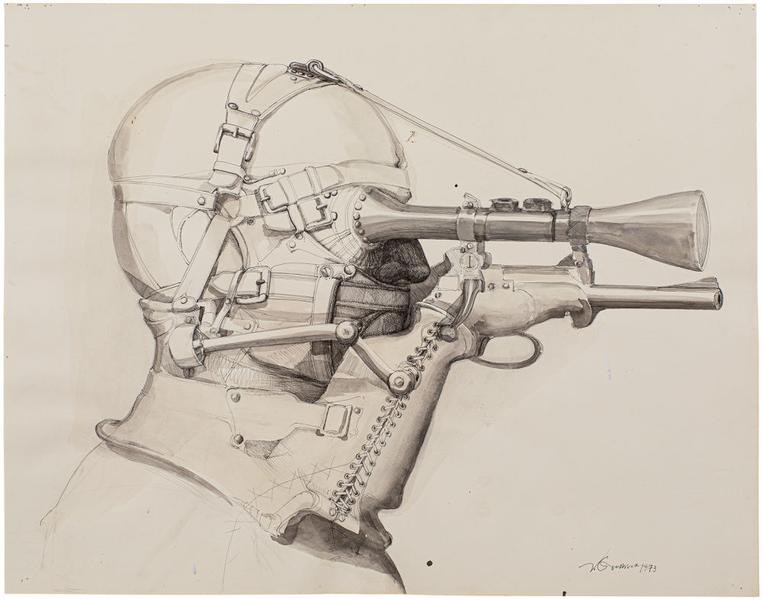

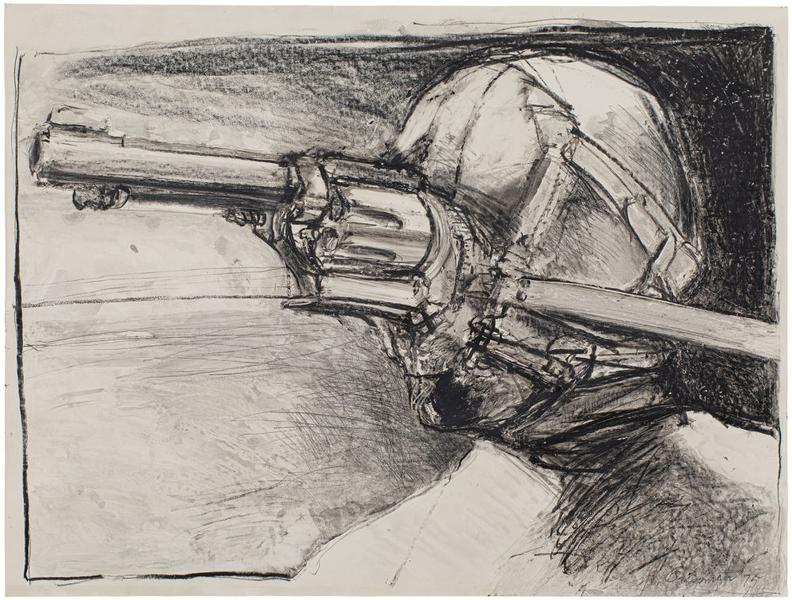

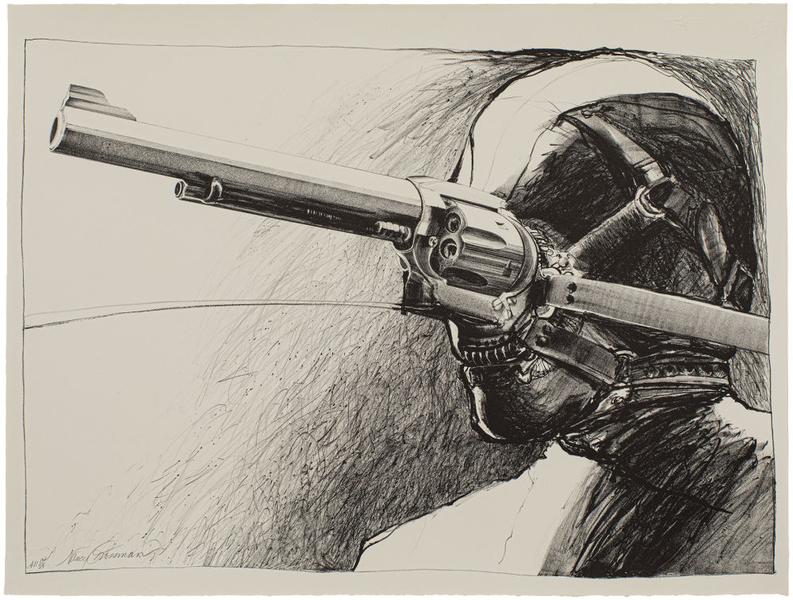

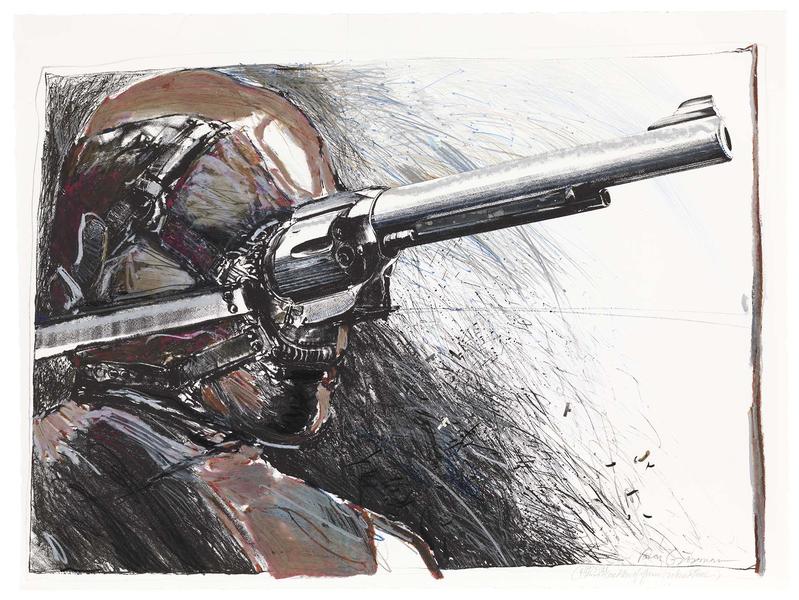

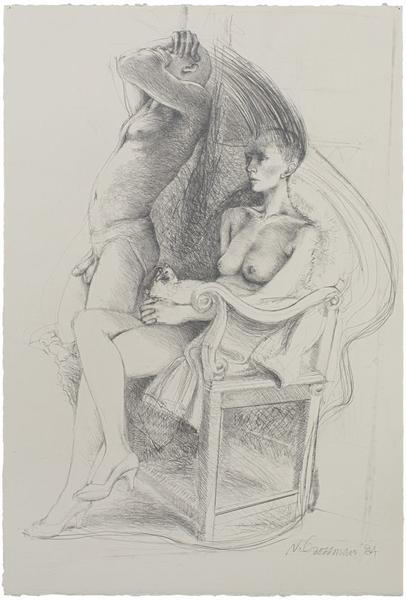

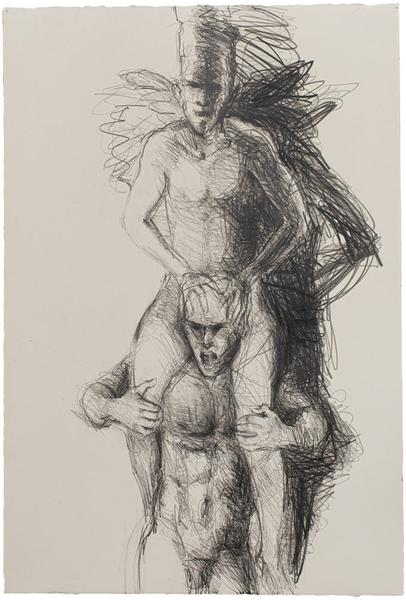

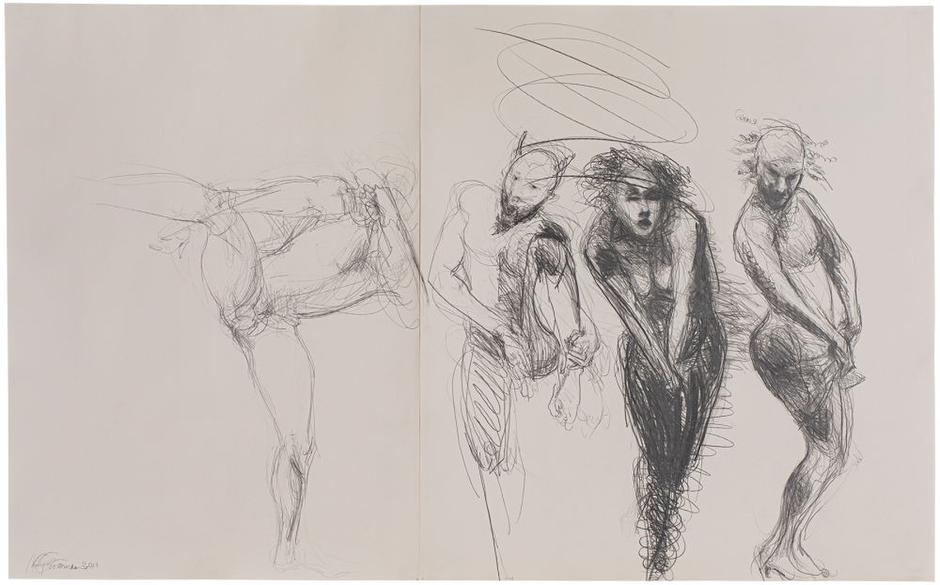

Demonstrating the longevity of the artist’s interest in the figure, Grossman’s early oil and pastel works render the body as entangled masses of expressionistic brushstrokes radiating outward in a perpetual state of disintegration, merging figure and ground in varying degrees of legibility. The artist created her earliest drawings of bound figures struggling against their tethers in these years as well, anticipating the theme of bodily compromise that would undergird much of her output in the following decades. As art historian Arlene Raven observes: “[Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818)] is a tale of awakening female sexuality with feminist and humanist underpinnings…As well, it is an early—although hidden—narrative about the ‘female as other.’ The novel on which so many macabre films are based is also one of the most poignant descriptions of (self) creating monstrosity. Monstrosity has been a designated trait of nondominant peoples throughout history and a culturally-enforced psychological self-image for unruly women.”[3]

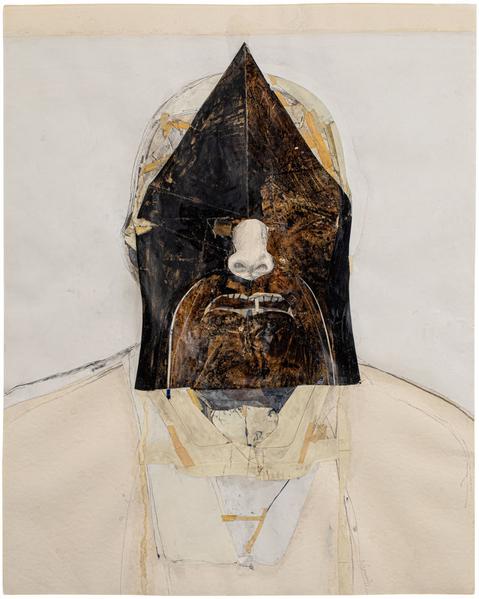

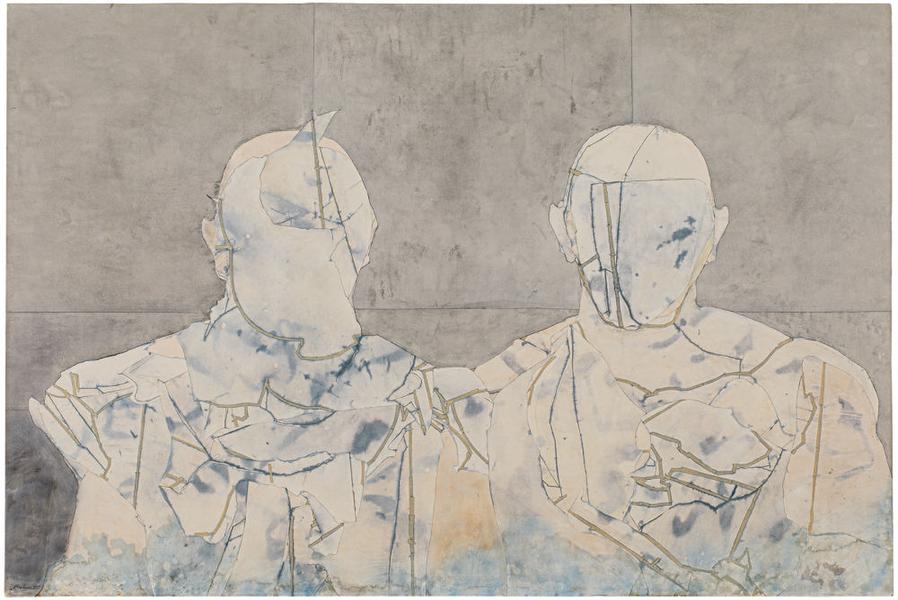

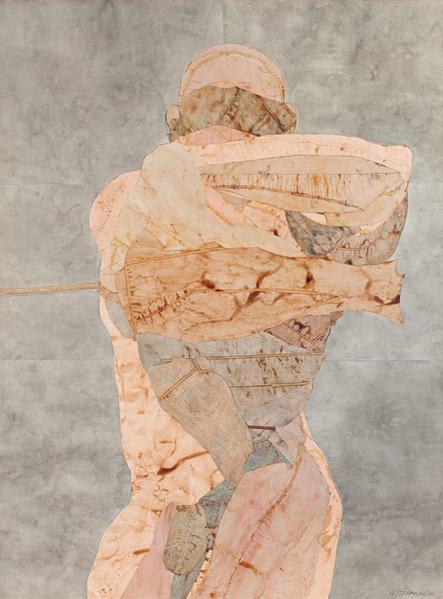

Shelley’s monster is indeed a useful allegory for looking at Grossman’s work, not only in terms of the social constructs she often addresses, but also when considering her formal approach; collage has been a vital aspect of the artist’s practice since 1962. Accordingly, My Body exhibits examples of Grossman’s series of dyed paper collages from the 1970s, which depict men of herculean proportions in various positions of restraint. Grossman discovered that soaking paper cut-outs in water and dye, letting them dry, and repeating the process imbued the material with a weathered texture that resembles skin, especially when organized in a schema reminiscent of human musculature. Held in place by suture-like lines of masking tape and streaked with stains resembling bruises and veins, these collages render their subjects as powerfully brawny yet helpless amalgamations of flesh.

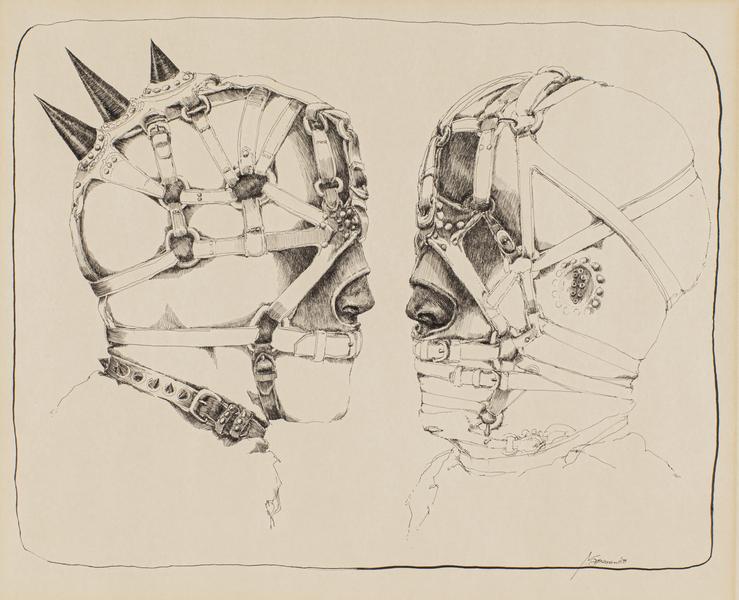

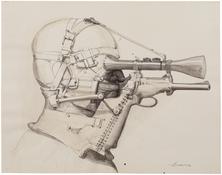

While much of Grossman’s work deals with the strictures and inadequacies of gender constructs, the artist comes at the subject obliquely, using her own unique set of symbols and metaphors: “Whenever I wanted to say something specific, personal…I would use a woman’s image,” she explains. “But if I wanted to say something in general, I would use a man. It’s as if man was our society. Yet I don’t feel I have to conform to a political identification although, naturally, I’m a feminist. But if we have to split hairs, I’m a humanist.”[4] This approach allows for a layered reading of Grossman’s figural works, permitting her subjects to be read variously as stand-ins for the viewer, the artist herself, or society as a whole. The figures in her work are often manifestations of an interior identity, emotional state, or collective ethos the artist seeks to express in bodily terms. In the case of her celebrated series of leather-covered heads begun in the late 1960s, the artist considers these sculptures to be self-portraits, as she conceived of them at a time in her life when she felt isolated and vulnerable. Constructed from a wooden base over which she often applies epoxy, invented eyes, teeth, horns, and other accoutrements, these sculptures invoke the barriers the individual creates to protect themselves from society’s conflicts, which, in turn, limits their capacity for self-expression.